Arguably, the book can be a testament to what Dr. Kenneth Atchity calls “Dealing with Type C Minds” – C for Creative and C for Crazy. Dr. Kenneth Atchity writes about psychology of creativity: he divides creative productive people into two domains, happy and unhappy. Happy are the ones that know the curve ball a creative process throws: that after completion of one project, the doer is destined to fall into depression like a mother who goes into postpartum depression after that being is out of her womb. In fact, heavily productive people know that this digression into depression will happen, so they keep a steady supply of projects. They happily finish one to get into another and avoid the blues. Unhappy productive people are baffled by the psychology of creativity. This is the reason why you see writers like Ernest Hemingway, Sylvia Plath and Virginia Woolf finding themselves there in the end.

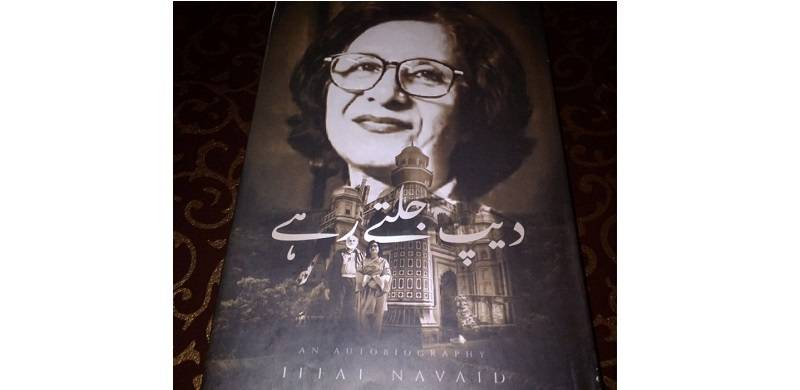

I was mentioning this in a video interview that I gave for Lahore International London along with my pledge writers to end stigmatisation of diseases like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Listening to this, Mr. Tariq Rahman, Director of Fazleesons Publishing who also honoured me by publishing my first novel, send me several books to quench my creative thirst. One of them was an autobiography by writer Iffat Navaid, mainly revolving around her poet husband Mir Ahmed Navaid making a name in the Subcontinent like his ancestor poet Mir Anees.

This autobiography is a living embodiment of accepting a life entangled with the psychology of creativity, and dealing with a psychologically ungifted but more creative person. She opens up quite beautifully yet articulately how she spent her life with a poet affected by Plath affect.

Her first encounter with her husband's episode was of disbelief, and the display of naivete was from her end. When his parents and siblings told her that her husband is sinking down into his schizophrenia, she was a little apprehensive. But things went out of her hands, and her husband's condition worsened so much then she had to run to admit him to the hospital. Soon afterwards, she saw a vehicle intended to transport hardcore criminals taking her husband away, who only lost the status of having a sane mind –with no fault of his own, purely down to fate.

And when she went to see her husband, the receptionist told her that her husband wouldn't be spared of his wrongdoings. He looked at the writer, winked and let out a wicked laugh. Now her husband, being agitated, was whisked away by two strong men and into the general ward of the mental hospital. She was told there can’t be any home-cooked food or visits for the first four days.

Disillusioned by the system, she got him discharged, and went for personal monthly administration of injections. Her life story is chaptered into her husband's monthly injection deadline. Lose that deadline and lose your beloved falling into an abyss and losing the only thread that a relationship survive on –communication.

It wasn't the lack of metaphysical connection, but a physicality as well. She had to endure whenever her husband start sinking into his schizophrenia. Iffat Navaid is a survivor and a hero; standing above all in empathy and taking care of a person many would not sign up for. And most importantly, she helped her beloved not only survive and sustain, but succeed. Mir Navaid is today one of the recognised poetic voices of the Subcontinent. His progress only shone through because Iffat Navaid didn’t give up.

Another chapter of her life that starts with the whooshing sound of her husband’s injection deadline is about how Modicat injection was in short supply in the market, so their psychiatrist recommended some other (I really wish she would have named the injection). Habitually reading the cautionary notes on the bottle, she remembers the phrase that one in a thousand might feel adverse effects like tongue convulsions, trembling legs and high fever.

She writes that the probability of being affected by the injection was one in a thousand, and even with years passing by, that thought does not leave her mind.

Fast forward to when her boys took the responsibility for the monthly dose of injection. Their father convinced them that those injections are just a hoax and part of their mother's wicked ways. Several months passed by and not only their mother but a lot of other people also noticed his condition. He had shaved his head, wore one earring and in his quest to look sane, exuded insanity.

Iffat Navaid’s book is a work of courage; she opened up despite people piling shame on her as to why she wrote about Mir Navaid’s mind in this candid way. She survived valiantly – moving through rented homes, being the actual breadwinner and fighting many demons in marital bliss and sectarian harmony, for a span of three decades. But she stayed true to her first love –the research officer at the Karachi office of the National Book Council, Pakistan.

She fell in love thirty years ago. Iffat Navaid’s autobiography is the “True Love” of David Whyte:

There is a faith in loving fiercely

the one who is rightfully yours,

especially if you have

waited years and especially

if part of you never believed

you could deserve this

loved and beckoning hand

held out to you this way.

I am thinking of faith now

and the testaments of loneliness

and what we feel we are

worthy of in this world.

Years ago in the Hebrides,

I remember an old man

who walked every morning

on the grey stones

to the shore of baying seals,

who would press his hat

to his chest in the blustering

salt wind and say his prayer

to the turbulent Jesus

hidden in the water,

and I think of the story

of the storm and everyone

waking and seeing

the distant

yet familiar figure

far across the water

calling to them

and how we are all

preparing for that

abrupt waking,

and that calling,

and that moment

we have to say yes,

except it will

not come so grandly

so Biblically

but more subtly

and intimately in the face

of the one you know

you have to love

so that when

we finally step out of the boat

toward them, we find

everything holds

us, and everything confirms

our courage, and if you wanted

to drown you could,

but you don’t

because finally

after all this struggle

and all these years

you simply don’t want to

any more

you’ve simply had enough

of drowning

and you want to live and you

want to love and you will

walk across any territory

and any darkness

however fluid and however

dangerous to take the

one hand you know

belongs in yours.