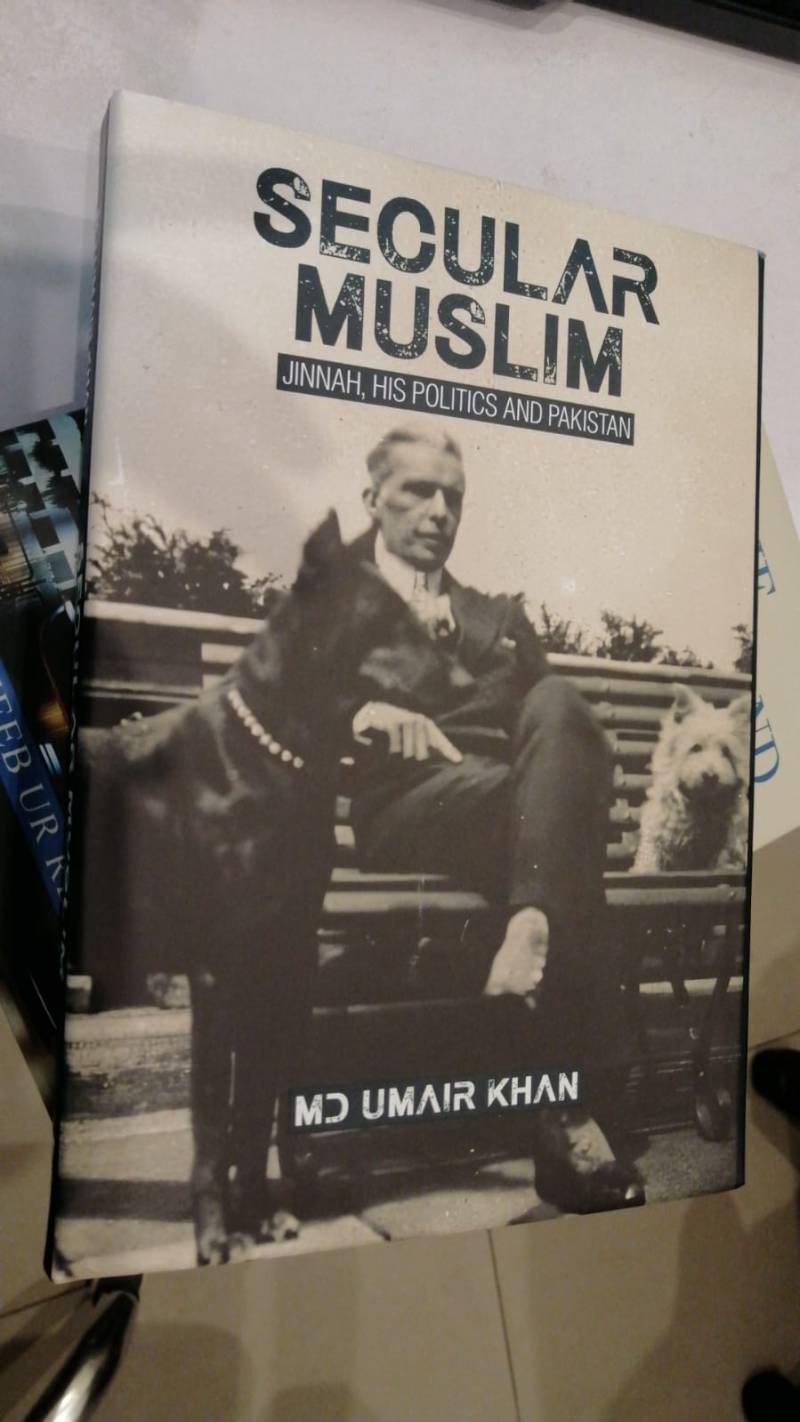

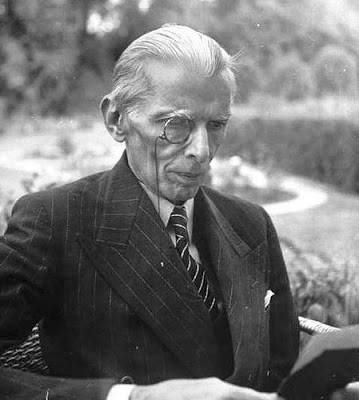

Secular Muslim: Jinnah, His Politics, and Pakistan, authored by MD Umair Khan and published by Vanguard, is a commendable addition to the growing body of literature centred on Mr Jinnah. In a time when discussions around his vision have intensified, Khan's book emerges as a valuable contribution. Addressing the narrow and myopic narrative of the state since the 1980s, which seeks to reshape Jinnah's legacy into that of a votary of an exclusivist Islamic state, the book unveils the multifaceted dimensions of the man's life and ideology.

Written by a young, self-taught historian, the book is a treasure trove of primary source material and makes the following points boldly and with compelling clarity:

Origins of the Two-Nation Theory

The book dispels the notion that the Two-Nation theory solely originated from the Muslim community. Khan adeptly illustrates how Hindu reformers, ideologues, and politicians had already introduced this concept, and he points to the Partition demand being initially made by notable Congress leader and freedom fighter Lala Lajpat Rai.

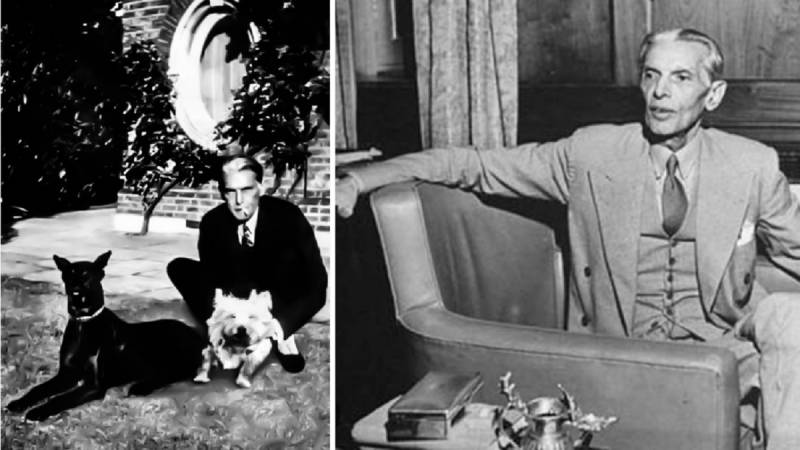

Jinnah's Liberal Roots

Khan underscores Jinnah's education in the currents of English liberalism prevalent in the late 19th century during his time in London. This upbringing fostered Jinnah's commitment to religious liberty and equality for all, irrespective of identity be it creed, caste or race. The book highlights Jinnah's work as an Indian nationalist who championed Hindu Muslim unity, earning him the moniker "Best Ambassador of Hindu-Muslim Unity."

Religion in Politics

The book rightly identifies Gandhi as the one who infused religion into Indian politics. Congress' Hindu-majoritarian stance drove a wedge between Jinnah and the party. Yet, even as a member of the Muslim League, Jinnah remained dedicated to a united India until around 1946. The Congress' inflexible approach to the communal problem obstructed Jinnah's attempts at cooperation and unity.

Understanding the Demand for Pakistan

The book delves into the nuanced interpretation of Jinnah's demand for Pakistan, revealing that it originally aimed at establishing autonomous regions within an Indian federation. The concept did not inherently entail the division of the subcontinent or its provinces.

Opposition of the religious parties

The book sheds light on the trenchant opposition to Jinnah and the Pakistan demand by the religio-political parties like Jamiat-e-Ulema Hind and Majlis-e-Ahrar, who attacked Jinnah for being too secular and a liberal. Majlis-e-Ahrar-e-Islam called Jinnah Kafir-e-Azam because Jinnah refused to accede to their demand about expelling the Ahmadis from the Muslim League.

Partition of Punjab and Bengal

Khan highlights how the decision to partition Punjab and Bengal was orchestrated by Congress in the respective provincial legislatures. Jinnah consistently opposed this partition and argued that provinces as a whole should choose one federation or the other.

Jinnah's Vision of a Secular State

The book extensively examines Jinnah's idea of a secular state, where religion would be a personal matter and not the business of the state. Jinnah's commitment to Muslim modernist school of thought contextualizes his references to Islamic principles – these references were intended to bolster the case for a secular state, rather than to oppose it. As a politician, Jinnah had to convince his constituents that a secular democratic state was not in conflict with Islam.

Oaths of office

The book sheds light on Jinnah's omission of references to God from official oaths. This crucial omission underscored his commitment to a Pakistan that treated believers and non-believers equally.

In an era where discussions on Partition frequently revolve around assigning blame for the ensuing violence, Khan's book challenges the conventional Indian narrative that lays responsibility on Jinnah's shoulders. "Secular Muslim: Jinnah, His Politics, and Pakistan" presents an important alternative perspective, shedding light on the complexities and nuances that surrounded this pivotal historical period.

History is often litigated and re-litigated around the world. This is why the question of founding vision is debated in many countries. For Pakistan it is an existential question: Was Pakistan created in the name of Islam? The book’s answer is a resounding and an unequivocal no. As Khan shows, Jinnah explicitly ruled out the idea of a theocracy in Pakistan and reiterated its commitment to secular democracy. Khan’s effort therefore is substantial. He has separated the chaff from the grain and his work will go a long way in clearing the cobwebs around the true ideology of Pakistan, which is of a modern and progressive nation state committed to the highest ideals of human conduct. Present day Pakistan has failed to live up to that ideal and instead has adopted a faux ideology – now incorporated in the theocratic constitution of Pakistan as well. This is why the work under review is of great importance to Pakistan’s future because the theocracy it is today can never work in the long run. Ultimately Pakistan will have to hark back to Jinnah’s secular vision and modernist Islam to succeed.