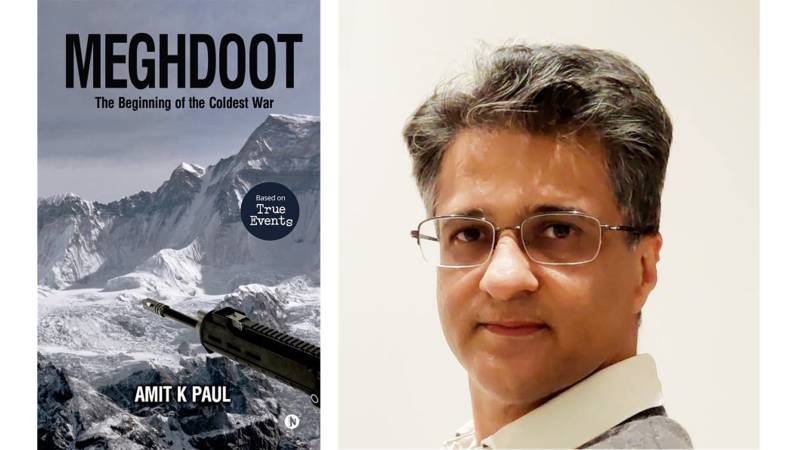

One of the most bizarre armed conflicts of contemporary times has been fought between India and Pakistan at the prohibitive heights of the Siachen Glacier in the Karakoram Range where temperatures dip to minus 40 degrees centigrade and lower. While several books and papers have been written on this subject, Amit K Paul’s Meghdoot presents India and Pakistan’s competing arguments in a very interesting and engaging manner.

Basing himself on seminal research from Indian, Pakistani, US and UN source materials and a study of almost all other published sources, the author strings together all the facts chronologically in a taut narrative which enables the reader to easily comprehend the issues and also visualize the action as it unfolds. He adds a fictional dimension to the book by imagining what the discussions would have looked like as real characters on both the Indian and Pakistani sides discuss and debate different aspects of the Siachen standoff.

Operation Meghdoot (Cloud Messenger) was launched on 13 April 1984 by the Indian Army to preempt Pakistan from establishing its presence on Siachen. The author notes that it “is perhaps the costliest and longest ongoing military operation of the Indian Army.” As far as one knows, except for unending layers of snow and ice, impossible trekking challenges and wilderness, Siachen and other glaciers have nothing else to offer – and yet this impasse continues. Meghdoot meticulously examines why and how this confrontation started.

While territorial ambiguity has notoriously been the root cause of armed conflicts including major wars between nations down the centuries, the author contends that despite historical differences on Kashmir, as far as Siachen is concerned both the countries had a clear and unambiguous written understanding which ensured peace in the region despite conflicts in 1965 and 1971.

After the first war on Kashmir in 1947, a UN mediated ceasefire came into effect on 01 January 1949. Thereafter, military commanders from both sides clearly delimited the working boundary between India and Pakistan on 29 July 1949 when the Karachi Ceasefire Agreement was signed. The demarcation of the boundary as per this Agreement commenced thereafter but instead of being completed as per its mandate was stopped abruptly at a point (NJ 9842) as beyond it lay a large mass of inaccessible glaciers.

The author underscores that as per Clause B2d and C of that agreement, the ceasefire line was to proceed “thence north to the glaciers” and be demarcated in a manner “so as not to leave any no man’s land.” He quotes the demarcation document executed subsequently stating that the boundary moves “thence northwards along the boundary line going through Point 18402 up to NJ 9842” and contends that if at all the line had to be extended beyond this point it should have been done mutually by the parties following the directive of the Agreement by proceeding North, in which case a bulk of this region would have come to India.

In September 1968 Geographer Robert D Hodgson, Chief Cartographer of the US State Department, in response to the US Ambassador in India wanting to get clarity on the depiction of India’s boundaries in Jammu and Kashmir on US maps, decided that the boundary between India and Pakistan in that State could not be left hanging in the air at NJ 9842. Perhaps, taking cognition of the fact that Pakistan was a US ally and member of SEATO and CENTO he decided that the ceasefire line instead of terminating at NJ 9842, should move in an easterly direction “till the Karakorum Pass from its current position so that all States are closed off.” This meant that the Siachen Glacier was allocated to Pakistan.

This brilliant study of the Siachen conflict ends with the author subtly observing that the coldest war has cost both the countries in men as well as resources

This line drawn by Hodgson was neither the line agreed to by India and Pakistan in the Karachi Agreement nor an international border. Following the 1971 war between India and Pakistan, the Simla Agreement of July 1972 signed by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto altered the Ceasefire Line slightly because both sides had captured each other’s territory. Hence this new line was now called the Line of Control. However, this line too terminated at NJ 9842 and this Agreement did not deal with the region beyond it.

Under the circumstances, Pakistan began to grant foreign hikers permission to explore the glacier. That trend gained momentum from early 1980 onwards and made the Indians suspicious. Equally, the Pakistanis noted that India too was active on the glacier. However, Pakistan’s protest notes of 1983 claiming the region defined by Hodgson’s line as its own set the alarm bells ringing in India – and around September 1983 patrols from both sides came face-to-face on the glacier. Pakistan, in fact, occupied the glacier for about 10 days at that time but its troops had to return due to the inclement weather and lack of proper equipment.

After this encounter, discussions started on both sides to pre-empt the adversary from establishing a firm hold on Siachen. On the Pakistani side, in a meeting in December 1983 (confirmed by Lt Gen Jahan Dad Khan in his book) presided by Gen Zia-ul-Haq it was decided to establish a firm presence on Siachen, but in May, when the weather is less severe. When the Indian intelligence got wind of the Pakistani plans, a series of meetings took place on the Indian side and Operation Meghdoot was planned. Presently India controls the Saltoro heights and hence the Glacier, while Pakistan controls the lower western slopes of the Saltoro.

This brilliant study of the Siachen conflict ends with the author subtly observing that the coldest war has cost both the countries in men as well as resources. He remarks, “Both Indian and Pakistani soldiers continue to do their duty on either side of the Saltoro and hope that one day their governments will be able to resolve the dispute amicably.”

The greatest strength of this short but very engaging book is that the author writes with impartiality, which few authors can maintain when dealing with contentious issues dividing nations and while doing so clears several misconceptions prevalent about this dispute.