After five years of a sustained political visibility of women, there has been a new dawn of industrialist politicians venting it out on our TV screens. Where are the Kashmalas and Firdauses, who were first mocked, and then liked, until eventually the inherent Pakistani misogyny bowed down, accepting them as serious political contenders? Since the departure of the Pakistan People’s Party, female political visibility has dropped significantly (save Maryam Nawaz Sharif’s cursory media appearances that are not substantial), ending the most crucial of all discourses which was still in its infancy – that political progress can never be made if the suppressed voices of 51% of the population aren’t heard. And now, with peace talks with the Taliban underway, it is even more crucial that those voices are heard.

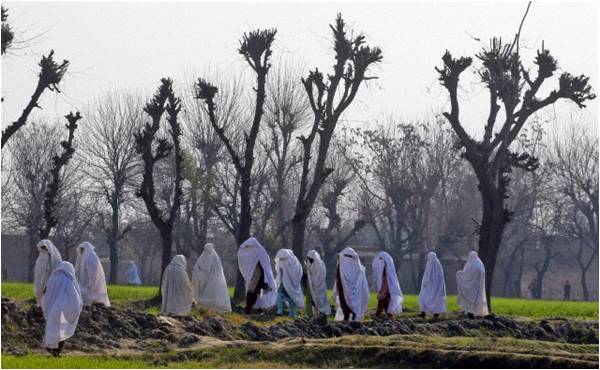

As we stand ready to bargain the lives and rights of 18 million Pakistanis under the euphemistic title of ‘dialogue’, the realization that certain segments of our population will be affected more than others is necessary. To what extent will we further Islamize an already semi-theocratic state, or to what degree can we ideally push back the militant horde via dialogue, only time will tell. But the answers to these questions will affect women more than men. The notorious anti-women practices of the Taliban in the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan were no secret. Mullah Fazlullah kicked off his campaign on a radio channel in Swat, speaking about women – how they are inferior to men in Islam. He spoke against women’s education and employment. The idea of a female political representative seemed out of question to his men, and the Parliament haram. Now that he heads the Pakistani Taliban, his first and foremost condition for a truce was the imposition of Sharia. And their interpretation of Sharia is notorious for being obsessed with control over a woman’s body – reproductive organs, face, skin, eyes and most recently even fingernails.

[quote]How much of their very little freedom are they willing to give up for peace with the Taliban?[/quote]

With such high stakes in this dialogue process, why have women not been made a part of it? What do they have to say about it, and how much of their very little freedom are they willing to give up for peace with the Taliban?

There has recently been a major focus on mainstreaming women in conflict-resolution and peace-building. This has been done by including them physically in the process, developing a consensus on what points regarding women’s rights are not to be compromised on, managing a sustained media campaign about the irrevocability of their basic human rights, and a strong grassroots mobility of women themselves.

But in Pakistan, women are absent from the process both physically and ideologically. Dastarkhwan discussions in Pakistani homes will seldom have women speak up between men as they talk about the “truth” of terrorism. They either don’t see the dagger coming at them, or they have been sidelined. Ironically, the women who did have a voice and should have taken the front have also gone quiet.

[quote]It is not a systematic disenfranchisement, it just represents our national culture[/quote]

Gulalai Ismail, founder of Aware Girls and one of the major civil society activists in leading the conflict resolution and anti-Talibanization movements in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA, thinks it is a reflection of our social values. She says the absence of women from the dialogue is not a systematic disenfranchisement. It represents our national culture, where in the time of “big issues” the decision making is considered a man’s duty, while the women prepare tea for them.

Senator Nasrin Jalil of the MQM presented a resolution in the Senate saying there should be no compromise on women’s rights during the dialogue. But that may not be enough.

In 2009, when the ANP-led Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government spoke to the Taliban, their negotiators came to Peshawar to meet the entire cabinet, including the minister Sitara Ayaz. In 2014, an all-male committee that includes no parliamentarians is meeting the friends of the Taliban in secret locations. That is how far we have fallen.

Just having started to take baby steps towards democracy, it remains to be seen how long it will take for us to realize the importance of representation of women.

As we stand ready to bargain the lives and rights of 18 million Pakistanis under the euphemistic title of ‘dialogue’, the realization that certain segments of our population will be affected more than others is necessary. To what extent will we further Islamize an already semi-theocratic state, or to what degree can we ideally push back the militant horde via dialogue, only time will tell. But the answers to these questions will affect women more than men. The notorious anti-women practices of the Taliban in the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan were no secret. Mullah Fazlullah kicked off his campaign on a radio channel in Swat, speaking about women – how they are inferior to men in Islam. He spoke against women’s education and employment. The idea of a female political representative seemed out of question to his men, and the Parliament haram. Now that he heads the Pakistani Taliban, his first and foremost condition for a truce was the imposition of Sharia. And their interpretation of Sharia is notorious for being obsessed with control over a woman’s body – reproductive organs, face, skin, eyes and most recently even fingernails.

[quote]How much of their very little freedom are they willing to give up for peace with the Taliban?[/quote]

With such high stakes in this dialogue process, why have women not been made a part of it? What do they have to say about it, and how much of their very little freedom are they willing to give up for peace with the Taliban?

There has recently been a major focus on mainstreaming women in conflict-resolution and peace-building. This has been done by including them physically in the process, developing a consensus on what points regarding women’s rights are not to be compromised on, managing a sustained media campaign about the irrevocability of their basic human rights, and a strong grassroots mobility of women themselves.

But in Pakistan, women are absent from the process both physically and ideologically. Dastarkhwan discussions in Pakistani homes will seldom have women speak up between men as they talk about the “truth” of terrorism. They either don’t see the dagger coming at them, or they have been sidelined. Ironically, the women who did have a voice and should have taken the front have also gone quiet.

[quote]It is not a systematic disenfranchisement, it just represents our national culture[/quote]

Gulalai Ismail, founder of Aware Girls and one of the major civil society activists in leading the conflict resolution and anti-Talibanization movements in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA, thinks it is a reflection of our social values. She says the absence of women from the dialogue is not a systematic disenfranchisement. It represents our national culture, where in the time of “big issues” the decision making is considered a man’s duty, while the women prepare tea for them.

Senator Nasrin Jalil of the MQM presented a resolution in the Senate saying there should be no compromise on women’s rights during the dialogue. But that may not be enough.

In 2009, when the ANP-led Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government spoke to the Taliban, their negotiators came to Peshawar to meet the entire cabinet, including the minister Sitara Ayaz. In 2014, an all-male committee that includes no parliamentarians is meeting the friends of the Taliban in secret locations. That is how far we have fallen.

Just having started to take baby steps towards democracy, it remains to be seen how long it will take for us to realize the importance of representation of women.