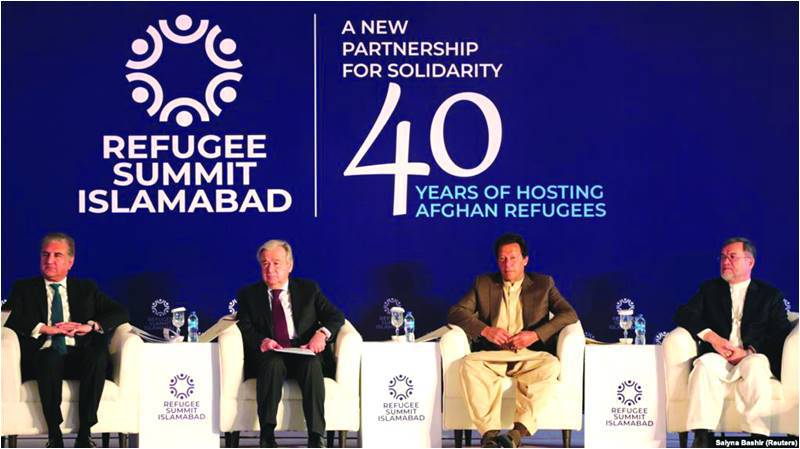

At the international conference on Monday in Islamabad on 40 years of Afghan refugees in Pakistan, United Nations (UN) Secretary General Antonio Guterres and UN High Commissioner for Refugees urged the world to refocus attention for ending the Afghan conflict and creating enabling conditions for repatriation and reintegration of refugees in Afghanistan. “We need a renewed commitment. Afghanistan and its people cannot be abandoned,” he said.

Attended by representatives of 20 countries, the conference took place at a time when peace talks between the United States and the Afghan Taliban have made some progress, with the latter agreeing to demonstrate their will and capacity to reduce violence in Afghanistan, even if it is temporary. Successful reduction in violence will be followed by intra-Afghan dialogue and phased withdrawal of US troops.

Recalling that millions of Afghans were given refuge for four decades without much international support, praise was rightly showered on Islamabad. The conference reminded that during the peak of the conflict, Afghan refugees in Pakistan numbered nearly 4.5 million. Although many have returned home, over 2.5 million still remain in Pakistan.

Prime Minister Imran Khan used the occasion to reiterate that Pakistan was keen on peace in Afghanistan at least for the sake of trade and connectivity and that talk of Pakistan of providing safe heavens to militants was rubbish. “Violence in Afghanistan was not in Pakistan’s interest,” he declared, repeating a narrative that has long been used to arouse conviction with the world. By declaring “there is a consensus within Pakistan for peace in Afghanistan,” the prime minister also unwittingly referred to divergent perceptions within state institutions on how to bring about peace in Afghanistan.

The foreign minister spoke about a seven-point action plan for activating the recently established ‘Afghan Refugees Support Platform’ that calls for, among other things, supporting the Afghan peace process, resettlement opportunities for refugees in third countries and creating an international fund for their return home.

But most of what was said in the conference was self-congratulatory. The conference, marking 40 years of Pakistan hosting the world’s largest refugee population, was an occasion for breaking fresh ground on refugee as well as peace in Afghanistan. Unfortunately that was not to be.

Neither the prime minister nor anyone else spoke about the most important initiative about refugees announced by him over a year ago: giving citizenship to Afghan children born in Pakistan. No mention was made of the UN Conventions on Refugees or Convention on Statelessness which Pakistan has steadfastly refused to sign.

There also was no word on need for national legislation on refugees and internally displaced people (IDPs) as a result of military operations in erstwhile tribal districts. There is no data available on children in refugee camps facing statelessness or of other vital areas of concern about refugees and IDPs. The conference ignored these trivialities. When the fact finding missions of bodies like the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan are not allowed to visit camps for internally displaced people, what is the value of data collection?

However, much was made of the newly drawn up seven-point action plan to address refugees’ issues. It drew applause also. But the far-reaching refugee management policy approved in February 2017 was ignored because that could have drawn applause for political adversaries. That policy called for adopting national legislation on refugees and declaring proof of residence (PoR) card for Afghan refugees valid till domestic legislation on refugees was enacted - issues about which the seven-point action plan is silent. The IDPs have been renamed as temporarily displaced persons (TDPs) to avoid making national legislation, so strong is our aversion to domestic legislation.

But peace in Afghanistan will not be restored by the seven-point action plan nor will it result in the repatriation of Afghan refugees. It will be restored only by revisiting the Afghan policy. The unwritten state policy to have a fragmented Afghanistan with a weak Pakistan-installed government that is not too friendly towards India lies at the root of the problem. Our current Afghan policy is based on a zero-sum game with India. The exaggerated Indian threat is designed to create justification for Taliban. Unless this policy changes, words alone that “peace in Afghanistan is peace in Pakistan” will not be sufficient.

It was the result of this policy that explains the prime minister’s remarks early last year that the current Afghan government was a hurdle to peace in Afghanistan. This policy is not new but age old. Remember in the 1980s Pakistan insisted that the Peoples’ Democratic Party (PDPA) government in Afghanistan be replaced with a neutral government.

Remember also that at the time we refused to talk directly with the Kabul government and UN special envoy Diego Cardovez shuttled between Kabul and Islamabad carrying messages to and fro. When finally talks did take place in Geneva, they were called “proximity talks” where Cardovez ridiculously shuttled from room-to-room because we did not want direct talks with a government in Kabul that we did not like. These proximity talks led to Soviet withdrawal but also resulted in civil war and endless bloodshed. PM Imran Khan may have gloated at the conference that Pakistan has delivered Taliban to negotiating table, but negotiations a la ‘proximity’ talks without all Afghan factions, including the current Kabul government, is fraught with the danger of ending in chaos.

The writer is a former senator

Attended by representatives of 20 countries, the conference took place at a time when peace talks between the United States and the Afghan Taliban have made some progress, with the latter agreeing to demonstrate their will and capacity to reduce violence in Afghanistan, even if it is temporary. Successful reduction in violence will be followed by intra-Afghan dialogue and phased withdrawal of US troops.

Recalling that millions of Afghans were given refuge for four decades without much international support, praise was rightly showered on Islamabad. The conference reminded that during the peak of the conflict, Afghan refugees in Pakistan numbered nearly 4.5 million. Although many have returned home, over 2.5 million still remain in Pakistan.

Peace in Afghanistan will not be restored by a seven-point action plan nor will it result in repatriation of Afghan refugees

Prime Minister Imran Khan used the occasion to reiterate that Pakistan was keen on peace in Afghanistan at least for the sake of trade and connectivity and that talk of Pakistan of providing safe heavens to militants was rubbish. “Violence in Afghanistan was not in Pakistan’s interest,” he declared, repeating a narrative that has long been used to arouse conviction with the world. By declaring “there is a consensus within Pakistan for peace in Afghanistan,” the prime minister also unwittingly referred to divergent perceptions within state institutions on how to bring about peace in Afghanistan.

The foreign minister spoke about a seven-point action plan for activating the recently established ‘Afghan Refugees Support Platform’ that calls for, among other things, supporting the Afghan peace process, resettlement opportunities for refugees in third countries and creating an international fund for their return home.

But most of what was said in the conference was self-congratulatory. The conference, marking 40 years of Pakistan hosting the world’s largest refugee population, was an occasion for breaking fresh ground on refugee as well as peace in Afghanistan. Unfortunately that was not to be.

Neither the prime minister nor anyone else spoke about the most important initiative about refugees announced by him over a year ago: giving citizenship to Afghan children born in Pakistan. No mention was made of the UN Conventions on Refugees or Convention on Statelessness which Pakistan has steadfastly refused to sign.

There also was no word on need for national legislation on refugees and internally displaced people (IDPs) as a result of military operations in erstwhile tribal districts. There is no data available on children in refugee camps facing statelessness or of other vital areas of concern about refugees and IDPs. The conference ignored these trivialities. When the fact finding missions of bodies like the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan are not allowed to visit camps for internally displaced people, what is the value of data collection?

However, much was made of the newly drawn up seven-point action plan to address refugees’ issues. It drew applause also. But the far-reaching refugee management policy approved in February 2017 was ignored because that could have drawn applause for political adversaries. That policy called for adopting national legislation on refugees and declaring proof of residence (PoR) card for Afghan refugees valid till domestic legislation on refugees was enacted - issues about which the seven-point action plan is silent. The IDPs have been renamed as temporarily displaced persons (TDPs) to avoid making national legislation, so strong is our aversion to domestic legislation.

But peace in Afghanistan will not be restored by the seven-point action plan nor will it result in the repatriation of Afghan refugees. It will be restored only by revisiting the Afghan policy. The unwritten state policy to have a fragmented Afghanistan with a weak Pakistan-installed government that is not too friendly towards India lies at the root of the problem. Our current Afghan policy is based on a zero-sum game with India. The exaggerated Indian threat is designed to create justification for Taliban. Unless this policy changes, words alone that “peace in Afghanistan is peace in Pakistan” will not be sufficient.

It was the result of this policy that explains the prime minister’s remarks early last year that the current Afghan government was a hurdle to peace in Afghanistan. This policy is not new but age old. Remember in the 1980s Pakistan insisted that the Peoples’ Democratic Party (PDPA) government in Afghanistan be replaced with a neutral government.

Remember also that at the time we refused to talk directly with the Kabul government and UN special envoy Diego Cardovez shuttled between Kabul and Islamabad carrying messages to and fro. When finally talks did take place in Geneva, they were called “proximity talks” where Cardovez ridiculously shuttled from room-to-room because we did not want direct talks with a government in Kabul that we did not like. These proximity talks led to Soviet withdrawal but also resulted in civil war and endless bloodshed. PM Imran Khan may have gloated at the conference that Pakistan has delivered Taliban to negotiating table, but negotiations a la ‘proximity’ talks without all Afghan factions, including the current Kabul government, is fraught with the danger of ending in chaos.

The writer is a former senator