Shahbandar in district Sujawal was once a prominent port and a trade hub of Sindh during the Soomra and Kalhora dynasties. But since it was destroyed in 1819 owing to an earthquake, it could never get the same prominence. It simply faded away. At present it’s just a small village of hapless fisherfolk deprived of most basic human needs.

Even as the regular occurrence of cyclones, floods, water scarcity and sea intrusion has affected the lands of this area, the lifestyle of locals has been degraded to an even greater extent.

A number of communities of this area are still dependent on fishing in the sea – this being the main source of livelihood left in the area.

It is a risky occupation, given their meagre resources, but the other option is starvation.

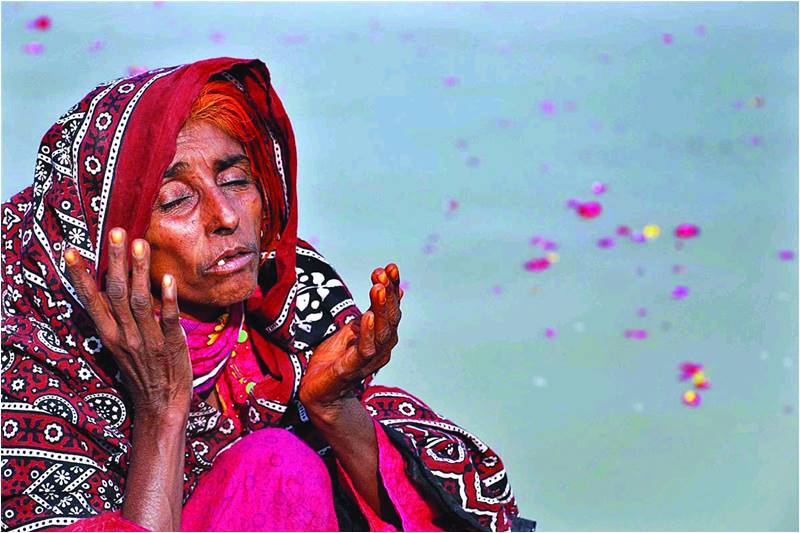

The coastal belt of district Sujawal stretches over tehsils Shahbandar, Kharo Chan and Jati. The people here hold many stories in their hearts which have yet to be put to paper. Here live so many wedded women whose husbands are languishing in Indian jails for years. The women shed tears every night. Sleep became a dream long ago. Their young sons once went out to sea in an effort to catch fish and make a living, but never returned home. The most information that mothers can have in such cases is that their sons were captured by Indian patrols at sea and are now imprisoned in Indian jails.

According to figures from the Pakistan Fisher folk Forum (PFF), a local organization working for the rights of fishing communities of Sindh, “At present 64 fishermen belonging to different fishing communities of Sindh are locked up in different jails of India.”

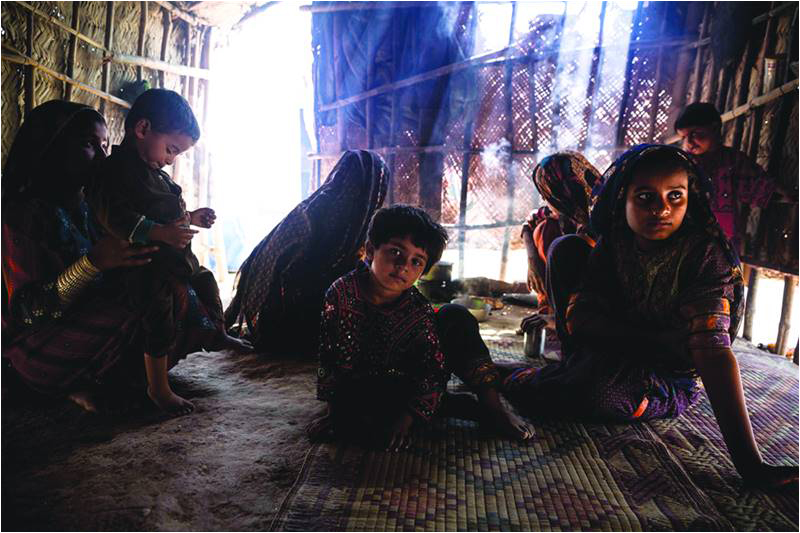

Every other day, the children of these prisoners ask their mothers as to when Baba will come home. They wipe their tears with the border of their Raee (dupatta/long scarf) and fight tears until the child gives up and leaves.

This coastline is witness to a number of love stories that remain painfully incomplete. Many a young woman got promises of companionship for life, but when her lover went out to sea to fish, they simply did not come back. They are missing for years – presumably in jail-cells on the other side of the border.

The stories of pain from these coastal fishing communities are no less than the lament-filled verses of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai’s Sur Kedaro (the poetry that Shah Sain sung about the Karbala Tragedy).

Entire families here live with their eyes transfixed, staring out to sea. They wait in vain for loved ones who are unlikely to sail back home any time soon.

Authorities remain unable to ease their plight.

The writer is a freelance contributor and he can be reached at abbaskhaskheli110@gmail.com

Even as the regular occurrence of cyclones, floods, water scarcity and sea intrusion has affected the lands of this area, the lifestyle of locals has been degraded to an even greater extent.

A number of communities of this area are still dependent on fishing in the sea – this being the main source of livelihood left in the area.

It is a risky occupation, given their meagre resources, but the other option is starvation.

The coastal belt of district Sujawal stretches over tehsils Shahbandar, Kharo Chan and Jati. The people here hold many stories in their hearts which have yet to be put to paper. Here live so many wedded women whose husbands are languishing in Indian jails for years. The women shed tears every night. Sleep became a dream long ago. Their young sons once went out to sea in an effort to catch fish and make a living, but never returned home. The most information that mothers can have in such cases is that their sons were captured by Indian patrols at sea and are now imprisoned in Indian jails.

A number of communities of this area are still dependent on fishing in the sea – this being the main source of livelihood left in the area. It is a risky occupation, given their meagre resources, but the other option is starvation

According to figures from the Pakistan Fisher folk Forum (PFF), a local organization working for the rights of fishing communities of Sindh, “At present 64 fishermen belonging to different fishing communities of Sindh are locked up in different jails of India.”

Every other day, the children of these prisoners ask their mothers as to when Baba will come home. They wipe their tears with the border of their Raee (dupatta/long scarf) and fight tears until the child gives up and leaves.

This coastline is witness to a number of love stories that remain painfully incomplete. Many a young woman got promises of companionship for life, but when her lover went out to sea to fish, they simply did not come back. They are missing for years – presumably in jail-cells on the other side of the border.

The stories of pain from these coastal fishing communities are no less than the lament-filled verses of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai’s Sur Kedaro (the poetry that Shah Sain sung about the Karbala Tragedy).

Entire families here live with their eyes transfixed, staring out to sea. They wait in vain for loved ones who are unlikely to sail back home any time soon.

Authorities remain unable to ease their plight.

The writer is a freelance contributor and he can be reached at abbaskhaskheli110@gmail.com