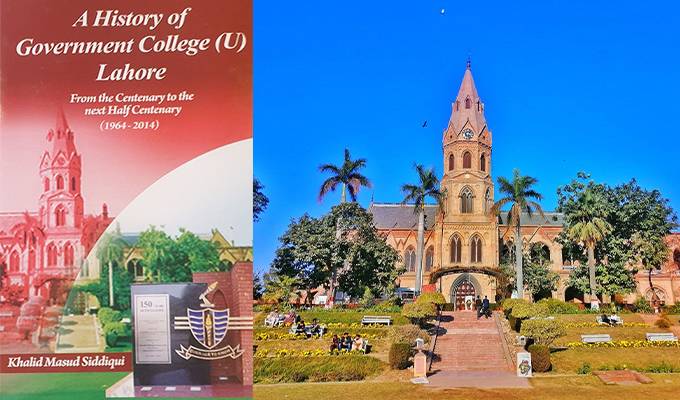

The past can so easily be recorded in cold blood and under the guise of objectivity and impartiality. In Khalid Masud Siddiqui’s historical narrative spanning the years 1964 to 2014, the blood is warm, the gaze insightful and the appraisal involved. This is explained in part by his own close association with Government College (University) from the time he joined it as a young man, much enamoured of its reputation and the imposing building itself, to his tenure as a teacher, head of the English Department and Superintendent of the Quadrangle Hostel (Iqbal Hostel).

The introductory chapter, tracing the origin and growth of the institution through the contribution of various individuals who moulded and nurtured its character makes for enjoyably informed reading. However, Professor Siddiqui’s account is not confined to personalities alone; although many of them were significant, it deals with the college community as a whole and influenced as it was by its ethos.

During the Raj years the academicians at the helm played their part in shaping it as an elite institution, a nativised version of the British Public School crossed with Oxbridge. The College, in miniature, represented an aspect of British national and imperial destiny with a reach and impact well beyond the borders of Britain. It was also to reflect a commitment to notions of liberal enlightenment (endorsed in the College motto itself) which in turn were expected to influence the mindset and “tongue” of the Indians fortunate enough to enter its portals.

The actual physical grounds of the College provided a fertile, undeveloped space upon which the aspirations of individuals within the larger colonial context could be palpably expressed. The attentive landscaping of this space was a significant feature of its personality and the vision behind it, a vision that the present was to carry well into the future in concrete landmarks. Principals would come and go but the College would go on beyond the lives and enterprises of specific administrators and academicians.

Notable in the accounts of the colonial period is the emphasis on character building, and sports and extra-curricular activities as among the important means to achieve that end. While we learn that Dr. Leitner (1864-86), the founder, made an “exceptional contribution to the educational life of the Punjab”, Professor W. Bell (1891-1898) improved the facilities for various sports and “acquired the Presbyterian Church and converted it into a Gymnasium equipped with the latest appliances”. Ironically today, such a decision has been reversed with calls for donations for extending the already ample space of worship.

Professor S. Robson (1898-1912) laid out the Oval and gated and enclosed the premises with a wall, changing forever the bucolic informality of the ground where stray cattle from the city were wont to take their ease. This is difficult to picture in our own times with the gates suggesting Fort Knox and the walls growing taller. The Oval drew the attention of G.D. Sondhi (1939-45) who became the first Indian to assume charge of Principal after H.B. Dunnicliff. Another fervent believer in the sports ethic, Sondhi had the cricket pavilion built and designed the terraced slopes of the ground. Flowering shrubs were planted on each tier and benches installed for students to watch sporting activities. His other great passion: dramatics, found expression in developing the Dramatic Club and personally supervising the building of the open air theatre, the first of its kind in the region.

A distinctive quality of this history is the fairness of its approach. There is no nostalgic harkening back to the good old days of the British, nor is there any abrasive decrying of the former colonials. The Raj era administrators and teachers are lauded when they deserve to be. There is a wealth of information, for example, about their contribution to the sciences and their keen encouragement of a plethora of societies for classical and vernacular languages and translation work. Also noted is the maintenance of high academic standards which were deemed paramount and which greatly influenced the selection of teaching staff. Discipline was an important concern not simply for its own sake, but as essential in ensuring an environment conducive to learning.

Khalid Masud Siddiqui importantly contextualizes the history of Government College within the wider social and political events of the day. While the Tower serenely presided over the relative oasis like calm of the academic locale, contingencies of the external reality could hardly be entirely blocked out. The book recalls the mood of raw tension which prevailed during A.S. Bokhari’s (1947-50) tenure, partly set as it was against the tumult of Partition. Later came the Ahmadiyya riots of the 1950s when one could breathe and move about freely within the compound while the rest of Lahore was locked in an anxious curfew.

Still later, during the Principalship of Dr. Nazir Ahmad ((1959-65), there was a period marked by anti-Ayub Khan agitation, spearheaded by students and notable student leaders like Tariq Ali. The College now, willy-nilly, needed to negotiate a dual identity: one of dispassionate aloofness, the other of greater involvement in momentous political stirrings. There were, of course, less disturbed and more enjoyable occasions too like when in the teeth of serious political unrest in the country, the administration, staff and students valiantly decided to go ahead with the centenary celebrations. These were conducted with true Ravian panache as visiting old alumni were hosted royally, debates and seminars held and to round off the festivities and as a jewel in the crown, a fine production by the prestigious Government College Dramatic Club.

In condensed, highly readable prose, the book also records the changes in culture and attitudes, and there could be no better reflection of these than in the person of Dr. Nazir Ahmad (1959-65). Coming in the wake of a tradition of more formal headship, his distinctly nonconformist, egalitarian personality introduced a considerable eastern-flavoured informality in the general atmosphere and in relations with the student body. Professor Siddiqui gives a vivid picture of the shalwar-, shorts-clad Principal cycling about with his long mane of hair flying in the wind, or emerging from his office or classroom to play impromptu cricket with whosoever was gamesomely inclined to do so. Some of the later Principals attempted to cultivate a similar populist appeal but this was usually more with an eye on the politics of the image, whereas with Dr. Nazir it was spontaneous and non-political. Unfortunately, one of the downsides of this liberalism was a disturbing dent in the overall discipline of the college with serious incidents of student rowdyism and disorder. This was to seep into the future tenures of various administrative Heads.

Professor Rashid (1965-67) emulating some of the older Principals, took a hard line, becoming known as a stickler for orderly conduct. In keeping with the enlivening vignettes of different academicians who people the history and confirm it as one far from being a dry, insipidly neutral exercise, is the account of the Professor, upright in bearing, fastidious in dress waging war equally against laxness as he did against bureaucratic interference in College affairs. He referred to the latter as “the battle of Government College” and in manners and personality fitted to a tee Khaled Ahmed’s description of him in a poem published in the Ravi, as the “vertical” man in a “horizontal world”.

Within the time span of this history there emerged certain recurring concerns. One of these was the see-saw of the student population which burgeoned, necessitating yet more buildings, or was curtailed in order to achieve some measure of quality control. The other was the struggle to quell outbreaks of student violence, themselves a product of the witting or unwitting introduction of divisive politics and mediocrity into the College. Various methods were employed ranging from the severe to milder forms of chastisement. Dr. Mohammad Ajmal’s (1970-72) approach, in which punishment was tempered with genuine tact and shrewd psychologizing met with considerable success. However, it was not till Dr. Khalid Aftab’s (1993-2003) governance, when serious steps combining a centralizing of authority and judicious weeding were taken that the problem was effectively handled and the prestige and reputation of the institution restored. Although the narrative continues to cover subsequent years, there is a conclusion of a kind here with the well-deserved elevation in status of the College to an award giving University in 2002.

Lest it be misconstrued that a considerable portion of this history was mainly one of disturbance, the author faithfully records the fact that despite changes in headship, vision and policy, the College was able to hold its own in overall academic achievement, impressive research work in its science laboratories and in sports. As far as extra-curricular activities were concerned, these too continued unabated and the book drawing on several sources, provides a copious amount of information about them. While the painstaking work involved merits appreciation, the detailing seems almost too much, given that it might be of greater interest to insiders than to the wider reading public.

What is important though, is that through meticulous scholarly research and compilation all the material is there and can be usefully drawn upon in further historical investigation. It needs also to be said that while the author is never niggardly in acknowledging the positive and praiseworthy, he is consistently and incisively critical where necessary. The overall tenor of the narrative is one of loyal championship and is uncompromising in its discernment and forthrightness.

What falls outside the purview of this book and is by way of an entirely subjective post-script has to do with loss and conjecture. It is about the irrevocable diminishing of the winsome beauty and spaciousness of green places, shaded by mature indigenous trees, of a Prospect Hill that once afforded a prospect and fountains that played. There are haunting echoes of past youth, energy and endeavour as one walks the now over boldly-tiled verandahs or speak from the sepia-tinted photographs in the Old Hall. One wishes that the building was protected from its declension into a mere backdrop, permanently on display like some Hollywood set, that its dignified, solid majesty be restored. Beyond the roll-call of distinctions and medals there are questions too about the depth and substance of what lies behind and within the bricks, stone and wood work of this venerable pile. Perhaps another history, an elegiac one, waits in the wings. For the present there is Khalid Masud Siddiqui’s book whose contribution and value are unquestionable.

Professor Sirajuddin is a former Chair of the Department of English Language and Literature and Dean of Arts and Humanities at Punjab University. She is the granddaughter of Prof. G.D. Sondhi and daughter of Professors Sirajuddin and Urmila Sirajuddin

The introductory chapter, tracing the origin and growth of the institution through the contribution of various individuals who moulded and nurtured its character makes for enjoyably informed reading. However, Professor Siddiqui’s account is not confined to personalities alone; although many of them were significant, it deals with the college community as a whole and influenced as it was by its ethos.

During the Raj years the academicians at the helm played their part in shaping it as an elite institution, a nativised version of the British Public School crossed with Oxbridge. The College, in miniature, represented an aspect of British national and imperial destiny with a reach and impact well beyond the borders of Britain. It was also to reflect a commitment to notions of liberal enlightenment (endorsed in the College motto itself) which in turn were expected to influence the mindset and “tongue” of the Indians fortunate enough to enter its portals.

The actual physical grounds of the College provided a fertile, undeveloped space upon which the aspirations of individuals within the larger colonial context could be palpably expressed. The attentive landscaping of this space was a significant feature of its personality and the vision behind it, a vision that the present was to carry well into the future in concrete landmarks. Principals would come and go but the College would go on beyond the lives and enterprises of specific administrators and academicians.

Notable in the accounts of the colonial period is the emphasis on character building, and sports and extra-curricular activities as among the important means to achieve that end. While we learn that Dr. Leitner (1864-86), the founder, made an “exceptional contribution to the educational life of the Punjab”, Professor W. Bell (1891-1898) improved the facilities for various sports and “acquired the Presbyterian Church and converted it into a Gymnasium equipped with the latest appliances”. Ironically today, such a decision has been reversed with calls for donations for extending the already ample space of worship.

Professor S. Robson (1898-1912) laid out the Oval and gated and enclosed the premises with a wall, changing forever the bucolic informality of the ground where stray cattle from the city were wont to take their ease. This is difficult to picture in our own times with the gates suggesting Fort Knox and the walls growing taller. The Oval drew the attention of G.D. Sondhi (1939-45) who became the first Indian to assume charge of Principal after H.B. Dunnicliff. Another fervent believer in the sports ethic, Sondhi had the cricket pavilion built and designed the terraced slopes of the ground. Flowering shrubs were planted on each tier and benches installed for students to watch sporting activities. His other great passion: dramatics, found expression in developing the Dramatic Club and personally supervising the building of the open air theatre, the first of its kind in the region.

A distinctive quality of this history is the fairness of its approach. There is no nostalgic harkening back to the good old days of the British, nor is there any abrasive decrying of the former colonials. The Raj era administrators and teachers are lauded when they deserve to be. There is a wealth of information, for example, about their contribution to the sciences and their keen encouragement of a plethora of societies for classical and vernacular languages and translation work. Also noted is the maintenance of high academic standards which were deemed paramount and which greatly influenced the selection of teaching staff. Discipline was an important concern not simply for its own sake, but as essential in ensuring an environment conducive to learning.

Khalid Masud Siddiqui importantly contextualizes the history of Government College within the wider social and political events of the day. While the Tower serenely presided over the relative oasis like calm of the academic locale, contingencies of the external reality could hardly be entirely blocked out. The book recalls the mood of raw tension which prevailed during A.S. Bokhari’s (1947-50) tenure, partly set as it was against the tumult of Partition. Later came the Ahmadiyya riots of the 1950s when one could breathe and move about freely within the compound while the rest of Lahore was locked in an anxious curfew.

Still later, during the Principalship of Dr. Nazir Ahmad ((1959-65), there was a period marked by anti-Ayub Khan agitation, spearheaded by students and notable student leaders like Tariq Ali. The College now, willy-nilly, needed to negotiate a dual identity: one of dispassionate aloofness, the other of greater involvement in momentous political stirrings. There were, of course, less disturbed and more enjoyable occasions too like when in the teeth of serious political unrest in the country, the administration, staff and students valiantly decided to go ahead with the centenary celebrations. These were conducted with true Ravian panache as visiting old alumni were hosted royally, debates and seminars held and to round off the festivities and as a jewel in the crown, a fine production by the prestigious Government College Dramatic Club.

In condensed, highly readable prose, the book also records the changes in culture and attitudes, and there could be no better reflection of these than in the person of Dr. Nazir Ahmad (1959-65). Coming in the wake of a tradition of more formal headship, his distinctly nonconformist, egalitarian personality introduced a considerable eastern-flavoured informality in the general atmosphere and in relations with the student body. Professor Siddiqui gives a vivid picture of the shalwar-, shorts-clad Principal cycling about with his long mane of hair flying in the wind, or emerging from his office or classroom to play impromptu cricket with whosoever was gamesomely inclined to do so. Some of the later Principals attempted to cultivate a similar populist appeal but this was usually more with an eye on the politics of the image, whereas with Dr. Nazir it was spontaneous and non-political. Unfortunately, one of the downsides of this liberalism was a disturbing dent in the overall discipline of the college with serious incidents of student rowdyism and disorder. This was to seep into the future tenures of various administrative Heads.

Professor Rashid (1965-67) emulating some of the older Principals, took a hard line, becoming known as a stickler for orderly conduct. In keeping with the enlivening vignettes of different academicians who people the history and confirm it as one far from being a dry, insipidly neutral exercise, is the account of the Professor, upright in bearing, fastidious in dress waging war equally against laxness as he did against bureaucratic interference in College affairs. He referred to the latter as “the battle of Government College” and in manners and personality fitted to a tee Khaled Ahmed’s description of him in a poem published in the Ravi, as the “vertical” man in a “horizontal world”.

Within the time span of this history there emerged certain recurring concerns. One of these was the see-saw of the student population which burgeoned, necessitating yet more buildings, or was curtailed in order to achieve some measure of quality control. The other was the struggle to quell outbreaks of student violence, themselves a product of the witting or unwitting introduction of divisive politics and mediocrity into the College. Various methods were employed ranging from the severe to milder forms of chastisement. Dr. Mohammad Ajmal’s (1970-72) approach, in which punishment was tempered with genuine tact and shrewd psychologizing met with considerable success. However, it was not till Dr. Khalid Aftab’s (1993-2003) governance, when serious steps combining a centralizing of authority and judicious weeding were taken that the problem was effectively handled and the prestige and reputation of the institution restored. Although the narrative continues to cover subsequent years, there is a conclusion of a kind here with the well-deserved elevation in status of the College to an award giving University in 2002.

Lest it be misconstrued that a considerable portion of this history was mainly one of disturbance, the author faithfully records the fact that despite changes in headship, vision and policy, the College was able to hold its own in overall academic achievement, impressive research work in its science laboratories and in sports. As far as extra-curricular activities were concerned, these too continued unabated and the book drawing on several sources, provides a copious amount of information about them. While the painstaking work involved merits appreciation, the detailing seems almost too much, given that it might be of greater interest to insiders than to the wider reading public.

What is important though, is that through meticulous scholarly research and compilation all the material is there and can be usefully drawn upon in further historical investigation. It needs also to be said that while the author is never niggardly in acknowledging the positive and praiseworthy, he is consistently and incisively critical where necessary. The overall tenor of the narrative is one of loyal championship and is uncompromising in its discernment and forthrightness.

What falls outside the purview of this book and is by way of an entirely subjective post-script has to do with loss and conjecture. It is about the irrevocable diminishing of the winsome beauty and spaciousness of green places, shaded by mature indigenous trees, of a Prospect Hill that once afforded a prospect and fountains that played. There are haunting echoes of past youth, energy and endeavour as one walks the now over boldly-tiled verandahs or speak from the sepia-tinted photographs in the Old Hall. One wishes that the building was protected from its declension into a mere backdrop, permanently on display like some Hollywood set, that its dignified, solid majesty be restored. Beyond the roll-call of distinctions and medals there are questions too about the depth and substance of what lies behind and within the bricks, stone and wood work of this venerable pile. Perhaps another history, an elegiac one, waits in the wings. For the present there is Khalid Masud Siddiqui’s book whose contribution and value are unquestionable.

Professor Sirajuddin is a former Chair of the Department of English Language and Literature and Dean of Arts and Humanities at Punjab University. She is the granddaughter of Prof. G.D. Sondhi and daughter of Professors Sirajuddin and Urmila Sirajuddin