In one of his recent press conference, Prime Minister Imran Khan criticised the 18th Constitutional Amendment and added that Pakistan does not have the capacity to collect taxes. He said that the provinces had failed to collect taxes and the centre has gone bankrupt.

While blaming the 18th amendment for this crisis, PM Khan very conveniently overlooked the rise of the informal economy in Pakistan over the last three decades. According to recent research, about 71 per cent of informality was found in Pakistan’s economy. Both economic and political factors are responsible for this increase. Economic factors include rising unemployment and changing tax rates. At the same time, political instability, the overall legislative system, corruption and government regulations are the political factors that led to the rise of the informal economy in Pakistan. If this informality of economic activity is controlled well by the government, it can stimulate economic growth in the country.

When it comes to Balochistan, this informality in the economy is compounded by trafficking of drugs, humans and vehicles. This is a great concern for Balochistan because high informality means greater tax evasion and more fiscal loss for the government.

Balochistan is part of the transitional trade route as it shares long borders with Iran and Afghanistan and has a vast coastline which is exposed to international traffickers. The province offers perfect routes for these peddlers to access international markets. These illegal dealings are causing serious social problems for the people of Balochistan.

According to a United Nations report, Balochistan, despite a low population, represents 70 per cent of the national use of methamphetamines and the prevalence of opiate users was 1.6 per cent of the population. The report furthers states that Gwadar, already being utilised for illegal immigration, is becoming a major transit point for drugs. It claimed the rapid rise in trade volume in the region was likely to overwhelm customs and law enforcement agencies and the port’s vicinity to regional trade centres would be most likely see Gwadar being targeted by more traffickers.

In recent years, the Makran coast has also become popular for this purpose. In fact, the long and virtually unguarded coastline is seen as the securest route to be adopted by the traffickers.

Apart from economic costs, the impact of drug use on public life is profound. The people of Balochistan are facing problems such as family and marital disputes, high rates of unemployment, elevated risks of transmitting HIV and other communicable diseases. Apart from this, police demand bribes from drug users so the user can avoid arrest or be released from police custody without charge.

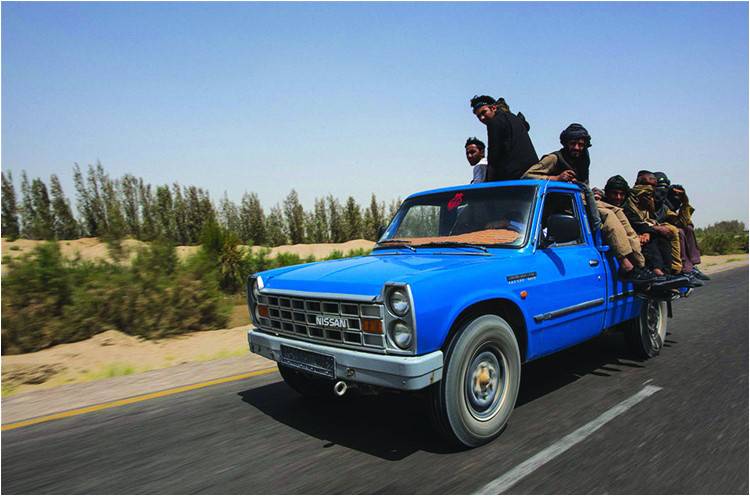

Second, on the list is human trafficking and it is at its peak in Balochistan’s border areas. Smugglers have been using land routes of Mand and Taftan, without being challenged by the authorities concerned. According to a report, nearly 10,000 people try to cross the border illegally every month in the hope of a new future; and many die in the process. The journey is a test of their nerve: sometimes they have to sit in containers, and sometimes they have to face the onslaught of Iranian forces. Regional representatives of these areas should make the people aware of the negative effects of this unlawful act, which is ruining the reputation of their families as well as of the whole nation. The government should strive to create more job opportunities to make people turn away from illicit activities.

The youth in Balochistan would prefer to smuggle than being unemployed. The prospects of education are so bleak in the region that high school students abandon education to pursue a career in smuggling of fuel or vehicles. Districts of Panjgur and Noshki are worst hit by smuggling. Previously, these two districts were among the top producers of doctors, engineers and civil servants. Now, participation in these sectors has dropped greatly.

Nearly nine routes are used for fuel smuggling including including Qamar-Din-Karez, Badini, Afghanistan-Toba Achakzai and Barabcha (Dalbandin) while from Iran the principal routes for the purpose of smuggling include Taftan, Mashkhai, Panjgur, Noshki, Mastung, Quetta, Surab, Khuzdar, Karkh and Shahdad Kot.

Balochistan shares approximately 1,615 kilometers of a border with Iran and Afghanistan. On this extensive terrain, it is a great to check smuggling in an efficient manner. There are serious challenges for tax authorities to combat smugglers in the wake of the erratic security situation, absence of human resources and materials. Due to lack of resources, the presence of customs is mostly on the two border crossing points of Taftan and Chaman. Leaving the rest of the province unattended gives a great advantage to the smugglers. Smuggling of petroleum products causes an estimated loss of more than Rs30 billion every year. Smuggling of vehicles adds further to the losses of Balochistan.

By the orders of the government in mid-February, the Pakistan-Afghanistan border crossing was sealed. But the closure had little or no impact on smuggled vehicles that continue to roam the valleys of Balochistan. There are scores of showrooms of Kabuli vehicles in the heart of Quetta. On the bridge from Sariab Road to Double Road, hundreds of Kabuli vehicles of various models can be seen parked in these showrooms. This illegal industry has effectively flooded the Internet too. There are dozens of pages on Facebook that share pictures of different models of such vehicles. Though most Kabuli vehicles enter via the Chaman border, Chaghai and Nushki districts also share a porous border with Afghanistan, which forms another route. According to an unofficial estimate, it is believed that there are nearly 60,000 Kabuli vehicles in Quetta and thousands more in other districts. These vehicles cost the economy a great deal each year when no tax revenue is collected for these cars.

To curb this menace of trafficking, we must design a consolidated and coordinated approach with the collective assistance of the government, civil society and the private sector. Successful implementation of any plan would also require a sustained commitment from all stakeholders. Some of the recommendations to be implemented by competent provincial authorities and other stakeholders can be: establishing a management system that ensures monitoring for and preventing possible deviation, raising awareness among policymakers and clinicians, parents, young people, and teachers on the consequences of trafficking.

Finally, the Education Ministry at provincial and district levels, along with civil society organisations and the general public, needs to increase support for design and implementation of programs that are evidence-based and consistent with international best practices. One such best practice can be the use of social marketing framework for design and implementation of interventions that focus on upstream policymaking and awareness.

While blaming the 18th amendment for this crisis, PM Khan very conveniently overlooked the rise of the informal economy in Pakistan over the last three decades. According to recent research, about 71 per cent of informality was found in Pakistan’s economy. Both economic and political factors are responsible for this increase. Economic factors include rising unemployment and changing tax rates. At the same time, political instability, the overall legislative system, corruption and government regulations are the political factors that led to the rise of the informal economy in Pakistan. If this informality of economic activity is controlled well by the government, it can stimulate economic growth in the country.

When it comes to Balochistan, this informality in the economy is compounded by trafficking of drugs, humans and vehicles. This is a great concern for Balochistan because high informality means greater tax evasion and more fiscal loss for the government.

Balochistan is part of the transitional trade route as it shares long borders with Iran and Afghanistan and has a vast coastline which is exposed to international traffickers. The province offers perfect routes for these peddlers to access international markets. These illegal dealings are causing serious social problems for the people of Balochistan.

The youth in Balochistan would prefer to smuggle than being unemployed. The prospects of education are so bleak in the region that high school students abandon education to pursue a career in smuggling of fuel or vehicles

According to a United Nations report, Balochistan, despite a low population, represents 70 per cent of the national use of methamphetamines and the prevalence of opiate users was 1.6 per cent of the population. The report furthers states that Gwadar, already being utilised for illegal immigration, is becoming a major transit point for drugs. It claimed the rapid rise in trade volume in the region was likely to overwhelm customs and law enforcement agencies and the port’s vicinity to regional trade centres would be most likely see Gwadar being targeted by more traffickers.

In recent years, the Makran coast has also become popular for this purpose. In fact, the long and virtually unguarded coastline is seen as the securest route to be adopted by the traffickers.

Apart from economic costs, the impact of drug use on public life is profound. The people of Balochistan are facing problems such as family and marital disputes, high rates of unemployment, elevated risks of transmitting HIV and other communicable diseases. Apart from this, police demand bribes from drug users so the user can avoid arrest or be released from police custody without charge.

Second, on the list is human trafficking and it is at its peak in Balochistan’s border areas. Smugglers have been using land routes of Mand and Taftan, without being challenged by the authorities concerned. According to a report, nearly 10,000 people try to cross the border illegally every month in the hope of a new future; and many die in the process. The journey is a test of their nerve: sometimes they have to sit in containers, and sometimes they have to face the onslaught of Iranian forces. Regional representatives of these areas should make the people aware of the negative effects of this unlawful act, which is ruining the reputation of their families as well as of the whole nation. The government should strive to create more job opportunities to make people turn away from illicit activities.

The youth in Balochistan would prefer to smuggle than being unemployed. The prospects of education are so bleak in the region that high school students abandon education to pursue a career in smuggling of fuel or vehicles. Districts of Panjgur and Noshki are worst hit by smuggling. Previously, these two districts were among the top producers of doctors, engineers and civil servants. Now, participation in these sectors has dropped greatly.

Nearly nine routes are used for fuel smuggling including including Qamar-Din-Karez, Badini, Afghanistan-Toba Achakzai and Barabcha (Dalbandin) while from Iran the principal routes for the purpose of smuggling include Taftan, Mashkhai, Panjgur, Noshki, Mastung, Quetta, Surab, Khuzdar, Karkh and Shahdad Kot.

Balochistan shares approximately 1,615 kilometers of a border with Iran and Afghanistan. On this extensive terrain, it is a great to check smuggling in an efficient manner. There are serious challenges for tax authorities to combat smugglers in the wake of the erratic security situation, absence of human resources and materials. Due to lack of resources, the presence of customs is mostly on the two border crossing points of Taftan and Chaman. Leaving the rest of the province unattended gives a great advantage to the smugglers. Smuggling of petroleum products causes an estimated loss of more than Rs30 billion every year. Smuggling of vehicles adds further to the losses of Balochistan.

By the orders of the government in mid-February, the Pakistan-Afghanistan border crossing was sealed. But the closure had little or no impact on smuggled vehicles that continue to roam the valleys of Balochistan. There are scores of showrooms of Kabuli vehicles in the heart of Quetta. On the bridge from Sariab Road to Double Road, hundreds of Kabuli vehicles of various models can be seen parked in these showrooms. This illegal industry has effectively flooded the Internet too. There are dozens of pages on Facebook that share pictures of different models of such vehicles. Though most Kabuli vehicles enter via the Chaman border, Chaghai and Nushki districts also share a porous border with Afghanistan, which forms another route. According to an unofficial estimate, it is believed that there are nearly 60,000 Kabuli vehicles in Quetta and thousands more in other districts. These vehicles cost the economy a great deal each year when no tax revenue is collected for these cars.

To curb this menace of trafficking, we must design a consolidated and coordinated approach with the collective assistance of the government, civil society and the private sector. Successful implementation of any plan would also require a sustained commitment from all stakeholders. Some of the recommendations to be implemented by competent provincial authorities and other stakeholders can be: establishing a management system that ensures monitoring for and preventing possible deviation, raising awareness among policymakers and clinicians, parents, young people, and teachers on the consequences of trafficking.

Finally, the Education Ministry at provincial and district levels, along with civil society organisations and the general public, needs to increase support for design and implementation of programs that are evidence-based and consistent with international best practices. One such best practice can be the use of social marketing framework for design and implementation of interventions that focus on upstream policymaking and awareness.