The 1980s is the decade when Pakistan’s social fabric was completely torn apart by the self-declared reformer, General Zia-ul Haq—a dictator — who ruled for 11 years until he perished in a mysterious plane crash. After his death, the initial attitude of the military gave the impression masses that Pakistan would become a “normal” country from then on, where the democracy would flourish and everyone would have a freedom dividend. Although the way power transfer was manipulated by the new president and the military, which was questioned by the democratic-minded experts, everyone was hopeful for the better days. Days after the oath-taking ceremony of Ms. Benazir Bhutto, I was going to the US for higher education. I remember that I went to see one of my uncles. He asked as to why I was going to the US, when things were getting better. However, over the years, everyone realised that Zia’s 11 dark years left a permanent scar on the people’s psyche, which entirely confused people, and instead of becoming a nation, we became a rudder-less mob.

In 2014, the military once again began a new adventure — the “Imran Project.” This time they did not bring themselves to direct rule, but they created a stooge, boosted his popularity by pressuring the media and political figures, revamped his political party, and pushed the so-called “electables” from other parties. With flamboyant election day rigging, they brought their stooge to power so that they could wipe off all those popular leaders who could question their intervention in politics, question their business interests and question their pensions for retired servicemen which they draw from the civilian budget.

Unfortunately, their linear thought process made them bet their money on the handicapped horse.

The “Imran Project” failed from the very first day, and by the end of the third year, the country’s economy went into the doldrums, with a failed foreign policy in which most of the countries reevaluated their relations with Pakistan, and even with the conspicuous pressure on the media by the government, intelligence agencies and the military–which brought him in power after the heavily rigged elections — could not tame some top-of-the-line journalists because they made their voices heard through the noisy social media.

Pakistan’s establishment has a long-term fascination with the presidential system, where the concept of the unity of command applies and the military can control every decision, which, in the current system, is getting almost impossible, especially after the approval of the 18th constitutional amendment. Whenever the military came to power by coup d’état, they imposed a presidential system. When the Pakistan Peoples Party won the elections in 2008, it was a presidential type of government, in which the President had the power to dissolve the National Assembly and call for the new elections. The PPP could continue, and their President Asif Zardari could be the most powerful civilian President, at least for the next 5 years. However, he relinquished his enormous powers through the 18th constitutional amendment and handed them over to the parliament – which is the real owner of such powers, according to the constitution of Pakistan.

The debate on the mass media of Pakistan about bringing in a presidential system and abolishing the parliamentary form of government is going on for some years. Bringing Khan in power is also seen as a part of the same plan, orchestrated by the establishment. The supporters show the GDP growth, economic data, and other reports to argue that during the presidential systems, under the military dictatorships, the country did better economically than it did when the democratic governments were in office. Although just the snapshots of economic growth numbers cannot be the sign of perpetual prosperity even if it were, there are more serious factors that make the Presidential system — no matter the President is brought by votes — unworkable in Pakistan. The advocates conveniently ignore those ground realities just to mislead the masses.

Pakistan is a multi-cultural and multi-ethnic society. Every section has a significant presence in the country, and they demand a power share. Ayub Khan’s dictatorship created discomfort among the Bengali population and they started demanding secession from Pakistan. India, with its security paranoia, exploited the situation and Pakistan broke into two. The presidential system would let no one else other than a candidate from one province come into power, which would demoralise the other provinces in the country. That could culminate in a situation where other provinces would demand to secede from Pakistan – as East Pakistan did.

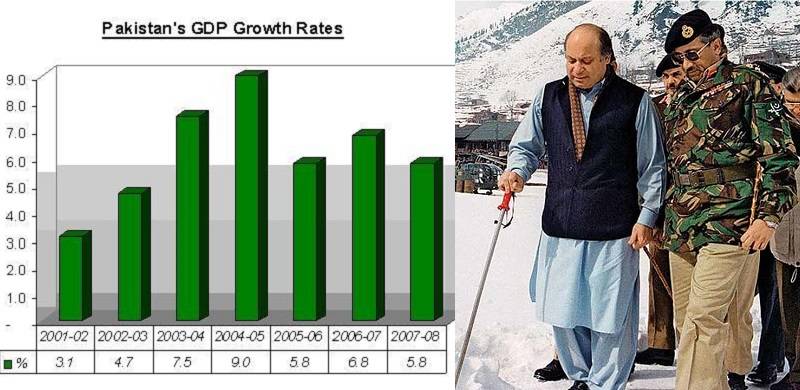

Throughout 75 years of Pakistan’s history, Pakistan was under direct military rule for 32 years, and the remaining time it was governed by fragile military-controlled democracies and a nexus of the military and the bureaucracy. In the course of Imran Khan’s 45 months of government, the country was largely run by the military and Khan was only struggling to wipe out all his opposition. The military took the position of ruler and kingmaker during intermittent periods of democracy. Although the GDP annual growth rate is not the only indicator of a good or bad economy, for the sake of discussion, let’s look at this factor.

During the 32 years of direct military rule, the economy grew at an average rate of 6.3% per year. However, for the remaining years, the GDP growth was less impressive, when it increased by less than 5% annually.

The question arises: does this mean that presidents under the presidential military-ruled form are the better managers of the economy?

This is a myth that is widely projected by the apologists of military rules and dictatorship. However, this troublesome question can be addressed to some extent by closely looking at the performance of the economy under four Generals, who ruled directly for 32 years of Pakistan’s history as Presidents of Pakistan.

A comparison of the GDP growth data reveals that the GDP growth was uniformly increased during PML-N’s second government (1997-1999) and third government (2013-2018) and PPP’s third government (2008-2013). Looking at the PPP’s third government (2008-2013) and the PML-N’s third government, one may observe that in the two democratic governments, the GDP growth rate increased almost uniformly from 2010 until 2018, but it dropped suddenly when the military-backed government of PTI was brought into power and the decision making was largely moved to the establishment’s favorites inside and outside the new government. The 4.26% growth in 2000 was the continuation of the PML-N government but just in one year after General Musharraf seized power, the country observed an almost 53% decline in the growth rate (4.26% to 1.98%). After 9/11, when Pakistan became a front-line state for the US to launch military operations in Afghanistan, money started pumping into its economy and the loans were rescheduled, which brought economic stability. A very similar trend can be observed during Zia’s martial law. The growth in 1978 was the projection from 1977 but a 53% (from 8.0% to 3.75%) decline in the growth rate was observed in 1979, just before foreign help came after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. So, the myth that foreign help has nothing to do with the economic gains during the Generals’ rule is rejected by the real-world data.

By looking at data, one may conclude that the economy performed well under dictators for some time, but it was not because of great economic management and any deep structural changes which were brought about by the regimes.

Let’s analyse General Musharraf’s 9-year dictatorship as a test case, and observe how much truth there is in the myths about the booming economy during his self-appointed presidency.

Expanding the GDP growth trend during the second PML-N tenure and Musharraf’s governments, one can observe that the GDP growth rate was the highest — close to 8% — during the fiscal year 2004/05. By definition, the GDP growth rate is defined as the average growth in its components. The outstanding feature of 2005 was where Pakistan graduated from the IMF’s Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF) program in December 2004. The agricultural sector broke out of its four-year slump to record growth that exceeded the target goal, contributing to the high growth rate during the fiscal year 2004/05 compared to 2003/04. This increase was primarily because of favourable weather. Another factor in the sudden growth was the growth in the banking and automobile industries. During the fiscal year 2004/05, when GDP growth was around 8%, the banking sector — one component — growth rate was 29% and the automobile sector, another component — was close to 45%. In 2002, the State Bank of Pakistan allowed consumer financing, which enabled common people to get loans for houses, cars, household appliances even personal loans for their children’s weddings and extravagant vacations. The banks made enormous profits out of consumers’ credit. Since a large part of the credit goes to buy cars and motorcycles, automobile production went up by 40-45%. According to economists, the economic growth during that time period was a “single-legged” growth and that one leg was consumer financing, and the second leg, industrialisation, was missing from the equation.

The fragilities in the economic model introduced by Musharraf’s economic team caused a sudden decline in the GDP growth in 2006 (from 7.66% to 6.17%), compared to the extraordinary growth of 2005, and the trend continued until 2008 when the growth rate became just 1.7%. The trade deficit in the first half of 2006 was not only significantly exceeded by the one during the same period of the previous fiscal year, but it also outpaced the total trade deficit of the previous fiscal year, because of which an inflationary pressure came to bear on the economy – and the inflation rate rose from the previously less than 2% in 2003/04 to around 12% in 2005/06.

The Zardari government had to inherit around a 12% inflation rate and a high trade deficit. Similarly, Benazir Bhutto’s first government had to deal with the debt burden from Zia’s 11 years. Asif Zardari’s government had to deal with the massive foreign exchange crisis created by Musharraf's regime's nine “glorious” years.

Recently, Dr. Niaz Murtaza, a well-known economist, has created a table showing how the economies behaved during the Musharraf’s military, PPP, PML (N), and the PTI governments. He based his analysis on several economic indicators, like GDP annual growth rate, inflation rate, fiscal deficit, current account deficit, interest rate, etc. He found that Musharraf’s presidential government and PTI’s “hybrid” government did not do as well as the democratically elected PPP and PML (N) governments.

Pakistan’s senior economist at the World Bank and ex-Finance Minister Dr. Shahid Javed Burki explains the myth about the presidential/military rule in his book Changing Perceptions, Altered Reality: Pakistan’s Economy Under Musharraf, 1999-2006. He writes: “During the eleven years of the period of Ayub Khan, the GDP increased at a rate of 6.7% a year. In the Zia-ul-Haq period, which lasted also for eleven years, the GDP grew at 6.4% a year. This should not imply that the Pakistani economy does well when men in uniform are in control. What it does show is that during periods of military rule, Pakistan could draw significant amounts of foreign capital, which augmented its low rate of domestic savings and produced reasonable amounts of investment. But during military rule, the economy also became extremely dependent on external capital flows. This created enormous vulnerability.”

Describing economic growth during the dictatorship of Gen Musharraf, Dr. Burki writes, “According to one point of view in this debate, the brisk performance in 2004-5 was the consequence of the happy confluence of several events. Those who held that view—and I belong to that group—thought there was a low probability of that happening again.”

“Even during the alleged economic growth that took place under Gen Musharraf’s rule, not everyone gained. The poor, in particular, actually suffered more,” writes Dr. Burki.

When countries are used as the laboratory to run experiments by powerful institutions, the masses have to face the consequences. The Pakistani masses are paying the price of establishments’ failed experiments since 1958. Even after the ignominious breakup of Pakistan, the establishment did not stop doing its experiments. The creation of a “real leader” was the most recent experiment which was – as expected -- failed miserably.

During the coming decades, the failed experiment would leave significant scars on the social fabric of the nation, in the same way as the long-lasting blisters were inflicted on the society by Zia’s adventurism, which -- even after 25 years of his death -- are festering.

In 2014, the military once again began a new adventure — the “Imran Project.” This time they did not bring themselves to direct rule, but they created a stooge, boosted his popularity by pressuring the media and political figures, revamped his political party, and pushed the so-called “electables” from other parties. With flamboyant election day rigging, they brought their stooge to power so that they could wipe off all those popular leaders who could question their intervention in politics, question their business interests and question their pensions for retired servicemen which they draw from the civilian budget.

Unfortunately, their linear thought process made them bet their money on the handicapped horse.

The “Imran Project” failed from the very first day, and by the end of the third year, the country’s economy went into the doldrums, with a failed foreign policy in which most of the countries reevaluated their relations with Pakistan, and even with the conspicuous pressure on the media by the government, intelligence agencies and the military–which brought him in power after the heavily rigged elections — could not tame some top-of-the-line journalists because they made their voices heard through the noisy social media.

Pakistan’s establishment has a long-term fascination with the presidential system, where the concept of the unity of command applies and the military can control every decision, which, in the current system, is getting almost impossible, especially after the approval of the 18th constitutional amendment. Whenever the military came to power by coup d’état, they imposed a presidential system. When the Pakistan Peoples Party won the elections in 2008, it was a presidential type of government, in which the President had the power to dissolve the National Assembly and call for the new elections. The PPP could continue, and their President Asif Zardari could be the most powerful civilian President, at least for the next 5 years. However, he relinquished his enormous powers through the 18th constitutional amendment and handed them over to the parliament – which is the real owner of such powers, according to the constitution of Pakistan.

The debate on the mass media of Pakistan about bringing in a presidential system and abolishing the parliamentary form of government is going on for some years. Bringing Khan in power is also seen as a part of the same plan, orchestrated by the establishment. The supporters show the GDP growth, economic data, and other reports to argue that during the presidential systems, under the military dictatorships, the country did better economically than it did when the democratic governments were in office. Although just the snapshots of economic growth numbers cannot be the sign of perpetual prosperity even if it were, there are more serious factors that make the Presidential system — no matter the President is brought by votes — unworkable in Pakistan. The advocates conveniently ignore those ground realities just to mislead the masses.

Pakistan is a multi-cultural and multi-ethnic society. Every section has a significant presence in the country, and they demand a power share. Ayub Khan’s dictatorship created discomfort among the Bengali population and they started demanding secession from Pakistan. India, with its security paranoia, exploited the situation and Pakistan broke into two. The presidential system would let no one else other than a candidate from one province come into power, which would demoralise the other provinces in the country. That could culminate in a situation where other provinces would demand to secede from Pakistan – as East Pakistan did.

Throughout 75 years of Pakistan’s history, Pakistan was under direct military rule for 32 years, and the remaining time it was governed by fragile military-controlled democracies and a nexus of the military and the bureaucracy. In the course of Imran Khan’s 45 months of government, the country was largely run by the military and Khan was only struggling to wipe out all his opposition. The military took the position of ruler and kingmaker during intermittent periods of democracy. Although the GDP annual growth rate is not the only indicator of a good or bad economy, for the sake of discussion, let’s look at this factor.

During the 32 years of direct military rule, the economy grew at an average rate of 6.3% per year. However, for the remaining years, the GDP growth was less impressive, when it increased by less than 5% annually.

The question arises: does this mean that presidents under the presidential military-ruled form are the better managers of the economy?

This is a myth that is widely projected by the apologists of military rules and dictatorship. However, this troublesome question can be addressed to some extent by closely looking at the performance of the economy under four Generals, who ruled directly for 32 years of Pakistan’s history as Presidents of Pakistan.

Describing economic growth during the dictatorship of Gen Musharraf, Dr. Burki writes, “According to one point of view in this debate, the brisk performance in 2004-5 was the consequence of the happy confluence of several events. Those who held that view—and I belong to that group—thought there was a low probability of that happening again”

A comparison of the GDP growth data reveals that the GDP growth was uniformly increased during PML-N’s second government (1997-1999) and third government (2013-2018) and PPP’s third government (2008-2013). Looking at the PPP’s third government (2008-2013) and the PML-N’s third government, one may observe that in the two democratic governments, the GDP growth rate increased almost uniformly from 2010 until 2018, but it dropped suddenly when the military-backed government of PTI was brought into power and the decision making was largely moved to the establishment’s favorites inside and outside the new government. The 4.26% growth in 2000 was the continuation of the PML-N government but just in one year after General Musharraf seized power, the country observed an almost 53% decline in the growth rate (4.26% to 1.98%). After 9/11, when Pakistan became a front-line state for the US to launch military operations in Afghanistan, money started pumping into its economy and the loans were rescheduled, which brought economic stability. A very similar trend can be observed during Zia’s martial law. The growth in 1978 was the projection from 1977 but a 53% (from 8.0% to 3.75%) decline in the growth rate was observed in 1979, just before foreign help came after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. So, the myth that foreign help has nothing to do with the economic gains during the Generals’ rule is rejected by the real-world data.

By looking at data, one may conclude that the economy performed well under dictators for some time, but it was not because of great economic management and any deep structural changes which were brought about by the regimes.

Let’s analyse General Musharraf’s 9-year dictatorship as a test case, and observe how much truth there is in the myths about the booming economy during his self-appointed presidency.

Expanding the GDP growth trend during the second PML-N tenure and Musharraf’s governments, one can observe that the GDP growth rate was the highest — close to 8% — during the fiscal year 2004/05. By definition, the GDP growth rate is defined as the average growth in its components. The outstanding feature of 2005 was where Pakistan graduated from the IMF’s Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF) program in December 2004. The agricultural sector broke out of its four-year slump to record growth that exceeded the target goal, contributing to the high growth rate during the fiscal year 2004/05 compared to 2003/04. This increase was primarily because of favourable weather. Another factor in the sudden growth was the growth in the banking and automobile industries. During the fiscal year 2004/05, when GDP growth was around 8%, the banking sector — one component — growth rate was 29% and the automobile sector, another component — was close to 45%. In 2002, the State Bank of Pakistan allowed consumer financing, which enabled common people to get loans for houses, cars, household appliances even personal loans for their children’s weddings and extravagant vacations. The banks made enormous profits out of consumers’ credit. Since a large part of the credit goes to buy cars and motorcycles, automobile production went up by 40-45%. According to economists, the economic growth during that time period was a “single-legged” growth and that one leg was consumer financing, and the second leg, industrialisation, was missing from the equation.

The fragilities in the economic model introduced by Musharraf’s economic team caused a sudden decline in the GDP growth in 2006 (from 7.66% to 6.17%), compared to the extraordinary growth of 2005, and the trend continued until 2008 when the growth rate became just 1.7%. The trade deficit in the first half of 2006 was not only significantly exceeded by the one during the same period of the previous fiscal year, but it also outpaced the total trade deficit of the previous fiscal year, because of which an inflationary pressure came to bear on the economy – and the inflation rate rose from the previously less than 2% in 2003/04 to around 12% in 2005/06.

The Zardari government had to inherit around a 12% inflation rate and a high trade deficit. Similarly, Benazir Bhutto’s first government had to deal with the debt burden from Zia’s 11 years. Asif Zardari’s government had to deal with the massive foreign exchange crisis created by Musharraf's regime's nine “glorious” years.

Recently, Dr. Niaz Murtaza, a well-known economist, has created a table showing how the economies behaved during the Musharraf’s military, PPP, PML (N), and the PTI governments. He based his analysis on several economic indicators, like GDP annual growth rate, inflation rate, fiscal deficit, current account deficit, interest rate, etc. He found that Musharraf’s presidential government and PTI’s “hybrid” government did not do as well as the democratically elected PPP and PML (N) governments.

Pakistan’s senior economist at the World Bank and ex-Finance Minister Dr. Shahid Javed Burki explains the myth about the presidential/military rule in his book Changing Perceptions, Altered Reality: Pakistan’s Economy Under Musharraf, 1999-2006. He writes: “During the eleven years of the period of Ayub Khan, the GDP increased at a rate of 6.7% a year. In the Zia-ul-Haq period, which lasted also for eleven years, the GDP grew at 6.4% a year. This should not imply that the Pakistani economy does well when men in uniform are in control. What it does show is that during periods of military rule, Pakistan could draw significant amounts of foreign capital, which augmented its low rate of domestic savings and produced reasonable amounts of investment. But during military rule, the economy also became extremely dependent on external capital flows. This created enormous vulnerability.”

Describing economic growth during the dictatorship of Gen Musharraf, Dr. Burki writes, “According to one point of view in this debate, the brisk performance in 2004-5 was the consequence of the happy confluence of several events. Those who held that view—and I belong to that group—thought there was a low probability of that happening again.”

“Even during the alleged economic growth that took place under Gen Musharraf’s rule, not everyone gained. The poor, in particular, actually suffered more,” writes Dr. Burki.

When countries are used as the laboratory to run experiments by powerful institutions, the masses have to face the consequences. The Pakistani masses are paying the price of establishments’ failed experiments since 1958. Even after the ignominious breakup of Pakistan, the establishment did not stop doing its experiments. The creation of a “real leader” was the most recent experiment which was – as expected -- failed miserably.

During the coming decades, the failed experiment would leave significant scars on the social fabric of the nation, in the same way as the long-lasting blisters were inflicted on the society by Zia’s adventurism, which -- even after 25 years of his death -- are festering.