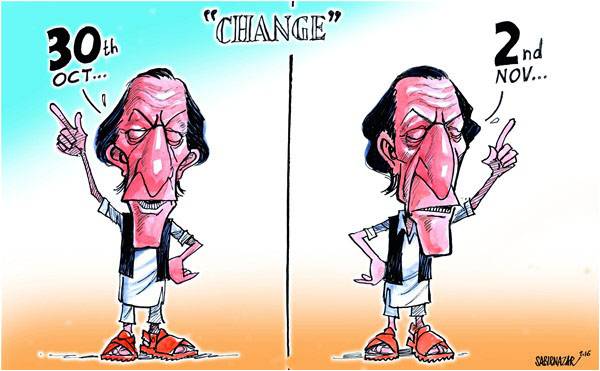

Is some sort of radical “change” in the air?

Imran Khan is touring the Punjab, whipping up anti-Nawaz sentiment and exhorting his supporters to descend on Islamabad on November 2 and “shut it down”. Indeed, he has decided that this is a “now or never” moment for his political career that may be consigned to the wilderness if Nawaz Sharif survives to win the next election in 2018.

The strategy Imran Khan has adopted — ousting an elected government by street power that clashes with the administrative writ of the government and provokes the army to intervene – is neither novel nor new. Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto led a mass movement in 1967-68 against General Ayub Khan and provoked Gen Yahya Khan to intervene. In 1977, the boot was on the other foot when the opposition parties ganged up against Bhutto and provoked General Zia ul Haq to throw him out. In 1993, Benazir Bhutto used the same tactics to effect regime change when the army stepped in to oust Nawaz Sharif. Indeed, Nawaz Sharif did much the same with his “long march” from Lahore to Islamabad in 2009 when he nudged the army to compel President Asif Zardari to restore Iftikhar Chaudhry and his fellow judges so that they could pay back the compliment by hounding the PPP, ousting its prime minister and rendering it impotent at the next elections in 2013, paving the way for Nawaz Sharif’s return to power.

During each such “do-or-die” moment in Pakistan’s history, certain ingredients of success may be identified. First, street protests have to be significantly mass oriented and prolonged to generate a wave of discontent that can engulf the government. Second, the situation has to be primed for violence and bloodshed so that each round of clashes enrages the protestors, evokes public sympathy and spurs them on. Third, for one reason or another, the army leadership must be sufficiently interested or “involved” in wanting to see the back of the regime.

In the current scenario, it seems all these elements are falling into place. Imran has demonstrated his ability to whip up street passions. The four-month long dharna in 2014 and his relentless “road shows” in the last month are evidence of his staying power. Violence, too, has seemingly been injected into the developing situation. The PMLN has alleged that the KPK government has bought the services of disgruntled jihadi elements – Rs 30 crores was earlier dished out to the mother-father of all jihadi and Taliban groups and institutions led by Maulana Sami ul Haq — to inject blood into the movement. And there is no denying a significant breach in civil-military relations of late that shows no sign of being bridged. Does that mean that the end is nigh for Nawaz Sharif?

Not necessarily. Much also depends on how certain countervailing factors can weigh in to the advantage of Nawaz Sharif.

If the government can pre-empt or thwart Imran Khan’s movement to shut down Islamabad by a selective application of controlled force, dispersal and arrests, the “wave” may not materialize. That would give Nawaz time to retire the current army chief who has become a symbol of defiance and appoint someone who may be inclined in his early term to be less aggressive or intrusive. That would take the sting out of the scorpion’s tail. Certainly, we may expect some such announcement to be made sooner rather than later, even as the administration gears up to resist the coming onslaught.

There are two other critical factors. When there is an army intervention in politics to effect regime change, the first assumption is that it is prepared to go the whole hog and impose martial law if its will is thwarted. In other words, it is able and willing to take the “ultimate” step. The second assumption is that the target has been sufficiently softened to compel him to make an appropriate exit without recourse to the “ultimate” step. But in the current situation, there is some doubt about both these assumptions.

Will the current military leadership risk a division in its command when it is on the eve of a major institutional transition to a new leadership? Is the current army chief in an ambitious mood to seize power? Does the current military leadership think it can manage the ship of Pakistan in a sea of regional turbulence, internal divisions and economic distress? Can it cope with the fallout of mass alienation from all parties save one? Equally significantly, will Nawaz Sharif wilt at the first sign of a military intervention rather than stand his ground and dare the military to impose martial law?

The news analysis of the impending political “demise” of Nawaz Sharif in November may or may not be exaggerated. Equally, if it comes to pass, we may or may not shed tears for him. But we will collectively have to share the burden of national tragedy, loss and pain that is inflicted whenever there is martial law in the country.

Imran Khan is touring the Punjab, whipping up anti-Nawaz sentiment and exhorting his supporters to descend on Islamabad on November 2 and “shut it down”. Indeed, he has decided that this is a “now or never” moment for his political career that may be consigned to the wilderness if Nawaz Sharif survives to win the next election in 2018.

The strategy Imran Khan has adopted — ousting an elected government by street power that clashes with the administrative writ of the government and provokes the army to intervene – is neither novel nor new. Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto led a mass movement in 1967-68 against General Ayub Khan and provoked Gen Yahya Khan to intervene. In 1977, the boot was on the other foot when the opposition parties ganged up against Bhutto and provoked General Zia ul Haq to throw him out. In 1993, Benazir Bhutto used the same tactics to effect regime change when the army stepped in to oust Nawaz Sharif. Indeed, Nawaz Sharif did much the same with his “long march” from Lahore to Islamabad in 2009 when he nudged the army to compel President Asif Zardari to restore Iftikhar Chaudhry and his fellow judges so that they could pay back the compliment by hounding the PPP, ousting its prime minister and rendering it impotent at the next elections in 2013, paving the way for Nawaz Sharif’s return to power.

During each such “do-or-die” moment in Pakistan’s history, certain ingredients of success may be identified. First, street protests have to be significantly mass oriented and prolonged to generate a wave of discontent that can engulf the government. Second, the situation has to be primed for violence and bloodshed so that each round of clashes enrages the protestors, evokes public sympathy and spurs them on. Third, for one reason or another, the army leadership must be sufficiently interested or “involved” in wanting to see the back of the regime.

In the current scenario, it seems all these elements are falling into place. Imran has demonstrated his ability to whip up street passions. The four-month long dharna in 2014 and his relentless “road shows” in the last month are evidence of his staying power. Violence, too, has seemingly been injected into the developing situation. The PMLN has alleged that the KPK government has bought the services of disgruntled jihadi elements – Rs 30 crores was earlier dished out to the mother-father of all jihadi and Taliban groups and institutions led by Maulana Sami ul Haq — to inject blood into the movement. And there is no denying a significant breach in civil-military relations of late that shows no sign of being bridged. Does that mean that the end is nigh for Nawaz Sharif?

Not necessarily. Much also depends on how certain countervailing factors can weigh in to the advantage of Nawaz Sharif.

If the government can pre-empt or thwart Imran Khan’s movement to shut down Islamabad by a selective application of controlled force, dispersal and arrests, the “wave” may not materialize. That would give Nawaz time to retire the current army chief who has become a symbol of defiance and appoint someone who may be inclined in his early term to be less aggressive or intrusive. That would take the sting out of the scorpion’s tail. Certainly, we may expect some such announcement to be made sooner rather than later, even as the administration gears up to resist the coming onslaught.

There are two other critical factors. When there is an army intervention in politics to effect regime change, the first assumption is that it is prepared to go the whole hog and impose martial law if its will is thwarted. In other words, it is able and willing to take the “ultimate” step. The second assumption is that the target has been sufficiently softened to compel him to make an appropriate exit without recourse to the “ultimate” step. But in the current situation, there is some doubt about both these assumptions.

Will the current military leadership risk a division in its command when it is on the eve of a major institutional transition to a new leadership? Is the current army chief in an ambitious mood to seize power? Does the current military leadership think it can manage the ship of Pakistan in a sea of regional turbulence, internal divisions and economic distress? Can it cope with the fallout of mass alienation from all parties save one? Equally significantly, will Nawaz Sharif wilt at the first sign of a military intervention rather than stand his ground and dare the military to impose martial law?

The news analysis of the impending political “demise” of Nawaz Sharif in November may or may not be exaggerated. Equally, if it comes to pass, we may or may not shed tears for him. But we will collectively have to share the burden of national tragedy, loss and pain that is inflicted whenever there is martial law in the country.