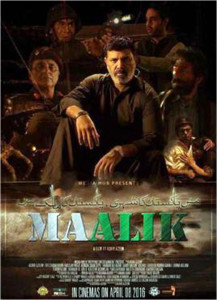

It is everything that defines a Pakistani: confused, in love with the Army and peculiarly patriotic. Maalik, in that sense, is as Pakistani as it gets. This is something Pakistanis should be happy about - or should they?

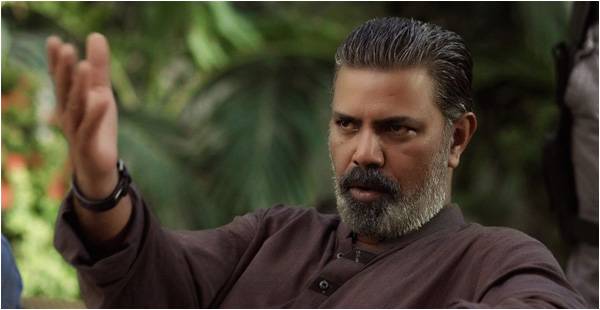

It is everything that defines a Pakistani: confused, in love with the Army and peculiarly patriotic. Maalik, in that sense, is as Pakistani as it gets. This is something Pakistanis should be happy about - or should they?The film - produced, directed and starred in by Ashir Azeem - opens up with the kidnapping of the son of what seems to be a business tycoon, in Karachi. After attempting to contact the authorities to no avail, the businessman contacts a security organisation of a different nature for help - an organisation that goes by the name of “Maalik”. This security organisation specialises in dealing out favours to people who come to them for help, a la Don Corleone. And much like Don Corleone and his Cosa Nostra, it succeeds in achieving what the favour-seekers asked for: extracting the tycoon’s son. However, in return for the service, Maalik’s owner, Major Asad (Ashir Azeem) unlike your average Mafiosi, asks not for money, nor for favour, but for a promise: that should the need arise, the favour-seeker, too, would serve society selflessly.

After resolving the case, Major Asad proceeds to meet his father, Gen. Amjad (Sajid Hassan), who looks about the same age as him (makeup failure) and tells him that he is going to confess something. Soon after, Major Asad goes to the nearby police station and makes a confession: that he has murdered two people (surprised?).

The film snaps to different eras without really explaining why

From this point onward, the film snaps to different eras without really explaining why, leaving much to the intelligence of the viewer. What, in fact, the director and screenplay writer Ashir Azeem attempted to do was to tell the stories of the founders of Maalik in order to explore the reasons that compelled them to form the organisation. Asad himself had lost his wife while serving as a Major in the Army. Late one night, he is summoned for a mission, to which he goes leaving his pregnant wife alone at home. When he returns, he finds out that his wife slipped badly and was in the ICU. When he reaches the hospital, he finds his wife dead (which doesn’t really explain why he chose to fight the evils of society). Luckily, his daughter had survived, and it was to take care of her that he decided to take an early retirement from the Army. Once retired, he and his father decided to establish a private security company called Black Ops Pvt Ltd.

The film then switches to another time frame, sketching out the background of Maalik’s ideologist, Master Mohsin. Master Mohsin (Mohammed Ehteshamuddin) was an idealist and a schoolteacher in a village in Sindh, and was the hardest served by fate: his daughter was raped and murdered by a local feudal lord (Hassan Niazi) against whom Master Mohsin dared to speak openly. On his daughter’s funeral, his wife suffered a heart attack and passed away as well. As if this wasn’t enough, his only son was arrested on charges of murdering his sister. It is in this state that Master Mohsin is forced to move to Karachi, in order to make a living and to escape the wrath of the feudal lord.

In another timeframe, a Pashtun family escapes the Afghan-Soviet War in Afghanistan (should be at some point in the late 1980s) leaving a son behind, who wanted to take part in the jihad against Soviet ‘infidels’. The family relocates to Karachi, where misfortune falls upon them when their eldest daughter is forcefully taken and raped by the fictional Chief Minister of Sindh - the very feudal lord who had murdered Master Mohsin’s daughter (dates don’t really add up). The CM is also the man who Black Ops Pvt Ltd - led by Major Asad - are providing their security services to. And this is how the various scattered stories of the film are merged into one.

In Maalik, the best performances come from the two negative leads of the film. So much for social change

As can be judged by the film’s storyline, Maalik is another one of those films that seeks to bring about social change by discussing social evils out in the open. The intention in making the film was undoubtedly to target and defame the corrupt feudal elite of the country that has been rendering the country hollow since its inception. But what did the film actually achieve?

Producers of films like Maalik often tend to ignore certain bitter truths of our society, and complexities of filmmaking. Our society is made up of individuals who enjoy watching rape scenes in the cinema and dirty dialogues ensuing from them (rest assured, I speak from my own experience here) - therefore including these in our films would do very little to serve the public good. Secondly, when casting for a film, it is best to cast the better actors as the heroes and not the villains.

Unfortunately in the case of Maalik, the best acting performances come from the two negative leads of the film: Hassan Niazi as the corrupt, rapist feudal lord and Adnan Shah Tipu as his right hand man. Both the actors - together with Rashid Farooqui as the corrupt policeman who aids the Sindhi feudal lord’s operations - are seasoned performers and are better known among the common public than all the male leads combined (barring Sajid Hasan and Farhan Ally Agha, who had minor roles). It is true that Ashir Azeem has previously played the male lead in one of PTV’s most popular dramas, Dhuwan, but the generation that remembers that drama vividly - and Azeem’s role in it - is not quite the one that is filling up cinema halls nowadays.

The result? The acts of the negative leads end up becoming more memorable - and, hence, more influential - than those of the heroes. So much for social change.

Secondly, the editing of the film was very choppy and could very easily leave an average filmgoer dumbfounded because of all the switching between various timeframes without any warning. This, together with the very unnatural acting on part of most of the actors rendered Maalik a very average viewing experience, which is especially painful because it had a lot of potential. It would be beneficial to the moviemakers and to Pakistani cinema as a whole if the filmmakers in general and the makers of Maalik in particular would realise that there is a huge difference between having a great idea and actually executing the film to perfection. Of course, it is easier to write a critique than actually producing a good film, however, if critics do not do their jobs - to criticize films, yes - conscientiously, filmmakers would hardly know exactly where they stand in the film market. As for Maalik, it ranks in the lower stratum of the post-revival films churned out by Pakistani production houses.

For the last bit: dear Pakistani filmmakers, filmmaking is a very complex art, and it is best to take all of its various components into due consideration if the desired effect - in the case of Maalik, social change - is to be achieved. Please pull your socks up, the competition is getting tougher. Sincerely, a hopeful critic.

Khadija Mughal lives in Karachi