On my year-long study tour of the United States, many African Americans, when asked about American identity in relation to the white European settlers who landed at Plymouth, would quote Malcolm X, who with his usual sharp wit had quipped: “We didn’t land on Plymouth Rock, Plymouth Rock landed on us.”

The question of identity is causing conflict and controversy across the world. The United States, acknowledged as the world’s oldest democracy, is no exception. Here different narratives collide and produce different leadership models that represent American identity. While the current president Joe Biden and the previous one Donald Trump have come to represent two kinds of irreconcilable American identities there are in fact other identities too. Not only the white settlers have a narrative about American history and culture: The Mexicans, the African Americans and the Native American have a distinct understanding of American history. Nonetheless, until recently the dominant narrative has been that of the White European settlers.

In my study Journey into America: The Challenge of Islam, I had set out to travel the length and breadth of the United States to understand American identity. Accompanied by my dedicated team of researchers, we travelled to some 75 towns and cities and visited 100 mosques. We interviewed hundreds of different kinds of Americans including well-known scholars like Noam Chomsky and Shaykh Hamza Yusuf. At the end of it, we produced a book Journey into America and a documentary film of the same name. The book won the National Book Award, and I was invited to speak about it in the media including The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. Some reviewers spotting the similarity in the foreign provenance of the author compared our study to that of Alexis de Tocqueville’s classic book on America: “this is a must read—a new de Tocqueville on America for the 21st century” (Choice, 2011.) The film was widely shown at film festivals, university campuses and around the world, for example, at the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Melbourne, Australia. Barbara J. Stephenson, the Deputy Chief of Mission at the US Embassy in London, while introducing a special screening of Journey into America at the Embassy, said, “Professor Ahmed is—quite simply—one of the greatest scholars of Islam in the world today[...]for me, Journey into America makes the essential discovery: that you can be an American and a Muslim and it diminishes neither your national nor your religious identity.”

The three American identities

The core idea of Journey into America is that the key to understanding American society and its relationship with its minorities like Muslims can best be explained by appreciating what I defined as the three American identities, which have been in play since the English settlers first arrived in the New World—primordial identity, pluralist identity, and predator identity. Rarely in the social sciences do we note the geometrically neat and schematic matchup between theoretical models and actual communities on the ground and the durability and resilience of these models.

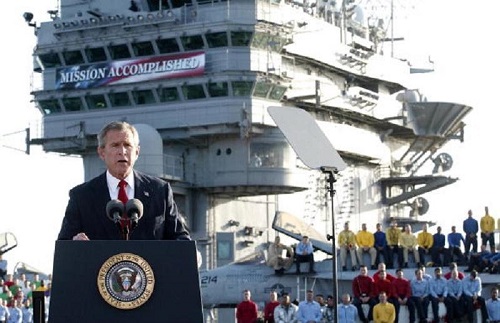

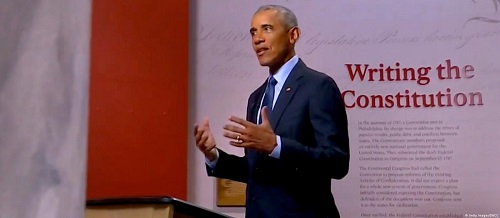

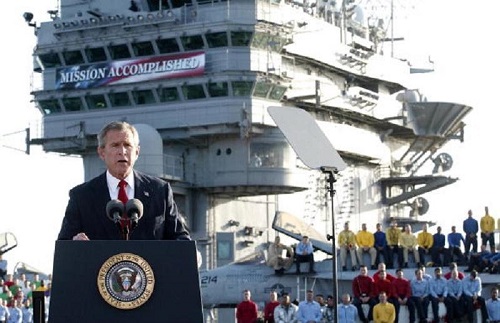

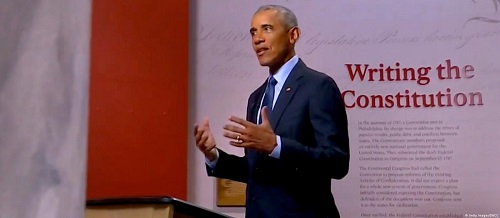

At the risk of gross simplification, one by one, in sequence, we saw the three models in play since the fateful events that followed 9/11—under George W. Bush the primordial identity, with Barack Hussein Obama (and his vice president, and later president, Joseph R. Biden), the pluralist identity, and with Donald J. Trump the predator identity. These models are not watertight and indeed individuals may shift from one to another over time, but they give us a rough and ready image and idea of a certain distinct type of American society. The presidents thus become emblematic of a particular model of American identity. This method can help us make sense of American society since 9/11.

Primordial identity goes back to the landing of the English settlers on the North American continent, best personified by the early settlement at Plymouth: It was unmistakably white in color, English in language and culture, and Protestant in faith. This identity provided the foundation for normative American identity for centuries. The other two identities emerged out of this primordial identity. The American Founding Fathers would personify our second identity that we called pluralist identity. They enshrined Enlightenment-era principles of religious freedom and civil rights and liberties in the founding documents of the nation. It is to be noted, however, that American pluralist identity predates the Founding Fathers to figures such as Roger Williams in New England and the founding of Plymouth. William’s ideas about race, democracy and education were well ahead of his time. The third identity, which I refer to as predator identity, is defined by the often-brutal lengths to which Americans were prepared to go to protect the purity of their ethnic community rooted in primordial identity. Predator identity is characterised by a “zero tolerance” policy towards the “enemy” and perceived threats to the community, and also by a lack of self-reflection and self-analysis – which allows the enemy to be demonised and destroyed.

Predator identity took shape in the early days of white settlement and was focused initially on the Native Americans. At first, the white settlers attempted to convert the Native Americans to Christianity. When Native Americans began to convert, the white settlers shifted the argument to that of color. Even if the Native American became Christian, they argued, their color was still not white. The safety of the Native Americans could not be guaranteed especially in the face of continued conflict as the white population pushed west and seized native land. Predator identity would also focus intently on other minorities such as the African Americans.

One of the Native Americans that we met at Plymouth during fieldwork, and quoted in Journey into America, a Wampanoag, captured this history in a single statistic: “Let me give you a shocking number. Five hundred years ago, we made up 100 percent of what is the United States today. Today we make up 1 percent of the entire population.”

Most models in the social sciences are notoriously unstable, short-lived and unpredictable in their consequences – baffling to those not of the discipline, and in the end perhaps of little value. In our case, however, on the basis of empirical evidence, and with the proper caveats, we can stand by our models, as they have stood the test of time.

While commentators were talking with anxiety about a new kind of authoritarian America emerging, accelerating after the arrival of the coronavirus and in advance of the presidential election, it is also clear that the love of freedom, democracy, pluralism, and strong ideas of human compassion are still valued in the land.

The book also happened to be released at the time of the controversy over the so-called “Ground Zero Mosque,” in which a Muslim group promoting interfaith dialogue announced plans to build a center near the site of the destroyed Twin Towers. There were outlandish fears that Muslims were seeking to impose “sharia law” on Americans. A series of crises developed involving opposition to mosques in places like Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and I was able to discuss these episodes in the context of Journey into America on programs like Anderson Cooper 360 on CNN. It was thus beneficial to have a study like this available to help explain Islam and America to Americans.

Issues of race, colour and religion remain at the heart of the polarised state that America finds itself in today. Indeed, the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police in May 2020, yet another in a sequence of unarmed African Americans killed by often white police officers, proved to be a flashpoint in a racial reckoning that marked the mainstream ascendancy of the Black Lives Matter movement. The movement and the widespread protests that followed shook the nation to its core. The main question we had set out to explore when we started fieldwork, “what does it mean to be American?” which lay at the heart of the ethnography in our study, remains as pertinent as when we first approached the subject. Our ethnography in the meantime has not aged but remains as a valuable source of information about American society, culture and history. It also helps us understand the US today: there is cause and effect at work here and it sets the stage for the coming time.

American identities in play

When America emerged blinking and unsure from the long night of the Coronavirus, it entered a new world with dangerous challenges. It had witnessed with horror the mob attack on Capitol Hill on 6th January 2021. Russia had invaded Ukraine and although its all-out assault had ground to a halt with the redoubtable resilience of the Ukrainians, the danger of escalation with NATO remained high. Relations between the US and China were drifting towards confrontation.

Kevin Rudd, one of the preeminent China experts of the world, published The Avoidable War, and warned that a conflict between the US and China would be “catastrophic.” The historian Niall Ferguson argued that we were already in “Cold War II,” which may well heat up at any moment, and called his book Doom. The US was in danger of falling into the trap of a war on two fronts with two major opponents. Both the US and China, the two giants sitting on top of the world, were wobbling. It was not encouraging for the other nations looking to these two for leadership.

The devastating impact of climate change was also making itself visible on our television screens and in newspaper headlines. The cyclones, hurricanes, typhoons, melting glaciers, flooded cities, droughts, and wildfires illustrated that climate change was a reality. Several nations were already facing severe famine. There were heartbreaking scenes on television of famished fathers in Afghanistan and Somalia describing with choking voices why they had to sell their small daughters. However, the American response to climate change was once again complex and divided. Donald Trump and his supporters dismissed climate change, seeing it as a conspiracy of the “elite” and America’s enemies. Trump claimed, “The concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese in order to make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive.” Climate change was therefore politicised, ensuring that the full urgency of the matter had not yet dawned on the American public.

American society also faced severe internal problems: From 2000 to 2020, the number of female Americans ages 15 to 24 committing suicide rose by 87 percent, with most of the increase occurring after 2007, and the number of suicides by male Americans ages 15 to 24 also rose, but not nearly as starkly. The problem of the police shooting unarmed people has shown no signs of abating—a study released in 2022 showed that nearly one third of all people killed by US police in the past seven years were trying to run away in encounters often starting at traffic stops. Mass shootings also showed no signs of slowing and in 2022 several episodes were marked as American national tragedies. In May 2022, Payton Gendron, an 18-year-old male upset over the “great replacement” of whites, opened fire at a predominantly black supermarket, in Buffalo, NY, shooting 13 and killing 10. He adopted his ideology and murderous plan from Brenton Tarrant, the perpetrator of the 2019 New Zealand Christchurch massacre of Muslims, calling his manifesto, “You Wait for a Signal While Your People Wait for You,” after a section in Tarrant’s manifesto. Both killers cited Anders Breivik, the white supremacist Norwegian terrorist who in 2011 murdered 77 and injured 319 in and around Oslo for their perceived support of Muslim immigration. While Gendron blamed Jews, Muslims, and Latinos for also being “replacers,” he said he targeted black Americans in this particular instance, because “I can’t possibly attack all groups at once so might as well target one.”

In the meantime, the fortunes of the Muslims in America took an upturn. When Trump became US president in 2016, succeeding Barack Obama, his first order was to issue what came to be known as the “Muslim ban,” banning entry of people from several Muslim majority nations into the United States. Trump had first called for this action in 2015 when a candidate, demanding “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States.” Just a few years later, after Joe Biden was elected in 2020, the 2022 midterm elections saw Muslims winning at least 83 seats at the local, state and federal level. “I ran because I wanted to make sure that we had representation in the halls of power,” declared Bangladeshi-American Nabilah Islam, the first Muslim woman and the first South Asian woman to be elected to the Georgia State Senate. Biden himself nominated the first Muslim US federal judge, Zahid Quraishi, the son of Pakistani immigrants, who was confirmed by the Senate in 2021, and Nusrat Jahan Choudhury, a Bangladeshi-American civil rights lawyer, who if confirmed by the Senate would be the first Muslim woman federal judge. Clearly Biden’s America was not Trump’s America.

The Muslim emergence in mainstream American politics, even though overdue and tentative, traced a remarkable trajectory of the community which followed the footsteps of other minorities, as discussed in Journey into America. Commentators noted the historic nature of Muslims becoming federal judges, for example, comparing them to the first Jewish federal judge, Jacob Trieber, who was nominated by President William McKinley and confirmed in 1900.Trieber immigrated to the US at the age of 13 from Prussia and broke the streak of white Christian male federal judges that had endured since 1789.

Immediately after the assault on the Capitol, Washington, D.C. was effectively locked down in advance of Biden’s inauguration, with 25,000 troops deployed, more than were deployed at the time in Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq combined. Soldiers and security forces set up checkpoints across the downtown area and Capitol Hill was referred to as the “Green Zone” after the highly fortified center of government administration in Baghdad. Americans were jarred by the sight of hundreds of troops camped inside the Capitol itself; reportedly the first time since the Civil War that this had occurred.

Respected voices in the country like General Stanley McChrystal, the former US and NATO commander in Afghanistan, warned in the days following the siege of the trials and dangers ahead for the country. McChrystal, who also served as the head of the US Joint Special Operations Command, related what the nation saw in Washington to Iraq and its al Qaeda affiliate, which developed into ISIS. In the case of al Qaeda in Iraq, McChrystal said, “a whole generation of angry Arab youth with very poor prospects followed a powerful leader who promised to take them back in time to a better place, and he led them to embrace an ideology that justified their violence. This is now happening in America.”

For the United States’ top military official General Mark Milley, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff who served under Trump, the president’s effort to steal the election was straight out of “the gospel of the Führer” and was “a Reichstag moment” in keeping with Adolf Hitler’s seizure of power. Trump’s MAGA supporters who flooded Washington, Milley said, were “brownshirts in the streets.”

The Trump era and the 6th of January shook Americans and those around the world who looked to the US as a democratic model. The US was added to the annual list of “backsliding” democracies by the International IDEA thinktank. While the world watched the events of the 6th of January with horror, not long after, in fact almost exactly two years after, Brazilians staged a full-fledged attack on government offices including the congress and presidential palace while challenging the results of the presidential elections.

Americans say, “it could never happen here,” yet we saw it happening here. It should also be noted that while there were pluralist figures like Roger Williams among the early colonists, primordial and predator identity dominated US history for nearly two centuries prior to the Founding Fathers and thus has a longer history than pluralist identity and the democratic system the Founding Fathers introduced. A large-scale poll published in July 2022 carried out by University of California scientists found that one out of every five adults in the US, “equivalent to about 50 million people, believe that political violence is justified at least in some circumstances.” The poll showed that “mistrust and alienation from democratic institutions have reached such a peak that substantial minorities of the American people now endorse violence as a means towards political ends.” In October 2022, David DePape of San Francisco, who had posted QAnon material online and invective against groups including “elites,” Jews, and Muslims, tried to do just this in his attempted murder of Nancy Pelosi’s husband Paul in their family home, which he had broken into looking for Nancy Pelosi.

These are ominous signs that adherents of predator identity may be increasingly willing to resort to violence in the “protection” and “defense” of the “community” as they see it. In the aftermath of the Pelosi attack, the African American Congressman Jim Clyburn, a civil rights leader in the 1960s and senior ranking House Democrat, captured these fears when he said that the US “is on track to repeat what happened in Germany” in the 1930s.

American identity in Biden’s America

While Biden’s critics accused him of being old and infirm, in his first days as president he moved with the alacrity of a young man in a hurry. Within days of moving into the Oval Office, he took a vigorous broom to the rubble left behind by Trump and in short order he removed the controversial Muslim ban, amended the immigration procedures, appointed John Kerry as the climate czar, and saw the rejoining of the US with the nations working to alleviate the impact of climate change in accordance with the Paris climate agreement. Then, he managed to pass a truly gigantic coronavirus relief bill of $1.9 trillion without a single Republican assisting him. Perhaps most momentous of all, he made available millions of vaccines and committed to injecting every American.

Yes, there was no denying that pluralist America had come roaring back. The election of Biden’s vice president Kamala Harris marked the first time in history that a woman, and that too with an identity that included her black Jamaican father and Indian mother, had reached the high office. Of course, predator identity did not let her get away without scorn being poured on the pronunciation of her name. In fact, Biden promised the president’s “most diverse cabinet” in US history, and the cabinet was indeed historic in its pluralist nature: in addition to Vice President Harris, it featured the first female secretary of the treasury, Janet Yellen, the first black secretary of defense, Lloyd Austin, the first openly gay cabinet secretary, Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg, and the first Native American cabinet secretary, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland.

Yet while pluralist America was strong, clear and back in power, its position remained wobbly as predator identity had never conceded its position. On the contrary, its leader, Trump, despite being banned from just about all major social media platforms for inciting violence, continued to use his foghorn to advocate for the politics he had instituted and had been rejected by Biden and the new administration. The fact remained that a large percentage of Americans remained loyal to President Trump. Recall that not one Republican Senator supported the initial coronavirus relief bill and they had refused to convict Trump during his second impeachment for inciting the Capitol siege and riot. They likewise refused to vote to establish an independent commission to investigate the riot. In the face of logic, demands for unity in facing the national challenge of the pandemic, and the desire to right the wrongs of the past in the aftermath of the Capitol attack, the Republicans dug in their heels and many still proclaimed that the election was unfairly won by Biden.

For anyone who might have thought that support for Trump had ebbed within the party post-presidency, the six-foot golden statue of Trump put on display at the Conservative Political Action Conference in Orlando, Florida, in February 2021, should have demonstrated the hold that he continued to have. Among the conference’s most popular attractions, it was a visual representation and metaphor of the fact that, despite beating the drum of their Judeo-Christian character, supporters were ignoring basic exhortations not to worship golden calves, or golden anything.

For anyone who might have thought that support for Trump had ebbed within the party post-presidency, the six-foot golden statue of Trump put on display at the Conservative Political Action Conference in Orlando, Florida, in February 2021, should have demonstrated the hold that he continued to have. Among the conference’s most popular attractions, it was a visual representation and metaphor of the fact that, despite beating the drum of their Judeo-Christian character, supporters were ignoring basic exhortations not to worship golden calves, or golden anything.

Revisiting pluralist identity is a reminder of the unique and long-lasting vision that the Founding Fathers gave the United States as represented by Jefferson’s phrase “all men are created equal,” that has consistently proved as an inspiration to those seeking human equality in all its forms. It was also a time to reflect on the nation’s past and its future. Much remained unresolved and uncertain as America continued to grapple with questions of its own identity, its place in the world, its domestic and foreign policies, the place of minorities such as Muslims in its society, and how to address the problems it faced. What we could predict was that the contours of our three identities would remain strong and dynamic.

The question of identity is causing conflict and controversy across the world. The United States, acknowledged as the world’s oldest democracy, is no exception. Here different narratives collide and produce different leadership models that represent American identity. While the current president Joe Biden and the previous one Donald Trump have come to represent two kinds of irreconcilable American identities there are in fact other identities too. Not only the white settlers have a narrative about American history and culture: The Mexicans, the African Americans and the Native American have a distinct understanding of American history. Nonetheless, until recently the dominant narrative has been that of the White European settlers.

In my study Journey into America: The Challenge of Islam, I had set out to travel the length and breadth of the United States to understand American identity. Accompanied by my dedicated team of researchers, we travelled to some 75 towns and cities and visited 100 mosques. We interviewed hundreds of different kinds of Americans including well-known scholars like Noam Chomsky and Shaykh Hamza Yusuf. At the end of it, we produced a book Journey into America and a documentary film of the same name. The book won the National Book Award, and I was invited to speak about it in the media including The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. Some reviewers spotting the similarity in the foreign provenance of the author compared our study to that of Alexis de Tocqueville’s classic book on America: “this is a must read—a new de Tocqueville on America for the 21st century” (Choice, 2011.) The film was widely shown at film festivals, university campuses and around the world, for example, at the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Melbourne, Australia. Barbara J. Stephenson, the Deputy Chief of Mission at the US Embassy in London, while introducing a special screening of Journey into America at the Embassy, said, “Professor Ahmed is—quite simply—one of the greatest scholars of Islam in the world today[...]for me, Journey into America makes the essential discovery: that you can be an American and a Muslim and it diminishes neither your national nor your religious identity.”

The three American identities

The core idea of Journey into America is that the key to understanding American society and its relationship with its minorities like Muslims can best be explained by appreciating what I defined as the three American identities, which have been in play since the English settlers first arrived in the New World—primordial identity, pluralist identity, and predator identity. Rarely in the social sciences do we note the geometrically neat and schematic matchup between theoretical models and actual communities on the ground and the durability and resilience of these models.

At the risk of gross simplification, one by one, in sequence, we saw the three models in play since the fateful events that followed 9/11—under George W. Bush the primordial identity, with Barack Hussein Obama (and his vice president, and later president, Joseph R. Biden), the pluralist identity, and with Donald J. Trump the predator identity. These models are not watertight and indeed individuals may shift from one to another over time, but they give us a rough and ready image and idea of a certain distinct type of American society. The presidents thus become emblematic of a particular model of American identity. This method can help us make sense of American society since 9/11.

Primordial identity goes back to the landing of the English settlers on the North American continent, best personified by the early settlement at Plymouth: It was unmistakably white in color, English in language and culture, and Protestant in faith. This identity provided the foundation for normative American identity for centuries. The other two identities emerged out of this primordial identity. The American Founding Fathers would personify our second identity that we called pluralist identity. They enshrined Enlightenment-era principles of religious freedom and civil rights and liberties in the founding documents of the nation. It is to be noted, however, that American pluralist identity predates the Founding Fathers to figures such as Roger Williams in New England and the founding of Plymouth. William’s ideas about race, democracy and education were well ahead of his time. The third identity, which I refer to as predator identity, is defined by the often-brutal lengths to which Americans were prepared to go to protect the purity of their ethnic community rooted in primordial identity. Predator identity is characterised by a “zero tolerance” policy towards the “enemy” and perceived threats to the community, and also by a lack of self-reflection and self-analysis – which allows the enemy to be demonised and destroyed.

Predator identity took shape in the early days of white settlement and was focused initially on the Native Americans. At first, the white settlers attempted to convert the Native Americans to Christianity. When Native Americans began to convert, the white settlers shifted the argument to that of color. Even if the Native American became Christian, they argued, their color was still not white. The safety of the Native Americans could not be guaranteed especially in the face of continued conflict as the white population pushed west and seized native land. Predator identity would also focus intently on other minorities such as the African Americans.

One of the Native Americans that we met at Plymouth during fieldwork, and quoted in Journey into America, a Wampanoag, captured this history in a single statistic: “Let me give you a shocking number. Five hundred years ago, we made up 100 percent of what is the United States today. Today we make up 1 percent of the entire population.”

The key to understanding American society and its relationship with its minorities like Muslims can best be explained by appreciating what I defined as the three American identities, which have been in play since the English settlers first arrived in the New World

Most models in the social sciences are notoriously unstable, short-lived and unpredictable in their consequences – baffling to those not of the discipline, and in the end perhaps of little value. In our case, however, on the basis of empirical evidence, and with the proper caveats, we can stand by our models, as they have stood the test of time.

While commentators were talking with anxiety about a new kind of authoritarian America emerging, accelerating after the arrival of the coronavirus and in advance of the presidential election, it is also clear that the love of freedom, democracy, pluralism, and strong ideas of human compassion are still valued in the land.

The book also happened to be released at the time of the controversy over the so-called “Ground Zero Mosque,” in which a Muslim group promoting interfaith dialogue announced plans to build a center near the site of the destroyed Twin Towers. There were outlandish fears that Muslims were seeking to impose “sharia law” on Americans. A series of crises developed involving opposition to mosques in places like Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and I was able to discuss these episodes in the context of Journey into America on programs like Anderson Cooper 360 on CNN. It was thus beneficial to have a study like this available to help explain Islam and America to Americans.

Issues of race, colour and religion remain at the heart of the polarised state that America finds itself in today. Indeed, the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police in May 2020, yet another in a sequence of unarmed African Americans killed by often white police officers, proved to be a flashpoint in a racial reckoning that marked the mainstream ascendancy of the Black Lives Matter movement. The movement and the widespread protests that followed shook the nation to its core. The main question we had set out to explore when we started fieldwork, “what does it mean to be American?” which lay at the heart of the ethnography in our study, remains as pertinent as when we first approached the subject. Our ethnography in the meantime has not aged but remains as a valuable source of information about American society, culture and history. It also helps us understand the US today: there is cause and effect at work here and it sets the stage for the coming time.

American identities in play

When America emerged blinking and unsure from the long night of the Coronavirus, it entered a new world with dangerous challenges. It had witnessed with horror the mob attack on Capitol Hill on 6th January 2021. Russia had invaded Ukraine and although its all-out assault had ground to a halt with the redoubtable resilience of the Ukrainians, the danger of escalation with NATO remained high. Relations between the US and China were drifting towards confrontation.

Kevin Rudd, one of the preeminent China experts of the world, published The Avoidable War, and warned that a conflict between the US and China would be “catastrophic.” The historian Niall Ferguson argued that we were already in “Cold War II,” which may well heat up at any moment, and called his book Doom. The US was in danger of falling into the trap of a war on two fronts with two major opponents. Both the US and China, the two giants sitting on top of the world, were wobbling. It was not encouraging for the other nations looking to these two for leadership.

The devastating impact of climate change was also making itself visible on our television screens and in newspaper headlines. The cyclones, hurricanes, typhoons, melting glaciers, flooded cities, droughts, and wildfires illustrated that climate change was a reality. Several nations were already facing severe famine. There were heartbreaking scenes on television of famished fathers in Afghanistan and Somalia describing with choking voices why they had to sell their small daughters. However, the American response to climate change was once again complex and divided. Donald Trump and his supporters dismissed climate change, seeing it as a conspiracy of the “elite” and America’s enemies. Trump claimed, “The concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese in order to make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive.” Climate change was therefore politicised, ensuring that the full urgency of the matter had not yet dawned on the American public.

There are ominous signs that adherents of predator identity may be increasingly willing to resort to violence in the “protection” and “defense” of the “community” as they see it

American society also faced severe internal problems: From 2000 to 2020, the number of female Americans ages 15 to 24 committing suicide rose by 87 percent, with most of the increase occurring after 2007, and the number of suicides by male Americans ages 15 to 24 also rose, but not nearly as starkly. The problem of the police shooting unarmed people has shown no signs of abating—a study released in 2022 showed that nearly one third of all people killed by US police in the past seven years were trying to run away in encounters often starting at traffic stops. Mass shootings also showed no signs of slowing and in 2022 several episodes were marked as American national tragedies. In May 2022, Payton Gendron, an 18-year-old male upset over the “great replacement” of whites, opened fire at a predominantly black supermarket, in Buffalo, NY, shooting 13 and killing 10. He adopted his ideology and murderous plan from Brenton Tarrant, the perpetrator of the 2019 New Zealand Christchurch massacre of Muslims, calling his manifesto, “You Wait for a Signal While Your People Wait for You,” after a section in Tarrant’s manifesto. Both killers cited Anders Breivik, the white supremacist Norwegian terrorist who in 2011 murdered 77 and injured 319 in and around Oslo for their perceived support of Muslim immigration. While Gendron blamed Jews, Muslims, and Latinos for also being “replacers,” he said he targeted black Americans in this particular instance, because “I can’t possibly attack all groups at once so might as well target one.”

In the meantime, the fortunes of the Muslims in America took an upturn. When Trump became US president in 2016, succeeding Barack Obama, his first order was to issue what came to be known as the “Muslim ban,” banning entry of people from several Muslim majority nations into the United States. Trump had first called for this action in 2015 when a candidate, demanding “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States.” Just a few years later, after Joe Biden was elected in 2020, the 2022 midterm elections saw Muslims winning at least 83 seats at the local, state and federal level. “I ran because I wanted to make sure that we had representation in the halls of power,” declared Bangladeshi-American Nabilah Islam, the first Muslim woman and the first South Asian woman to be elected to the Georgia State Senate. Biden himself nominated the first Muslim US federal judge, Zahid Quraishi, the son of Pakistani immigrants, who was confirmed by the Senate in 2021, and Nusrat Jahan Choudhury, a Bangladeshi-American civil rights lawyer, who if confirmed by the Senate would be the first Muslim woman federal judge. Clearly Biden’s America was not Trump’s America.

The Muslim emergence in mainstream American politics, even though overdue and tentative, traced a remarkable trajectory of the community which followed the footsteps of other minorities, as discussed in Journey into America. Commentators noted the historic nature of Muslims becoming federal judges, for example, comparing them to the first Jewish federal judge, Jacob Trieber, who was nominated by President William McKinley and confirmed in 1900.Trieber immigrated to the US at the age of 13 from Prussia and broke the streak of white Christian male federal judges that had endured since 1789.

Immediately after the assault on the Capitol, Washington, D.C. was effectively locked down in advance of Biden’s inauguration, with 25,000 troops deployed, more than were deployed at the time in Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq combined. Soldiers and security forces set up checkpoints across the downtown area and Capitol Hill was referred to as the “Green Zone” after the highly fortified center of government administration in Baghdad. Americans were jarred by the sight of hundreds of troops camped inside the Capitol itself; reportedly the first time since the Civil War that this had occurred.

Respected voices in the country like General Stanley McChrystal, the former US and NATO commander in Afghanistan, warned in the days following the siege of the trials and dangers ahead for the country. McChrystal, who also served as the head of the US Joint Special Operations Command, related what the nation saw in Washington to Iraq and its al Qaeda affiliate, which developed into ISIS. In the case of al Qaeda in Iraq, McChrystal said, “a whole generation of angry Arab youth with very poor prospects followed a powerful leader who promised to take them back in time to a better place, and he led them to embrace an ideology that justified their violence. This is now happening in America.”

For the United States’ top military official General Mark Milley, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff who served under Trump, the president’s effort to steal the election was straight out of “the gospel of the Führer” and was “a Reichstag moment” in keeping with Adolf Hitler’s seizure of power. Trump’s MAGA supporters who flooded Washington, Milley said, were “brownshirts in the streets.”

The Trump era and the 6th of January shook Americans and those around the world who looked to the US as a democratic model. The US was added to the annual list of “backsliding” democracies by the International IDEA thinktank. While the world watched the events of the 6th of January with horror, not long after, in fact almost exactly two years after, Brazilians staged a full-fledged attack on government offices including the congress and presidential palace while challenging the results of the presidential elections.

For anyone who might have thought that support for Trump had ebbed within the party post-presidency, the six-foot golden statue of Trump put on display at the Conservative Political Action Conference in Orlando, Florida, in February 2021, should have demonstrated the hold that he continued to have

Americans say, “it could never happen here,” yet we saw it happening here. It should also be noted that while there were pluralist figures like Roger Williams among the early colonists, primordial and predator identity dominated US history for nearly two centuries prior to the Founding Fathers and thus has a longer history than pluralist identity and the democratic system the Founding Fathers introduced. A large-scale poll published in July 2022 carried out by University of California scientists found that one out of every five adults in the US, “equivalent to about 50 million people, believe that political violence is justified at least in some circumstances.” The poll showed that “mistrust and alienation from democratic institutions have reached such a peak that substantial minorities of the American people now endorse violence as a means towards political ends.” In October 2022, David DePape of San Francisco, who had posted QAnon material online and invective against groups including “elites,” Jews, and Muslims, tried to do just this in his attempted murder of Nancy Pelosi’s husband Paul in their family home, which he had broken into looking for Nancy Pelosi.

These are ominous signs that adherents of predator identity may be increasingly willing to resort to violence in the “protection” and “defense” of the “community” as they see it. In the aftermath of the Pelosi attack, the African American Congressman Jim Clyburn, a civil rights leader in the 1960s and senior ranking House Democrat, captured these fears when he said that the US “is on track to repeat what happened in Germany” in the 1930s.

American identity in Biden’s America

While Biden’s critics accused him of being old and infirm, in his first days as president he moved with the alacrity of a young man in a hurry. Within days of moving into the Oval Office, he took a vigorous broom to the rubble left behind by Trump and in short order he removed the controversial Muslim ban, amended the immigration procedures, appointed John Kerry as the climate czar, and saw the rejoining of the US with the nations working to alleviate the impact of climate change in accordance with the Paris climate agreement. Then, he managed to pass a truly gigantic coronavirus relief bill of $1.9 trillion without a single Republican assisting him. Perhaps most momentous of all, he made available millions of vaccines and committed to injecting every American.

Yes, there was no denying that pluralist America had come roaring back. The election of Biden’s vice president Kamala Harris marked the first time in history that a woman, and that too with an identity that included her black Jamaican father and Indian mother, had reached the high office. Of course, predator identity did not let her get away without scorn being poured on the pronunciation of her name. In fact, Biden promised the president’s “most diverse cabinet” in US history, and the cabinet was indeed historic in its pluralist nature: in addition to Vice President Harris, it featured the first female secretary of the treasury, Janet Yellen, the first black secretary of defense, Lloyd Austin, the first openly gay cabinet secretary, Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg, and the first Native American cabinet secretary, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland.

Yet while pluralist America was strong, clear and back in power, its position remained wobbly as predator identity had never conceded its position. On the contrary, its leader, Trump, despite being banned from just about all major social media platforms for inciting violence, continued to use his foghorn to advocate for the politics he had instituted and had been rejected by Biden and the new administration. The fact remained that a large percentage of Americans remained loyal to President Trump. Recall that not one Republican Senator supported the initial coronavirus relief bill and they had refused to convict Trump during his second impeachment for inciting the Capitol siege and riot. They likewise refused to vote to establish an independent commission to investigate the riot. In the face of logic, demands for unity in facing the national challenge of the pandemic, and the desire to right the wrongs of the past in the aftermath of the Capitol attack, the Republicans dug in their heels and many still proclaimed that the election was unfairly won by Biden.

For anyone who might have thought that support for Trump had ebbed within the party post-presidency, the six-foot golden statue of Trump put on display at the Conservative Political Action Conference in Orlando, Florida, in February 2021, should have demonstrated the hold that he continued to have. Among the conference’s most popular attractions, it was a visual representation and metaphor of the fact that, despite beating the drum of their Judeo-Christian character, supporters were ignoring basic exhortations not to worship golden calves, or golden anything.

For anyone who might have thought that support for Trump had ebbed within the party post-presidency, the six-foot golden statue of Trump put on display at the Conservative Political Action Conference in Orlando, Florida, in February 2021, should have demonstrated the hold that he continued to have. Among the conference’s most popular attractions, it was a visual representation and metaphor of the fact that, despite beating the drum of their Judeo-Christian character, supporters were ignoring basic exhortations not to worship golden calves, or golden anything.Revisiting pluralist identity is a reminder of the unique and long-lasting vision that the Founding Fathers gave the United States as represented by Jefferson’s phrase “all men are created equal,” that has consistently proved as an inspiration to those seeking human equality in all its forms. It was also a time to reflect on the nation’s past and its future. Much remained unresolved and uncertain as America continued to grapple with questions of its own identity, its place in the world, its domestic and foreign policies, the place of minorities such as Muslims in its society, and how to address the problems it faced. What we could predict was that the contours of our three identities would remain strong and dynamic.