My annual visits to Peshawar are a mixed bag. I deliver lectures at my alma matter Khyber Medical College and a few other institutions, visit the haunts of my childhood and adolescence, call upon a few of my surviving teachers, and visit friends and family to condole a death or to offer my congratulations on a marriage that has taken place in the intervening year. My mother used to keep a list of folks who had died since my last visit, and the marriages that had taken place. With mother’s passing, my younger sister Beego lets me know the friends and family I must visit.

Muzzamal Shah was a distant cousin of ours, who lived in one of Peshawar city’s neighbourhoods. A few months earlier, his young daughter had died of kidney disease in her mid-thirties. I went to offer my condolences.

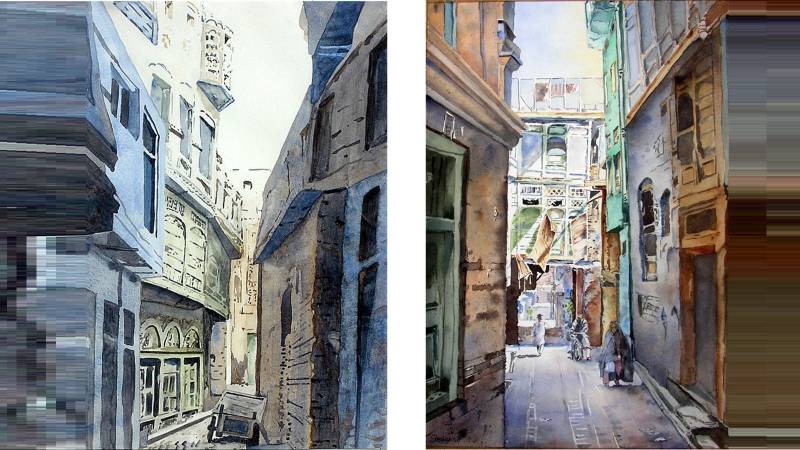

The old city of Peshawar is a maze of narrow serpentine alleys, where the houses have common walls and in some places, it is hard to tell the exact location of the dwelling one wishes to locate. Often one has to ask directions while standing a few steps away from the house. Google or Siri would give up locating a house in this medieval town.

Once I had located the house, I rattled the latch on the faded-green wooden door. After a few moments, someone pulled the rope from upstairs to open the door trap. I stepped into the dark foyer and announced my arrival. My cousin came running down the stairs, gave me an affectionate hug, and asked me to follow him up the stairs.

Muzzamal Shah was a widower, having lost his wife to a brain haemorrhage a number of years earlier. In the tiny house, he lived with his daughter and his son and his wife. In his advancing age, his unmarried daughter looked after him. The fathers in that part of the world or should I say all over the world, rely more on daughters than married sons in their twilight years. And now he felt alone and adrift.

We sat cross-legged on the carpeted floor and went through the pleasantries. He asked about the well-being of my family in America. I asked about his other two married sons and two married daughters. But it was the recent loss of his daughter that had preoccupied him since her death.

We raised our hands in prayers for the salvation of his daughter and concluded with a passage from the Quran that says, “We have all come from Him and unto Him shall we return.” His daughter-in-law brought in a tea tray and cookies. As I greeted her, the man asked me if I would mind looking at the medical reports of his deceased daughter. “Of course,” I said.

I wondered if the outcome would have been different if she had stayed with one physician. Her death could have been postponed by a short duration, but the die was cast

He brought a thick file of medical reports and a bunch of X-rays, each enclosed in fading yellow paper, and placed the file in front of me.

The only medical records that exist in most of Pakistan are the prescription slips that list a patient’s name, age and name of prescribed medicines. Occasionally the doctor would write the diagnosis on the prescription slip. To reconstruct a medical history, one has to put the prescription slips and lab reports in chronological order. Added to the confusion are prescriptions from many different doctors. The story is seldom coherent or complete.

It took me some time to put the pieces together. It seems his daughter had been seeing doctors for over three years, for vague complaints that, in due course, became symptoms of chronic kidney disease. At the time, kidney dialysis was not available in Peshawar. The physicians prescribed whatever medicines were available, but the disease pursued a slow, downhill course.

There is an unhealthy pattern in how physicians approach patients and their diseases in some third world countries. After seeing a prescription from another physician, most physicians, in a game of one-upmanship, go ahead and change the treatment plan and prescribe different medicines. Sometimes this behaviour ends in disastrous results. I wondered if the outcome would have been different if she had stayed with one physician. Her death could have been postponed by a short duration, but the die was cast. Very few physicians have the moral courage to endorse the treatment plan of the previous physician.

The family also pursued other treatments, including visiting the tombs of saints and holy men, in the hope that somehow the disease course would change due to divine intervention, and she would be cured. But there was no escape from the inevitable. Towards the end, regular medicines, unconventional remedies and prayers could not stop the relentless deterioration of her kidneys.

All through the process of reconstructing a coherent disease profile of the young woman, the father kept looking at me expectantly. I could have told him that some of the doctors had mismanaged his daughter’s disease. But in a country where malpractice is rampant, there is really no accountability. Egregious acts of medical malpractice are either ignored by the authorities or in case of an inquiry, the men and women in white coats cover the mistakes of their colleagues.

I told my cousin that her disease was of such a nature that nothing could have been done. It was, I emphasised, the will of God, and we all are helpless in these situations. He seemed resigned to the conclusion I presented to him.

After a while I begged the family’s leave and left.