So many artists today base their works on issues of social consciousness. One such issue is that of enforced disappearances, whose vivid descriptions we read about in the newspapers almost daily. This is a worldwide phenomenon, and according to Amina Masood Janjua, Chairperson of the group Defence of Human Rights Pakistan, there are over 5,000 reported cases of enforced disappearance in this country - with no known allegations against the victims.

From Karachi’s Chawkandi Gallery, concerning Ramzan Jafri’s current exhibition, titled “Depictions of Loss,” we hear that he centres his work around all those unnamed and suppressed victims who have gone missing, disappeared mysteriously or are brutally persecuted - leaving behind only a trail of memories. And Ramzan himself asserts, “My country in general and my clan in particular are constant victims of atrocities based either on sectarianism or on extremism. I have witnessed thousands of innocent people being killed in the name of religion. In fact, in a terrorist attack on the Hazara community at Alamdar Road in Quetta, he witnessed the death of a cousin and friends. This has influenced his recent art works deeply.

In fact, his roots are in the famous Bamiyan area of Afghanistan, but due to sustained persecution of his Hazara people, his family migrated to Quetta before the 1947 Partition. Ramzan was, thus, born and brought up in Quetta.

“Moving to Lahore has made life a bit easier,” he says. “At least I can go out freely, without having to identify myself at check-posts every 10 to 15 minutes.”

As he was born into a family of craftsmen, he became interested in fine arts, and after his course at NCA Lahore, he graduated as MFA (Hons.), majoring in miniature painting. Calligraphy was also a part of his course, and for a time he was an assistant teacher of this art at NCA, later teaching miniature work at the Mushtaq Ahmed Gumani Institute of Traditional Art, Lahore

“My aim,” he explains, “is to expose the reality and inner beauty of things. There is this concept of appearance vs reality. The colour palette, rusting threads, distorted shapes and spoiled materials are all a portrayal of the premature and untimely decay that I have observed. I concentrate on the reality that is, not on what it should be.”

His work and his words bring to mind he etchings and prints of German artist Otto Dix, who recently exhibited at V.M. Gallery and was witness to all the violence that unfolded before his eyes.

Jafri has taken part in many exhibitions, both nationally and internationally, group and solo, and has found his work “welcomed with an open heart in the world of art.”

The visual language of his art is derived from his own experience of violent incidents. The prominent visuals in his art, i.e. fabric, bukrams, aprons and bones, are elements that he chose from what he saw at the sites of these events. Throughout much of human history, bones have been associated not with death, but with life. In many cultures, people actually believe that bones are the seat of the vital principle, or even of the soul. As the locus of life, they believe, they have mystical powers ranging from cures and divination to birth and rebirth. The most important and widely held belief is that bones can be reanimated and are essential to rebirth, especially in northern Eurasia and even amongst the Aboriginal people of Australia, while the bones of animals are often credited with an aura of sanctity. In Christianity, meanwhile, major churches and cathedrals have been built over the graves of martyrs to house their mortal remains, i.e. bones.

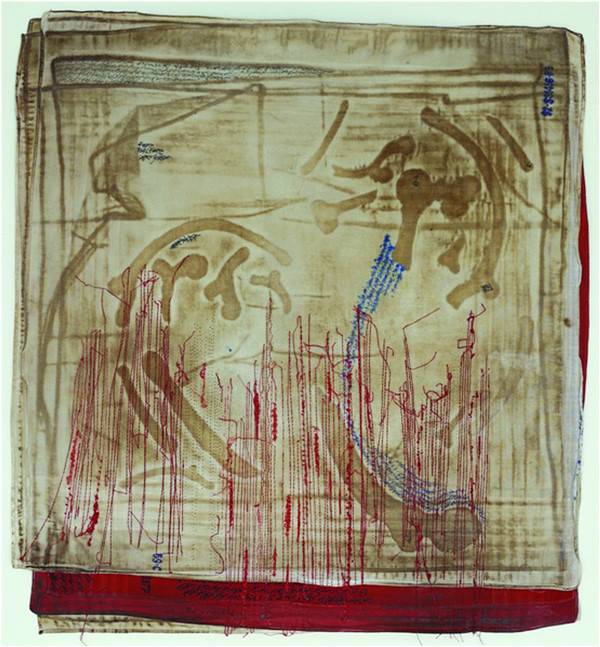

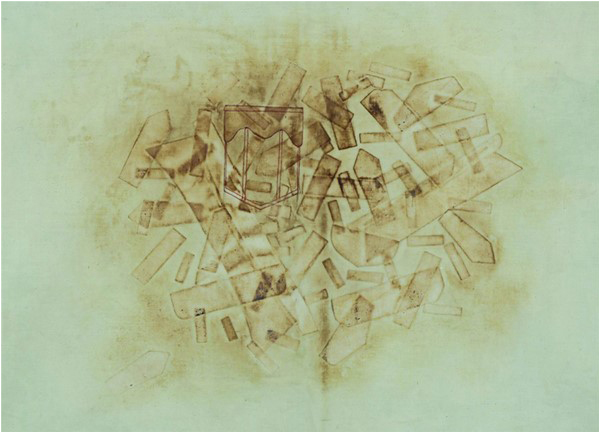

As was already mentioned, Ramazan’s aim is to bring out the inner beauty of things, and looking at his works, despite their origin in ethnic violence, one may well be impressed by the beauty that he as a miniaturist has presented. There is a sense of design and symmetry in them, though his method is certainly practical. He glues layers of bukram onto cloth as a base, and uses an electric iron to cause burns, resulting in the burnt tones of the surface. The red thread illuminates these elements of memory and serves as a metaphor for the blood spilt during the violence. Bukram, by the way, is a stiff cotton cloth with a loose weave. If it is soaked in wheat starch paste, and dried, it can be used to create a durable, firm fabric.

To take a case in point, his picture No. 10 is an example of the use of red thread to symbolize blood. There is symmetry in the pattern formed by these threads, and in fact in the whole composition, with the careful layout of the bones and the positioning of the bukram and other layers beneath the picture, while the red bukram emphasizes the presence of blood.

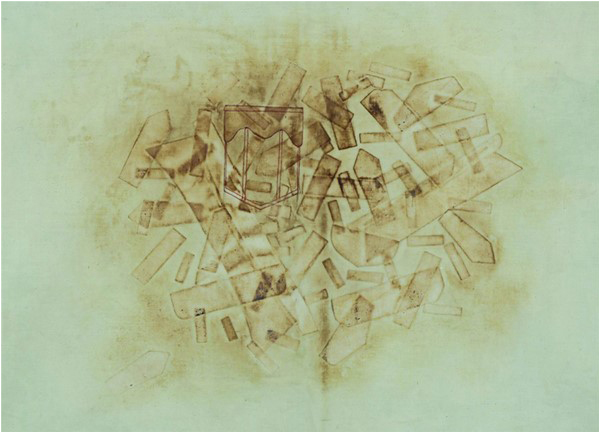

In his No. 7, once more we see beauty emerging out of tragedy. This time the pieces that make up this picture are attractively arranged - mostly in three groups, with curving lines. From a distance, at first glance the subject looks like the Tree of Life, but actually the artist has presented scraps of wood or concrete, signifying demolition during a deadly attack. The life in this piece comes, of course, from the heart of Ramzan. And seeing him work thoughtfully in the videos that are part of the exhibition, we can understand that just as his creations are a part of him, so is he a part of his creations.

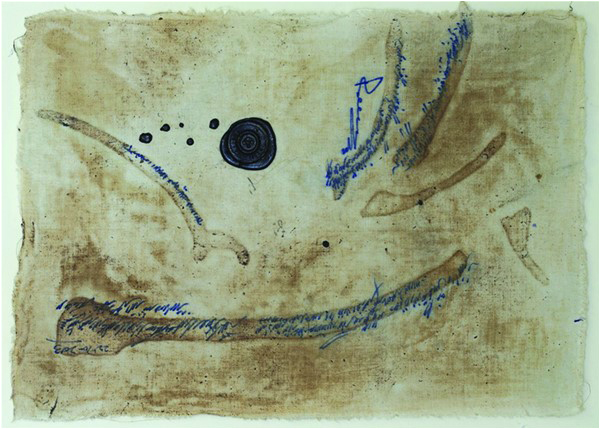

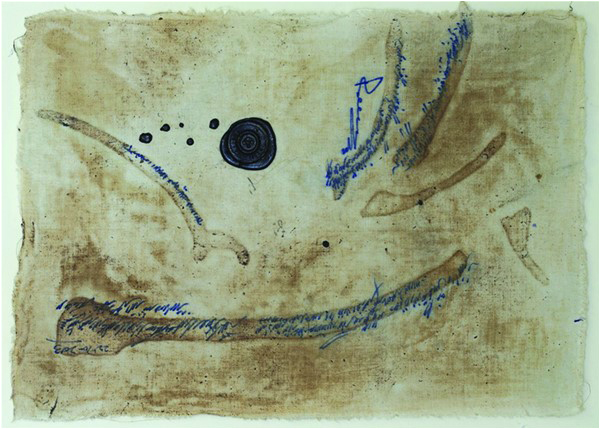

To see or create beauty from the site of brutality is quite an extraordinary achievement. In a couple of pieces -15 and 5 in particular - there are just a few bones with much writing here and there. And adding to the effect there are red or black spots signifying blood.

The writing in a number of these works is about incidents of terrorism that Ramzan has seen. It is not legible, but is included, he explains, as a means of making a more poetic image, and to relate to social issues. His intention is to show not only the incidents, but also the serial numbers and so on of the missing people. But if the viewer cannot read it, then it remains a mystery locked up in the heart of the artist.

An interesting variation is given in Number 11, a free composition where a number of separate elements have been shown. Firstly, over much of the picture there is a tangle of the red thread that signifies blood, and this time it looks rather like barbed wire, while the ominous lines of black thread suggest imprisonment. In some cases the black thread is used to portray shells from larger weapons, and hacksaws, which can be used to break into or out of a place. There are one or two similar pieces in the exhibition, but in this one there is a feeling of completeness. The artist has used a lighter touch, and the composition is busy with the variety of objects, but there is a little positive space here and there to avoid a cramped feeling.

In his acclaimed novel Red Birds Mohammed Hanif asks, “What are people if not the sum total of their memories?”

And it is haunting memories, beautifully presented, that make up Ramzan Jafri’s unusual exhibition.

From Karachi’s Chawkandi Gallery, concerning Ramzan Jafri’s current exhibition, titled “Depictions of Loss,” we hear that he centres his work around all those unnamed and suppressed victims who have gone missing, disappeared mysteriously or are brutally persecuted - leaving behind only a trail of memories. And Ramzan himself asserts, “My country in general and my clan in particular are constant victims of atrocities based either on sectarianism or on extremism. I have witnessed thousands of innocent people being killed in the name of religion. In fact, in a terrorist attack on the Hazara community at Alamdar Road in Quetta, he witnessed the death of a cousin and friends. This has influenced his recent art works deeply.

In fact, his roots are in the famous Bamiyan area of Afghanistan, but due to sustained persecution of his Hazara people, his family migrated to Quetta before the 1947 Partition. Ramzan was, thus, born and brought up in Quetta.

“Moving to Lahore has made life a bit easier,” he says. “At least I can go out freely, without having to identify myself at check-posts every 10 to 15 minutes.”

As he was born into a family of craftsmen, he became interested in fine arts, and after his course at NCA Lahore, he graduated as MFA (Hons.), majoring in miniature painting. Calligraphy was also a part of his course, and for a time he was an assistant teacher of this art at NCA, later teaching miniature work at the Mushtaq Ahmed Gumani Institute of Traditional Art, Lahore

“My aim,” he explains, “is to expose the reality and inner beauty of things. There is this concept of appearance vs reality. The colour palette, rusting threads, distorted shapes and spoiled materials are all a portrayal of the premature and untimely decay that I have observed. I concentrate on the reality that is, not on what it should be.”

His work and his words bring to mind he etchings and prints of German artist Otto Dix, who recently exhibited at V.M. Gallery and was witness to all the violence that unfolded before his eyes.

Jafri has taken part in many exhibitions, both nationally and internationally, group and solo, and has found his work “welcomed with an open heart in the world of art.”

The visual language of his art is derived from his own experience of violent incidents. The prominent visuals in his art, i.e. fabric, bukrams, aprons and bones, are elements that he chose from what he saw at the sites of these events. Throughout much of human history, bones have been associated not with death, but with life. In many cultures, people actually believe that bones are the seat of the vital principle, or even of the soul. As the locus of life, they believe, they have mystical powers ranging from cures and divination to birth and rebirth. The most important and widely held belief is that bones can be reanimated and are essential to rebirth, especially in northern Eurasia and even amongst the Aboriginal people of Australia, while the bones of animals are often credited with an aura of sanctity. In Christianity, meanwhile, major churches and cathedrals have been built over the graves of martyrs to house their mortal remains, i.e. bones.

The prominent visuals in his art, i.e. fabric, bukrams, aprons and bones, are elements that he chose from what he saw at the sites of violent events

As was already mentioned, Ramazan’s aim is to bring out the inner beauty of things, and looking at his works, despite their origin in ethnic violence, one may well be impressed by the beauty that he as a miniaturist has presented. There is a sense of design and symmetry in them, though his method is certainly practical. He glues layers of bukram onto cloth as a base, and uses an electric iron to cause burns, resulting in the burnt tones of the surface. The red thread illuminates these elements of memory and serves as a metaphor for the blood spilt during the violence. Bukram, by the way, is a stiff cotton cloth with a loose weave. If it is soaked in wheat starch paste, and dried, it can be used to create a durable, firm fabric.

To take a case in point, his picture No. 10 is an example of the use of red thread to symbolize blood. There is symmetry in the pattern formed by these threads, and in fact in the whole composition, with the careful layout of the bones and the positioning of the bukram and other layers beneath the picture, while the red bukram emphasizes the presence of blood.

In his No. 7, once more we see beauty emerging out of tragedy. This time the pieces that make up this picture are attractively arranged - mostly in three groups, with curving lines. From a distance, at first glance the subject looks like the Tree of Life, but actually the artist has presented scraps of wood or concrete, signifying demolition during a deadly attack. The life in this piece comes, of course, from the heart of Ramzan. And seeing him work thoughtfully in the videos that are part of the exhibition, we can understand that just as his creations are a part of him, so is he a part of his creations.

To see or create beauty from the site of brutality is quite an extraordinary achievement. In a couple of pieces -15 and 5 in particular - there are just a few bones with much writing here and there. And adding to the effect there are red or black spots signifying blood.

The writing in a number of these works is about incidents of terrorism that Ramzan has seen. It is not legible, but is included, he explains, as a means of making a more poetic image, and to relate to social issues. His intention is to show not only the incidents, but also the serial numbers and so on of the missing people. But if the viewer cannot read it, then it remains a mystery locked up in the heart of the artist.

An interesting variation is given in Number 11, a free composition where a number of separate elements have been shown. Firstly, over much of the picture there is a tangle of the red thread that signifies blood, and this time it looks rather like barbed wire, while the ominous lines of black thread suggest imprisonment. In some cases the black thread is used to portray shells from larger weapons, and hacksaws, which can be used to break into or out of a place. There are one or two similar pieces in the exhibition, but in this one there is a feeling of completeness. The artist has used a lighter touch, and the composition is busy with the variety of objects, but there is a little positive space here and there to avoid a cramped feeling.

In his acclaimed novel Red Birds Mohammed Hanif asks, “What are people if not the sum total of their memories?”

And it is haunting memories, beautifully presented, that make up Ramzan Jafri’s unusual exhibition.