Prime Minister Imran Khan’s prediction of an incoming “good government” in Kabul has compounded the anxiety of the Afghan government that was nervously watching the talks between the United States and the Taliban progress in Doha.

Speaking in Bajaur three days after US and Taliban concluded their longest ever round of talks, the prime minister, in an attempt to reassure the people of the erstwhile tribal areas bordering Afghanistan, unwittingly went a little too far. “A good government will be established in Afghanistan, a government where all Afghans will be represented. The war will end and peace will be established there,” the prime minister said.

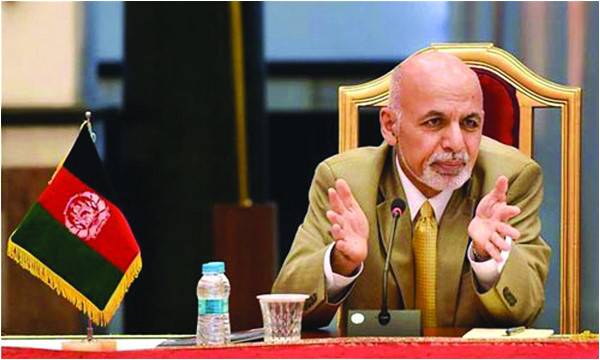

The Afghan government protested over these comments and described them as “a flagrant interference in its internal affairs.” A more blunt reaction to the developments, if not PM Khan’s remarks per se, and one that reflected the intensity of frustration of Ghani’s government, came from Afghan National Security Adviser Amb Hamdullah Mohib. He hit out at US Special Envoy for Afghan Peace and Reconciliation Amb Zalmay Khalilzad, saying he feared that US, by going ahead with a peace process that did not include Kabul, was effectively “delegitimising the Afghan government and weakening it and at the same time elevating the Taliban.”

The remarks did come as a surprise for Washington, which in its immediate reaction stopped all contacts with the Afghan NSA, who was visiting US. Mohib’s remarks forced some introspection in the White House. President Trump later held a classified meeting with his national security team comprising among others Vice President Mike Pence, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, CIA Director Gina Haspel and national security adviser John Bolton, in the Pentagon. The meeting was reportedly meant to review the situation in Afghanistan.

The US may have rightly assessed that Afghan government may be of little help with the peace process because of its capacity as well as inhibitions, but that it cannot afford to alienate Kabul at any cost. Soon after refusing to meet with Mohib, Amb Khalilzad reached out to Afghanistan’s envoy in Washington, Amb Roya Rahmani, to underline that the peace initiative “is neither an easy nor straight path we are walking. To stay on track, it is of utmost importance we continue to walk it together.”

Amb Rahmani also had a meeting with senior White House aide Lisa Curtis to emphasise that the progress made over the past 18 years had to be preserved.

Meanwhile, the talks in Doha, which began on February 25 and ended on March 12, have four basic elements: counter-terrorism assurances by Taliban that Afghan soil, if they return to power, would not be allowed to be used against US or any of its allies; troop withdrawal; intra-Afghan dialogue; and a comprehensive ceasefire. This agenda was agreed back in January and now both sides, after the conclusion of the last round of talks, had moved a step closer to a deal by drafting agreements on counter-terrorism assurances and troop withdrawal.

Amb Khalilzad himself said, “There is no final agreement until everything is agreed.” Although the details of the discussions have not been revealed by either side, it is clear that there are still differences over the definition of terrorism, the timeline for the withdrawal of the US and Coalition forces and the nature and scope of any future US military presence in Afghanistan.

Persisting differences over the definition of terrorism were highlighted by a recent statement by Secretary Pompeo, in which he labelled Taliban as “terrorists.” Similarly, the US is eyeing a two-year timeframe for withdrawal and retaining a small military formation in Afghanistan for protection of its diplomatic mission and other counter-terrorism actions, whereas Taliban have so far been calling for a full withdrawal.

Currently, there are approximately 14,000 US troops deployed in Afghanistan. Additionally, there are roughly 9000 troops from coalition partners there as well. The withdrawal, if and when it happens, would be by all coalition partners, not just US. Amb Khalizad said, “We came together. We will coordinate adjustments in our presence together. And if we leave, we will leave together.”

However, amidst all this uncertainty, the main question is whether the upcoming Afghan presidential elections will go ahead as planned. Is a transition set up being planned to govern the war-torn country till the next political dispensation is in place, in case the elections do not happen on schedule? If a transition government is imminent, then what will be its composition and would the Taliban be part of it? These are the questions that are making Ghani’s government and its allies in Afghanistan restless. PM Khan’s statement about an impending good government only served to accentuate those worries.

Peace in Afghanistan after 18 long years of war is desired by everyone but President Ghani and his colleagues, already feeling excluded from the peace initiative, feel a disadvantage ahead of the polls because of some ground realities: the Taliban having ascendancy on the battlefield and the government’s calls for a seat on the negotiating table as a stakeholder in the process are going unheard. These are definitely not good optics for someone seeking re-election. n

The writer is a senior researcher at Islamabad Policy Institute. She can be reached at mamoona.rubab@ipipk.org

Speaking in Bajaur three days after US and Taliban concluded their longest ever round of talks, the prime minister, in an attempt to reassure the people of the erstwhile tribal areas bordering Afghanistan, unwittingly went a little too far. “A good government will be established in Afghanistan, a government where all Afghans will be represented. The war will end and peace will be established there,” the prime minister said.

The Afghan government protested over these comments and described them as “a flagrant interference in its internal affairs.” A more blunt reaction to the developments, if not PM Khan’s remarks per se, and one that reflected the intensity of frustration of Ghani’s government, came from Afghan National Security Adviser Amb Hamdullah Mohib. He hit out at US Special Envoy for Afghan Peace and Reconciliation Amb Zalmay Khalilzad, saying he feared that US, by going ahead with a peace process that did not include Kabul, was effectively “delegitimising the Afghan government and weakening it and at the same time elevating the Taliban.”

The remarks did come as a surprise for Washington, which in its immediate reaction stopped all contacts with the Afghan NSA, who was visiting US. Mohib’s remarks forced some introspection in the White House. President Trump later held a classified meeting with his national security team comprising among others Vice President Mike Pence, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, CIA Director Gina Haspel and national security adviser John Bolton, in the Pentagon. The meeting was reportedly meant to review the situation in Afghanistan.

The main question is whether the upcoming Afghan presidential elections will go ahead as planned

The US may have rightly assessed that Afghan government may be of little help with the peace process because of its capacity as well as inhibitions, but that it cannot afford to alienate Kabul at any cost. Soon after refusing to meet with Mohib, Amb Khalilzad reached out to Afghanistan’s envoy in Washington, Amb Roya Rahmani, to underline that the peace initiative “is neither an easy nor straight path we are walking. To stay on track, it is of utmost importance we continue to walk it together.”

Amb Rahmani also had a meeting with senior White House aide Lisa Curtis to emphasise that the progress made over the past 18 years had to be preserved.

Meanwhile, the talks in Doha, which began on February 25 and ended on March 12, have four basic elements: counter-terrorism assurances by Taliban that Afghan soil, if they return to power, would not be allowed to be used against US or any of its allies; troop withdrawal; intra-Afghan dialogue; and a comprehensive ceasefire. This agenda was agreed back in January and now both sides, after the conclusion of the last round of talks, had moved a step closer to a deal by drafting agreements on counter-terrorism assurances and troop withdrawal.

Amb Khalilzad himself said, “There is no final agreement until everything is agreed.” Although the details of the discussions have not been revealed by either side, it is clear that there are still differences over the definition of terrorism, the timeline for the withdrawal of the US and Coalition forces and the nature and scope of any future US military presence in Afghanistan.

Persisting differences over the definition of terrorism were highlighted by a recent statement by Secretary Pompeo, in which he labelled Taliban as “terrorists.” Similarly, the US is eyeing a two-year timeframe for withdrawal and retaining a small military formation in Afghanistan for protection of its diplomatic mission and other counter-terrorism actions, whereas Taliban have so far been calling for a full withdrawal.

Currently, there are approximately 14,000 US troops deployed in Afghanistan. Additionally, there are roughly 9000 troops from coalition partners there as well. The withdrawal, if and when it happens, would be by all coalition partners, not just US. Amb Khalizad said, “We came together. We will coordinate adjustments in our presence together. And if we leave, we will leave together.”

However, amidst all this uncertainty, the main question is whether the upcoming Afghan presidential elections will go ahead as planned. Is a transition set up being planned to govern the war-torn country till the next political dispensation is in place, in case the elections do not happen on schedule? If a transition government is imminent, then what will be its composition and would the Taliban be part of it? These are the questions that are making Ghani’s government and its allies in Afghanistan restless. PM Khan’s statement about an impending good government only served to accentuate those worries.

Peace in Afghanistan after 18 long years of war is desired by everyone but President Ghani and his colleagues, already feeling excluded from the peace initiative, feel a disadvantage ahead of the polls because of some ground realities: the Taliban having ascendancy on the battlefield and the government’s calls for a seat on the negotiating table as a stakeholder in the process are going unheard. These are definitely not good optics for someone seeking re-election. n

The writer is a senior researcher at Islamabad Policy Institute. She can be reached at mamoona.rubab@ipipk.org