The second Peshawar Literature Festival (PLF 2023) featured a fascinating session titled: "Representation in Colonial Discourse: The Racial Image and Spatial Image of the Pukhtoons." Students and other people interested in the history and identity of the Pashtun community attended the session in large numbers. The Q&A portion of the session ended up being so emotionally charged and captivating that the moderators struggled to end it on time, leaving the audience members' questions unanswered.

Pashtuns have historically been denigrated by Western writers as "savages," "barbaric" warriors, and "uncivilised" people. Most of those authors belonged to the occupying coloniser's military or political wing.

Since local voices were either unavailable or not heard internationally, the only way the outside world could understand the Pashtuns was through the racialised historical narratives that those Western military and political "historians" had exported.

Thus, Elphinstone, who personally participated in the conflict with the Pashtuns, wrote his memoir The 1842 Retreat from Kabul, also known as the "Slaughter of Elphinstone's Army," during the First Anglo-Afghan War. Elphinstone's account of the events, which includes a derogatory depiction of the Pashtun people that persists to this day, was understandably influenced by his own experiences of defeat.

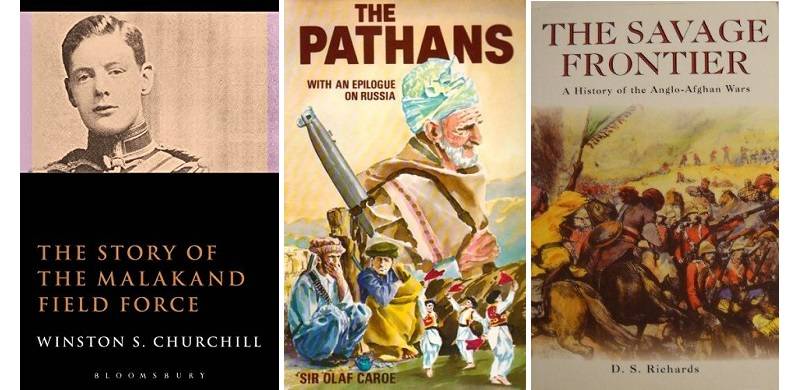

D.S. Richards, another Western author, released his account of the Anglo-Afghan wars in 1990 under the title The Savage Frontier. Since the book's title says it all up front, his interpretation of the events is self-explanatory.

Among the flock of Western writers who wrote memoirs-cum-histories about Pashtuns, the person who went the extra mile was the statesman and Nobel Laureate Winston Churchill, who has been hailed by his fellow civilized men as "one of the greatest figures of the twentieth century,". Churchill was among the first generation of "civilized" writers who “introduced” Pashtuns to the outside world. How did he introduce them, do you ask? Consider the following extract:

“The [Pashtun] tribesmen are among the most miserable and brutal creatures on earth. Their intelligence only enables them to be more cruel [sic], more dangerous, and more destructible than wild beasts. […] I find it impossible to come to any other conclusion than that, in the proportion that these valleys are purged from the pernicious vermin that infest them, so will the happiness of humanity be increased, and the progress of mankind accelerated.”

Winston Churchill wrote this dispatch for The Daily Telegraph on the morning of 22 September 1897, during the British campaign in present-day Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa.

In his autobiography, My Early Life, this “civilized” man recalls the 1897 battle with Pashtun tribes in Mohmand. Churchill refers to the British as "the dominant race" in that passage, but he describes the brutal treatment of the Pashtun people with such pride and jubilation that his conscience is completely unaffected. Churchill does not call that treatment “savagery” because it was carried out by the “dominant race.”

He brags about one of his victories against Pashtuns as follows: “We proceeded systematically, village by village, and we destroyed the houses, filled up the wells, blew down the towers, cut down the great shady trees, burned the crops and broke the reservoirs in punitive devastation […] and every tribesman caught was speared or cut down at once.”

He wrote to a friend in September 1897: “After today we begin to burn villages, everyone. And all who resist will be killed without quarter. The Mohmands need a lesson, and there is no doubt we are a very cruel people.”

For better or worse, Churchill's name is inscribed in large letters on a stone piquet that overlooks the Swat River in Chakdara, a town close to Malakand, where he reportedly wrote some of his dispatches demonising the Pashtuns.

James W. Spain, another ‘civilized’ writer on the history of Pashtuns, wrote in 1961. “Small wonder that it is so. All the classic ingredients of strife are there […] They [the Pashtuns] are warrior tribesmen bonded together by a common language and literature […] and a superb contempt for all peoples outside their own highly developed clan system. To a man, they are orthodox and militant followers of Islam."

The discourse of the “savage Pathan” had been initiated by the colonial masters and carried out, knowingly or unknowingly, by the present-day producers of knowledge and discourse at home as well. The local voices were either too low to be heard or sank silently into the loud sounds of gunfire and bomb blasts.

The discourse of the “savage Pathan” had been initiated by the colonial masters and carried out, knowingly or unknowingly, by the present-day producers of knowledge and discourse at home as well. The local voices were either too low to be heard or sank silently into the loud sounds of gunfire and bomb blasts.

Most "historians" of the Pashtuns were non-Pashtuns, ranging from Olaf Caroe's The Pathans, published in 1958 (Caroe was a British administrator working for the Indian Civil Service), to Tilak Devasher's The Pashtuns: A Contested History, published in 2022 (an Indian government servant). Perhaps the first Pashtun voice to be heard on a worldwide scale was that of Abu Bakr Siddique, who published The Pashtun Question in 2013.

From 2011 to 2021, other cities held a variety of literary festivals, but Peshawar was groaning under the weight of imposed identity crises and the aftershocks of foreign wars.

However, the efforts of a few sincere individuals paid off, and PLF was launched in 2022. As compared to last year, PLF-2023 expanded both in terms of days (five days as compared to the previous three) and venues (three hours as compared to one. The number of visitors who marked their attendance on the first day was around 1100. Interestingly, not only was the entry free for the visitors, but there were no charges for setting up any bookstalls either.

Numerous banners and posters that were hung throughout the venue bore the names, photographs and brief biographies of local intellectuals who had contributed in any way to the field of literature. Besides, the theme of the second edition of PLF was “Globalising the Local.”

The festival will be expanded to the South and North of K.P. the following year, according to its organisers.

Seeing the weary community engaged with words and ideas, one couldn’t help but be reminded of the well-known African saying that Chinua Achebe has referenced in Things Fall Apart in 1958. It says, “Until the lion learns how to write, the tale of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”

We had the impression that the lion was learning how to craft its own version of the tale as we watched Pashtuns converse about words, narratives and discourse in a land known as a playground for conflicts.

Pashtuns have historically been denigrated by Western writers as "savages," "barbaric" warriors, and "uncivilised" people. Most of those authors belonged to the occupying coloniser's military or political wing.

Since local voices were either unavailable or not heard internationally, the only way the outside world could understand the Pashtuns was through the racialised historical narratives that those Western military and political "historians" had exported.

Thus, Elphinstone, who personally participated in the conflict with the Pashtuns, wrote his memoir The 1842 Retreat from Kabul, also known as the "Slaughter of Elphinstone's Army," during the First Anglo-Afghan War. Elphinstone's account of the events, which includes a derogatory depiction of the Pashtun people that persists to this day, was understandably influenced by his own experiences of defeat.

D.S. Richards, another Western author, released his account of the Anglo-Afghan wars in 1990 under the title The Savage Frontier. Since the book's title says it all up front, his interpretation of the events is self-explanatory.

Among the flock of Western writers who wrote memoirs-cum-histories about Pashtuns, the person who went the extra mile was the statesman and Nobel Laureate Winston Churchill, who has been hailed by his fellow civilized men as "one of the greatest figures of the twentieth century,". Churchill was among the first generation of "civilized" writers who “introduced” Pashtuns to the outside world. How did he introduce them, do you ask? Consider the following extract:

“The [Pashtun] tribesmen are among the most miserable and brutal creatures on earth. Their intelligence only enables them to be more cruel [sic], more dangerous, and more destructible than wild beasts. […] I find it impossible to come to any other conclusion than that, in the proportion that these valleys are purged from the pernicious vermin that infest them, so will the happiness of humanity be increased, and the progress of mankind accelerated.”

Winston Churchill wrote this dispatch for The Daily Telegraph on the morning of 22 September 1897, during the British campaign in present-day Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa.

Most "historians" of the Pashtuns were non-Pashtuns, ranging from Olaf Caroe's The Pathans, published in 1958 (Caroe was a British administrator working for the Indian Civil Service), to Tilak Devasher's The Pashtuns: A Contested History, published in 2022 (an Indian government servant)

In his autobiography, My Early Life, this “civilized” man recalls the 1897 battle with Pashtun tribes in Mohmand. Churchill refers to the British as "the dominant race" in that passage, but he describes the brutal treatment of the Pashtun people with such pride and jubilation that his conscience is completely unaffected. Churchill does not call that treatment “savagery” because it was carried out by the “dominant race.”

He brags about one of his victories against Pashtuns as follows: “We proceeded systematically, village by village, and we destroyed the houses, filled up the wells, blew down the towers, cut down the great shady trees, burned the crops and broke the reservoirs in punitive devastation […] and every tribesman caught was speared or cut down at once.”

He wrote to a friend in September 1897: “After today we begin to burn villages, everyone. And all who resist will be killed without quarter. The Mohmands need a lesson, and there is no doubt we are a very cruel people.”

For better or worse, Churchill's name is inscribed in large letters on a stone piquet that overlooks the Swat River in Chakdara, a town close to Malakand, where he reportedly wrote some of his dispatches demonising the Pashtuns.

James W. Spain, another ‘civilized’ writer on the history of Pashtuns, wrote in 1961. “Small wonder that it is so. All the classic ingredients of strife are there […] They [the Pashtuns] are warrior tribesmen bonded together by a common language and literature […] and a superb contempt for all peoples outside their own highly developed clan system. To a man, they are orthodox and militant followers of Islam."

The discourse of the “savage Pathan” had been initiated by the colonial masters and carried out, knowingly or unknowingly, by the present-day producers of knowledge and discourse at home as well. The local voices were either too low to be heard or sank silently into the loud sounds of gunfire and bomb blasts.

The discourse of the “savage Pathan” had been initiated by the colonial masters and carried out, knowingly or unknowingly, by the present-day producers of knowledge and discourse at home as well. The local voices were either too low to be heard or sank silently into the loud sounds of gunfire and bomb blasts.Most "historians" of the Pashtuns were non-Pashtuns, ranging from Olaf Caroe's The Pathans, published in 1958 (Caroe was a British administrator working for the Indian Civil Service), to Tilak Devasher's The Pashtuns: A Contested History, published in 2022 (an Indian government servant). Perhaps the first Pashtun voice to be heard on a worldwide scale was that of Abu Bakr Siddique, who published The Pashtun Question in 2013.

From 2011 to 2021, other cities held a variety of literary festivals, but Peshawar was groaning under the weight of imposed identity crises and the aftershocks of foreign wars.

However, the efforts of a few sincere individuals paid off, and PLF was launched in 2022. As compared to last year, PLF-2023 expanded both in terms of days (five days as compared to the previous three) and venues (three hours as compared to one. The number of visitors who marked their attendance on the first day was around 1100. Interestingly, not only was the entry free for the visitors, but there were no charges for setting up any bookstalls either.

Numerous banners and posters that were hung throughout the venue bore the names, photographs and brief biographies of local intellectuals who had contributed in any way to the field of literature. Besides, the theme of the second edition of PLF was “Globalising the Local.”

The festival will be expanded to the South and North of K.P. the following year, according to its organisers.

Seeing the weary community engaged with words and ideas, one couldn’t help but be reminded of the well-known African saying that Chinua Achebe has referenced in Things Fall Apart in 1958. It says, “Until the lion learns how to write, the tale of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”

We had the impression that the lion was learning how to craft its own version of the tale as we watched Pashtuns converse about words, narratives and discourse in a land known as a playground for conflicts.