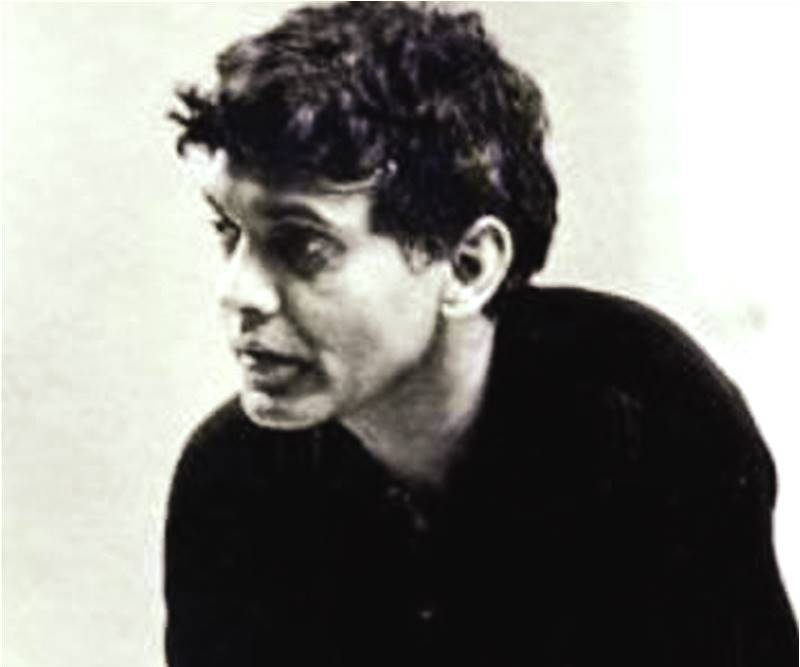

May 11 marks 21 years since my uncle Eqbal Ahmad (1933-1999), a much loved public intellectual and friend of humanity, passed away at the relatively young age of 66 years. Much more than just a relation, Eqbal was my guardian and mentor, someone I looked upto. I miss him terribly.

But my purpose in writing today is not just to eulogize him or even to recount special moments I spent with him. Rather, it is to pose a question to his friends and admirers. This is a question that struck me when I tried to emulate Eqbal in my own small way by writing about vexing issues in Pakistan in such areas as water resources, public transport, health, education, justice and the economy. I was not alone in this. And along with writing, we would also come out in the streets on these issues. After five years I realized that verbal and street activism did not make an iota of change and that things actually went from bad to worse. In fact, the futility of my efforts is evident from the title of my last article: “I Give Up”.

Eqbal Ahmad was a most prescient scholar and an astute analyst of world events. He had an uncanny knack of predicting the destructive outcomes of actions by powerful countries or ruthless regimes. For example, if we read Eqbal’s predictions on the consequences of the proxy war the CIA was carrying out against the Soviets in Afghanistan one may be forgiven for thinking that he wrote it after the events, so incisive were his insights.

So here is the question: Why was nothing done to prevent the outcome that Eqbal predicted in that instance, or that others have predicted in other cases? A related and, in some ways, even more important question is this: What should be the role of a public intellectual? Is it sufficient to diagnose a problem correctly or is it necessary to combine the analysis with political activism to stop the predicted outcome? Also, what forms should such activism take? Why does it seem that to find successful examples of political activism one has to go as far back as the Vietnam war that ended in 1975?

The constant warnings by Eqbal (and later by his friend, Noam Chomsky) on the problematic Middle East policies of the West fell flat. Those who agreed with their analysis were unable to mount any significant resistance against the perpetrators of bad policies. It reminds one of the Chronicle of a Death Foretold story by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, in which everyone in a town knows that a plan is underway to kill a man. Even the man to be killed knew about it and yet the murder takes place.

Hence the perplexing question: Is it possible to stop a certain flow of events of history that has a negative outcome even if someone wise predicts it? What is the responsibility of the intellectual, or of those who have seen the proverbial light? A pessimist may answer that nothing will happen to change the outcome because it is in human nature to seek power and material wealth no matter what the cost. If such a sad conclusion is correct, then the red flags raised by the very few will never result in course correction.

I would, of course, have loved to put this question to Eqbal himself since he was not just a thinker but also an activist in his own right. My only clue about how he might have answered comes from what he liked to say when asked about his outlook on the right way to approach the problem of abuse of power, and injustice: quoting the Nobel prize winning French dramatist, Romain Rolland, he would respond: Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will. Eqbal lived and died by this maxim.

But my purpose in writing today is not just to eulogize him or even to recount special moments I spent with him. Rather, it is to pose a question to his friends and admirers. This is a question that struck me when I tried to emulate Eqbal in my own small way by writing about vexing issues in Pakistan in such areas as water resources, public transport, health, education, justice and the economy. I was not alone in this. And along with writing, we would also come out in the streets on these issues. After five years I realized that verbal and street activism did not make an iota of change and that things actually went from bad to worse. In fact, the futility of my efforts is evident from the title of my last article: “I Give Up”.

Eqbal Ahmad was a most prescient scholar and an astute analyst of world events. He had an uncanny knack of predicting the destructive outcomes of actions by powerful countries or ruthless regimes. For example, if we read Eqbal’s predictions on the consequences of the proxy war the CIA was carrying out against the Soviets in Afghanistan one may be forgiven for thinking that he wrote it after the events, so incisive were his insights.

So here is the question: Why was nothing done to prevent the outcome that Eqbal predicted in that instance, or that others have predicted in other cases? A related and, in some ways, even more important question is this: What should be the role of a public intellectual? Is it sufficient to diagnose a problem correctly or is it necessary to combine the analysis with political activism to stop the predicted outcome? Also, what forms should such activism take? Why does it seem that to find successful examples of political activism one has to go as far back as the Vietnam war that ended in 1975?

The constant warnings by Eqbal (and later by his friend, Noam Chomsky) on the problematic Middle East policies of the West fell flat. Those who agreed with their analysis were unable to mount any significant resistance against the perpetrators of bad policies. It reminds one of the Chronicle of a Death Foretold story by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, in which everyone in a town knows that a plan is underway to kill a man. Even the man to be killed knew about it and yet the murder takes place.

Why does it seem that to find successful examples of political activism one has to go as far back as the Vietnam war that ended in 1975?

Hence the perplexing question: Is it possible to stop a certain flow of events of history that has a negative outcome even if someone wise predicts it? What is the responsibility of the intellectual, or of those who have seen the proverbial light? A pessimist may answer that nothing will happen to change the outcome because it is in human nature to seek power and material wealth no matter what the cost. If such a sad conclusion is correct, then the red flags raised by the very few will never result in course correction.

I would, of course, have loved to put this question to Eqbal himself since he was not just a thinker but also an activist in his own right. My only clue about how he might have answered comes from what he liked to say when asked about his outlook on the right way to approach the problem of abuse of power, and injustice: quoting the Nobel prize winning French dramatist, Romain Rolland, he would respond: Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will. Eqbal lived and died by this maxim.