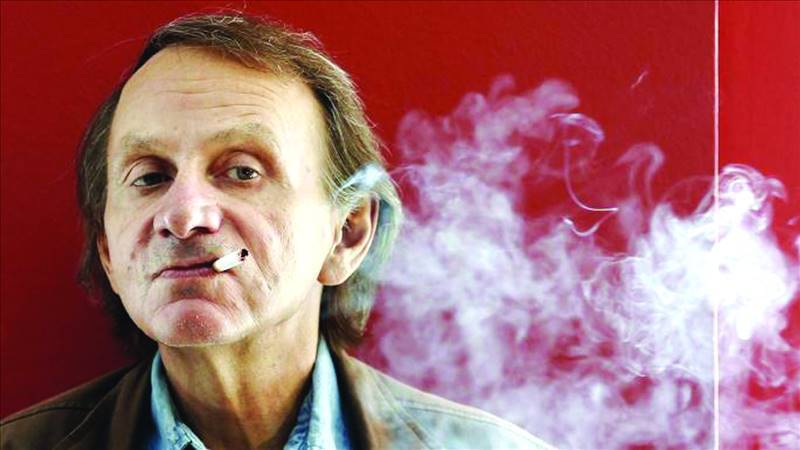

Michel Houellebecq (b. 1956), who writes in French, may well be the most admired and the most reviled author in the West today. He has been branded as a misogynist, a misanthrope, a racist and an Islamophobe but has also been hailed as the most creative and significant writer since Albert Camus. France awarded him its highest honour, the Legion of Honour, as well as the prestigious Prix Goncourt for his novel The Map and the Territory (2010).

Houellebecq has produced seven novels to date, the most recent one being Serotonin, published in 2019. All his books have roused controversy but four have taken the literary world by storm and resulted in bouquets and brickbats showered on the writer: The Atomized (also published as The Elementary Particles, 1998), Platform (2001), The Possibility of an Island (2005), and Submission (2015).

Most of Houellebecq’s novels are set in the present, the near future and the distant future. His fiction is infused with elements of science fiction, presenting an alternative vision of human existence. Addressing this, he notes in H.P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life, “Life is painful and disappointing. It is useless, therefore, to write new realistic novels. We generally know where we stand in relation to reality and don’t care to know any more.”

Although it is tackled in different ways, Houellebecq’s novels all concern how social democratic ideals of personal freedom, equality, and secularism have created a society in the West in which individualism and materialism have become the dominant values. This in turn has led to a deterioration in human relationships and a commodification of sexual desire. He writes in Atomized, “It is interesting to note that the ‘sexual revolution’ was sometimes portrayed as a communal utopia, whereas in fact it was simply another stage in the historical rise of individualism. As the lovely word ‘household’ suggests, the couple and the family would be the last bastion of primitive communism in liberal society. The sexual revolution was to destroy these intermediary communities, the last to separate the individual from the market. The destruction continues to this day.”

Houellebecq proposes that the destruction of the Western system of human values can only be redressed by the creation of a new species that will overcome these issues, albeit at a cost – i.e. losing one’s individuality. This idea is advanced in his novel The Possibility of an Island which promotes cloning of humans as a way of making an individual immortal due to infinite replication. Society then becomes divided into a primitive “human” section that reproduces by sexual means and clones of the original humans. The clones hold all the power while the original humans live like prehistoric bands roaming the Earth and surviving by cannibalism.

In Submission, a book that has been misinterpreted by many critics as being anti-Islam, Houellebecq argues that the more strict moral and societal code of Islam acts to rein in individualism and gives society a value system that provides its followers with meaning and purpose in life. In that sense, he equates Islam with the nationalist French movement and, hence, makes a happy marriage of the two in the novel.

Houellebecq’s writing style violates nearly all the standard rules of good fiction writing, yet it is eminently readable. He unapologetically makes extended asides. To his credit, these asides are often brilliantly written and situate his characters’ struggles in a broader social, historical, and even philosophical context. A master storyteller, Houellebecq can veer from the main story and take his readers along a side path of insightful thoughts, like the Pied Piper.

But he is a Pied Piper with a difference. Not many readers may have the courage to follow him where he takes them, as the journey makes numerous stops in which the characters partake in intense sexual activity, whether by themselves, with a partner, or with multiple partners simultaneously. Sometimes the sexual practices fall towards the more sinister end of the spectrum – realms that are definitely not for the faint hearted. Houellebecq makes no concession to conventional mores.

The repeated and lengthy accounts of orgies in Houellebecque’s novels such as Atomized does beg the question of whether these accounts have literary value. For many of his critics, whether on the Right or on the Left, they do not. More predictably, Houellebecq’s writing also offends the religious establishment, whatever the religion. However, taking offense at these sections of his writing would be a narrow and puritanical way of looking at his work. The descriptions, raw and violent as they may be, are not gratuitous. They are there to serve what the writer is communicating, which is that free sex is a byproduct of individualism in a materialist society. One can also read into the sex-crazed nature of characters like Bruno a reaction to a childhood marked by emotional deprivation. Thus, far from glorifying it, free sex in Houellebecq’s works is seen as a mechanical act that leaves the practitioners feeling empty and depressed.

Somewhat surprisingly, and endearingly, Houellebecq’s protagonists, including the hapless Bruno, do manage to discover what is of value in human relationships – tenderness. In a formative encounter as an adolescent, Bruno realizes “What [he] . had felt was something pure, something gentle, something that predates sex or sensual fulfillment. It was the simple desire to reach out and touch a loving body, to be held in loving arms. Tenderness is a deeper instinct than seduction, which is why it is so difficult to give up hope.”

And if this description of his style indicates that he lacks humour, it would be patently untrue as he can be laugh-aloud funny, even if it is mostly black humour. Some passages in his novel The Possibility of an Island and Whatever are a testimony to this quality of his writing.

Houellebecq’s vision of the future of humankind is the destruction of the human species as we know it and the creation of a new species through advances in genetics and cloning. He writes in Atomized, “[...] humanity must disappear, that humanity would give way to a new species which was asexual and immortal, a species which had outgrown individuality, individuation and progress.”

Aldous Huxley, who finds a number of mentions in Houellebecq’s novels, has a similar vision of human society. In Atomized, Houellebecq writes, “The society Huxley describes in Brave New World is happy; tragedy and extremes of human emotion have disappeared. Sexual liberation is total—nothing stands in the way of instant gratification. Oh, there are little moments of depression, of sadness or doubt, but they’re easily dealt with using advances in anti-depressants and tranquilizers. One cubic centimeter cures ten gloomy sentiments. This is exactly the sort of world we’re trying to create, the world we want to live in.”

And how would a new species of the future see themselves? Houellebecq answers with the following passage in Atomized, somewhat ironically (the “us” in the passage refers to the new species):

“Having broken the filial chain that linked us to humanity, we live on. Men consider us to be happy; it is certainly true that we have succeeded in overcoming the monstrous egotism, cruelty and anger which they could not; we live very different lives. Science and art are still a part of our society, but without the stimulus of personal vanity, the pursuit of Truth and Beauty has taken on a less urgent aspect. To humans of the old species our world seems a paradise. It has even been known for us to refer to ourselves - with a certain humour - by the name which they dreamed of ’gods’.”

It is important to realize that Houellebecq is not offering any cut and dry solutions to the issues facing mankind. The cloning he proposes is, in his own view, is an unsatisfactory solution. However, he is an important writer because he is bold and imaginative, in firstly accepting that the human race is in serious trouble, and secondly presenting a new way of attacking the problem.

To be fully open to the panoply of ideas on offer in Houellebecq’s darkly comic and at times disturbing works requires temporarily suspending one’s preconceived beliefs about moral values and what it means to be a human. Houellebecq tests the reader’s willingness to be receptive and are often goes out of his way to shock. But not being open to new ideas also risks of its own. Resistance to radical ideas is well documented in history. Of course, we have no way of knowing whether the vision of the ideal world of the future, as conceived by visionary writers like Houellebecq and Huxley, is a true utopia or has serious flaws (as shown by the eugenics movement). However, visions of utopias certainly open up a completely new set of possibilities – of an island or more – in the middle of a sea filled with the refuse of reality. And that is what defines great literature.

Houellebecq has produced seven novels to date, the most recent one being Serotonin, published in 2019. All his books have roused controversy but four have taken the literary world by storm and resulted in bouquets and brickbats showered on the writer: The Atomized (also published as The Elementary Particles, 1998), Platform (2001), The Possibility of an Island (2005), and Submission (2015).

Most of Houellebecq’s novels are set in the present, the near future and the distant future. His fiction is infused with elements of science fiction, presenting an alternative vision of human existence. Addressing this, he notes in H.P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life, “Life is painful and disappointing. It is useless, therefore, to write new realistic novels. We generally know where we stand in relation to reality and don’t care to know any more.”

Although it is tackled in different ways, Houellebecq’s novels all concern how social democratic ideals of personal freedom, equality, and secularism have created a society in the West in which individualism and materialism have become the dominant values. This in turn has led to a deterioration in human relationships and a commodification of sexual desire. He writes in Atomized, “It is interesting to note that the ‘sexual revolution’ was sometimes portrayed as a communal utopia, whereas in fact it was simply another stage in the historical rise of individualism. As the lovely word ‘household’ suggests, the couple and the family would be the last bastion of primitive communism in liberal society. The sexual revolution was to destroy these intermediary communities, the last to separate the individual from the market. The destruction continues to this day.”

Houellebecq proposes that the destruction of the Western system of human values can only be redressed by the creation of a new species that will overcome these issues, albeit at a cost – i.e. losing one’s individuality. This idea is advanced in his novel The Possibility of an Island which promotes cloning of humans as a way of making an individual immortal due to infinite replication. Society then becomes divided into a primitive “human” section that reproduces by sexual means and clones of the original humans. The clones hold all the power while the original humans live like prehistoric bands roaming the Earth and surviving by cannibalism.

In Submission, a book that has been misinterpreted by many critics as being anti-Islam, Houellebecq argues that the more strict moral and societal code of Islam acts to rein in individualism and gives society a value system that provides its followers with meaning and purpose in life. In that sense, he equates Islam with the nationalist French movement and, hence, makes a happy marriage of the two in the novel.

Houellebecq’s writing style violates nearly all the standard rules of good fiction writing, yet it is eminently readable. He unapologetically makes extended asides. To his credit, these asides are often brilliantly written and situate his characters’ struggles in a broader social, historical, and even philosophical context. A master storyteller, Houellebecq can veer from the main story and take his readers along a side path of insightful thoughts, like the Pied Piper.

But he is a Pied Piper with a difference. Not many readers may have the courage to follow him where he takes them, as the journey makes numerous stops in which the characters partake in intense sexual activity, whether by themselves, with a partner, or with multiple partners simultaneously. Sometimes the sexual practices fall towards the more sinister end of the spectrum – realms that are definitely not for the faint hearted. Houellebecq makes no concession to conventional mores.

The repeated and lengthy accounts of orgies in Houellebecque’s novels such as Atomized does beg the question of whether these accounts have literary value. For many of his critics, whether on the Right or on the Left, they do not. More predictably, Houellebecq’s writing also offends the religious establishment, whatever the religion. However, taking offense at these sections of his writing would be a narrow and puritanical way of looking at his work. The descriptions, raw and violent as they may be, are not gratuitous. They are there to serve what the writer is communicating, which is that free sex is a byproduct of individualism in a materialist society. One can also read into the sex-crazed nature of characters like Bruno a reaction to a childhood marked by emotional deprivation. Thus, far from glorifying it, free sex in Houellebecq’s works is seen as a mechanical act that leaves the practitioners feeling empty and depressed.

Somewhat surprisingly, and endearingly, Houellebecq’s protagonists, including the hapless Bruno, do manage to discover what is of value in human relationships – tenderness. In a formative encounter as an adolescent, Bruno realizes “What [he] . had felt was something pure, something gentle, something that predates sex or sensual fulfillment. It was the simple desire to reach out and touch a loving body, to be held in loving arms. Tenderness is a deeper instinct than seduction, which is why it is so difficult to give up hope.”

And if this description of his style indicates that he lacks humour, it would be patently untrue as he can be laugh-aloud funny, even if it is mostly black humour. Some passages in his novel The Possibility of an Island and Whatever are a testimony to this quality of his writing.

Houellebecq’s vision of the future of humankind is the destruction of the human species as we know it and the creation of a new species through advances in genetics and cloning. He writes in Atomized, “[...] humanity must disappear, that humanity would give way to a new species which was asexual and immortal, a species which had outgrown individuality, individuation and progress.”

Aldous Huxley, who finds a number of mentions in Houellebecq’s novels, has a similar vision of human society. In Atomized, Houellebecq writes, “The society Huxley describes in Brave New World is happy; tragedy and extremes of human emotion have disappeared. Sexual liberation is total—nothing stands in the way of instant gratification. Oh, there are little moments of depression, of sadness or doubt, but they’re easily dealt with using advances in anti-depressants and tranquilizers. One cubic centimeter cures ten gloomy sentiments. This is exactly the sort of world we’re trying to create, the world we want to live in.”

And how would a new species of the future see themselves? Houellebecq answers with the following passage in Atomized, somewhat ironically (the “us” in the passage refers to the new species):

“Having broken the filial chain that linked us to humanity, we live on. Men consider us to be happy; it is certainly true that we have succeeded in overcoming the monstrous egotism, cruelty and anger which they could not; we live very different lives. Science and art are still a part of our society, but without the stimulus of personal vanity, the pursuit of Truth and Beauty has taken on a less urgent aspect. To humans of the old species our world seems a paradise. It has even been known for us to refer to ourselves - with a certain humour - by the name which they dreamed of ’gods’.”

It is important to realize that Houellebecq is not offering any cut and dry solutions to the issues facing mankind. The cloning he proposes is, in his own view, is an unsatisfactory solution. However, he is an important writer because he is bold and imaginative, in firstly accepting that the human race is in serious trouble, and secondly presenting a new way of attacking the problem.

To be fully open to the panoply of ideas on offer in Houellebecq’s darkly comic and at times disturbing works requires temporarily suspending one’s preconceived beliefs about moral values and what it means to be a human. Houellebecq tests the reader’s willingness to be receptive and are often goes out of his way to shock. But not being open to new ideas also risks of its own. Resistance to radical ideas is well documented in history. Of course, we have no way of knowing whether the vision of the ideal world of the future, as conceived by visionary writers like Houellebecq and Huxley, is a true utopia or has serious flaws (as shown by the eugenics movement). However, visions of utopias certainly open up a completely new set of possibilities – of an island or more – in the middle of a sea filled with the refuse of reality. And that is what defines great literature.