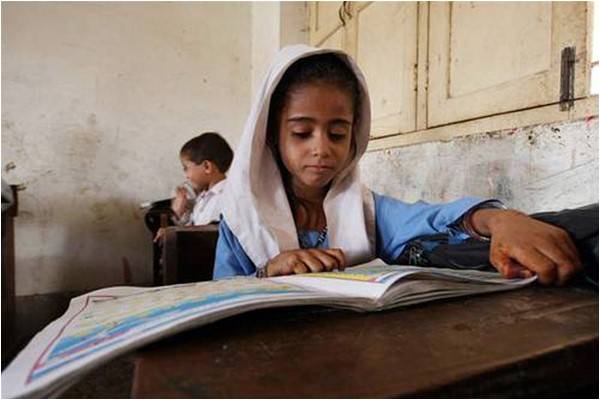

School enrollment has improved over the past six years in Pakistan, but test scores have remained stagnant. Pakistan’s educational system will continue to shortchange kids—especially the poor—until it shifts its focus away from just enrollment, toward improving outcomes. As researchers affiliated with the Center for Economic Research in Pakistan (CERP), we are showing that a simple yet powerful approach using insights from economics to harness market forces may be able to improve school quality, sustainably and affordably.

Researchers around the world have shown that providing information to citizens can improve services for the poor, swiftly and at relatively low cost. That lesson has emerged from large-scale experiments in a variety of countries and sectors. In Uganda, for example, researchers held informational meetings to enable villages to monitor their health centre workers, and this led to better performance and eventually an increase in average child weight and a decrease in child mortality. In India, providing people in informal settlements with information on candidates in the run-up to an election improved turnout, reduced vote buying, and raised the vote share for better-performing and more qualified incumbents.

We wondered if the smart deployment of information could bring about similarly positive effects on education in Pakistan. To find out, we distributed report cards to parents—not the usual report cards that showed the test score of their child alone, but ones that also showed the average scores at all the schools in the village. This was a relatively inexpensive intervention at about Rs100 per child, but it led to dramatic improvements in both private and public schools. Our study, co-authored with World Bank economist Jishnu Das, has just been published in the American Economic Review, one of the leading journals in the field.

A market for education

To fully understand the study and the reasons for its surprising results, first think about markets.

Basic economics tells us that in a well-functioning market you get what you pay for. Sellers charge a higher price for high-quality products and a lower price for low-quality products, and those peddling the worst wares go out of business.

For markets to run smoothly in this way, the buyer must be able to make informed decisions. When you are shopping for mangos at the corner market, you can squeeze and sniff to get most of the information you need and rely on your knowledge of the seller’s reputation for the rest. However, when you are in a market where information about product quality is harder to come by, the market for used cars, for example, you may end up paying the wrong price. “Information asymmetries”, in which sellers know more than buyers, can lead sellers in general (not just the odd swindler) to set prices that fail to communicate the quality of their products to buyers. In such markets the sellers of high-quality goods suffer, in addition to the buyers. In the decades that this phenomenon was first described, economists have experimented with ways to use information to improve markets.

In our study, we looked at schools as sellers of education, and parents as buyers. Local markets for education showed a number of characteristics that could make them both inefficient and difficult to analyse. Information asymmetries were present: parents trying to determine the kind of education on offer were a lot like the average shopper lifting the bonnet, looking at the engine, and trying to guess if the car would break down. Also, the market included both sellers who charged for their product (private schools), and sellers who didn’t, but were subject to more rules and oversight (government schools).

We were able to get around these difficulties in our analysis by treating each village as its own educational market—an approach justified by our finding that that households rarely crossed village boundaries in shopping for schools. This meant that we could conduct our experiment across all participants in the market, rather than just certain buyers and sellers within a larger market (which is how most studies on the effects of information on markets usually work).

Healthy competition

We conducted our experiment in 112 Punjab villages, which had an average of 7.3 schools apiece. That number of choices was driven partly by the rapid growth of low-cost private schools in recent years that we have previously documented in a paper and report. In half of the villages, we created report cards that revealed children’s grades as well as the performance of different private and public schools in the village. We distributed them to both households and schools. We also held meetings to explain scores to parents, as many were illiterate. The other half of villages served as a control group and operated as usual. We gathered baseline surveys and implemented the first round of the experiment during the 2004 school year, then repeated it in 2005.

The results of this experiment were overwhelmingly positive.

First, learning improved. Treatment villages saw average student test scores increase by about 42% of the average yearly gain over student test scores in villages where no information was provided. Remarkably, there were learning gains in government schools too, even though we wouldn’t have expected them to respond to market pressure.

Second, private schools lowered their fees. In treatment villages, fees declined by 17% relative to schools in control villages. Test score gains and price declines were greater among private schools in more competitive villages. This suggests that the report cards enabled parents to comparison-shop, which created pressure on schools to perform better.

Third, enrolment went up. Before the intervention, 76% of boys and 65% of girls aged 5 to 15 were enrolled in school. Overall enrolment among primary-age children rose by 3 percentage points in treatment villages – or about 40 children in each village – apparently a response to the improved educational environment.

Finally, the worst-performing schools went out of business. Private schools with low baseline test scores were more likely to shut down in treatment villages, with their students shifting into alternate schooling options. Also, the test scores of children in initially low-scoring private schools rose. While initially high-scoring schools did not change test scores, they showed larger drops in fees—further evidence of market forces at work.

Our surveys revealed a significant increase in parent-school interactions in treatment villages, but otherwise little change in how much time or money households invested in their children. Instead, the report card intervention seemed to change the way schools responded to increased pressure from parents. We found a modest increase in teacher qualifications in government schools, and an increase in the time spent on schoolwork at initially low-scoring private schools.

It is important to note that we, the researchers, tested the children and constructed the report cards, so we cannot predict what would happen when the government scales up this program, particularly if it is not able to invest in the high-quality systems required to ensure that these measures remain uncorrupted. Still, our experiment shows that schools respond to market forces, and gives grounds for optimism that low-cost interventions can improve learning outcomes in Pakistan.

Supporting schools

Clearly schools, especially low-cost private ones, can play a role not only in giving children quality education, but also driving competition to improve outcomes across all schools. The next step in our research is to test the best ways to support such schools.

While we are working with the public sector as well, low-cost private schooling is a particular area of interest given their proliferation and accessibility. We found such schools have few options if they want to fund improvements and limited access to educational support services. In order to address both these constraints we partnered with Telenor Bank to design and evaluate different financial products that could work for them sustainably, and we have held educational melas that bring village school owners, teachers, and parents face-to-face with representatives from leading educational support services companies. This gives private school owners far better options for classroom materials. The program has also spurred organisations like Oxford University Press to create products appropriate for rural low-cost classrooms, and it has brought school owners, teachers, and parents together on choosing among products and services to improve education quality.

Analysing and removing barriers to schools is just one development of a larger multi-year project that takes a more “system-wide” approach to improve education in Pakistan and is jointly lead by CERP and Evidence for Policy Design (EPoD) at Harvard Kennedy School with support from RISE – a large-scale education systems research program supported by the UK and Australian governments. This work is a continuation of our Learning and Educational Achievements in Pakistan Schools (LEAPS) project started in 2003. In the past LEAPS has looked at the rapid schooling growth in Pakistan and the critical role of locally available, educated women in driving it, and also dispelled myths about the prevalence of madrassas. LEAPS is now expanding this work by better understanding and engaging with all key players in the Pakistani educational ecosystem – from tracking thousands of children’s educational evolution over two decades to working with the public, private and non-profit sectors.

In doing so we hope to bring new but complementary perspectives to the debate. On first glance, viewing knowledge as a commodity may seem callous, however our goal in using economic theory to understand the educational system is to give as many kids as possible the best education the market can offer. Pakistan’s children, especially the poor, are the ones who stand to profit.

Note: Funding for the research cited came from the Templeton Foundation, PEDL, ESRC, World Bank SIEF, and RISE – a large-scale education systems research program supported by the UK and Australian governments. The views expressed are those of the authors alone.

Tahir Andrabi is the Stedman-Sumner Professor of Economics at Pomona College and

Asim Ijaz Khwaja is the Sumitomo-FASID Professor of International Finance & Development and Co-Director of Evidence for Policy Design (EPoD) at Harvard Kennedy School

Researchers around the world have shown that providing information to citizens can improve services for the poor, swiftly and at relatively low cost. That lesson has emerged from large-scale experiments in a variety of countries and sectors. In Uganda, for example, researchers held informational meetings to enable villages to monitor their health centre workers, and this led to better performance and eventually an increase in average child weight and a decrease in child mortality. In India, providing people in informal settlements with information on candidates in the run-up to an election improved turnout, reduced vote buying, and raised the vote share for better-performing and more qualified incumbents.

We wondered if the smart deployment of information could bring about similarly positive effects on education in Pakistan. To find out, we distributed report cards to parents—not the usual report cards that showed the test score of their child alone, but ones that also showed the average scores at all the schools in the village. This was a relatively inexpensive intervention at about Rs100 per child, but it led to dramatic improvements in both private and public schools. Our study, co-authored with World Bank economist Jishnu Das, has just been published in the American Economic Review, one of the leading journals in the field.

We distributed report cards to parents-not the usual report cards that showed the test score of their child alone, but ones that also showed the average scores at all the schools in the village

A market for education

To fully understand the study and the reasons for its surprising results, first think about markets.

Basic economics tells us that in a well-functioning market you get what you pay for. Sellers charge a higher price for high-quality products and a lower price for low-quality products, and those peddling the worst wares go out of business.

For markets to run smoothly in this way, the buyer must be able to make informed decisions. When you are shopping for mangos at the corner market, you can squeeze and sniff to get most of the information you need and rely on your knowledge of the seller’s reputation for the rest. However, when you are in a market where information about product quality is harder to come by, the market for used cars, for example, you may end up paying the wrong price. “Information asymmetries”, in which sellers know more than buyers, can lead sellers in general (not just the odd swindler) to set prices that fail to communicate the quality of their products to buyers. In such markets the sellers of high-quality goods suffer, in addition to the buyers. In the decades that this phenomenon was first described, economists have experimented with ways to use information to improve markets.

In our study, we looked at schools as sellers of education, and parents as buyers. Local markets for education showed a number of characteristics that could make them both inefficient and difficult to analyse. Information asymmetries were present: parents trying to determine the kind of education on offer were a lot like the average shopper lifting the bonnet, looking at the engine, and trying to guess if the car would break down. Also, the market included both sellers who charged for their product (private schools), and sellers who didn’t, but were subject to more rules and oversight (government schools).

We were able to get around these difficulties in our analysis by treating each village as its own educational market—an approach justified by our finding that that households rarely crossed village boundaries in shopping for schools. This meant that we could conduct our experiment across all participants in the market, rather than just certain buyers and sellers within a larger market (which is how most studies on the effects of information on markets usually work).

Healthy competition

We conducted our experiment in 112 Punjab villages, which had an average of 7.3 schools apiece. That number of choices was driven partly by the rapid growth of low-cost private schools in recent years that we have previously documented in a paper and report. In half of the villages, we created report cards that revealed children’s grades as well as the performance of different private and public schools in the village. We distributed them to both households and schools. We also held meetings to explain scores to parents, as many were illiterate. The other half of villages served as a control group and operated as usual. We gathered baseline surveys and implemented the first round of the experiment during the 2004 school year, then repeated it in 2005.

The results of this experiment were overwhelmingly positive.

First, learning improved. Treatment villages saw average student test scores increase by about 42% of the average yearly gain over student test scores in villages where no information was provided. Remarkably, there were learning gains in government schools too, even though we wouldn’t have expected them to respond to market pressure.

Second, private schools lowered their fees. In treatment villages, fees declined by 17% relative to schools in control villages. Test score gains and price declines were greater among private schools in more competitive villages. This suggests that the report cards enabled parents to comparison-shop, which created pressure on schools to perform better.

Third, enrolment went up. Before the intervention, 76% of boys and 65% of girls aged 5 to 15 were enrolled in school. Overall enrolment among primary-age children rose by 3 percentage points in treatment villages – or about 40 children in each village – apparently a response to the improved educational environment.

Finally, the worst-performing schools went out of business. Private schools with low baseline test scores were more likely to shut down in treatment villages, with their students shifting into alternate schooling options. Also, the test scores of children in initially low-scoring private schools rose. While initially high-scoring schools did not change test scores, they showed larger drops in fees—further evidence of market forces at work.

Our surveys revealed a significant increase in parent-school interactions in treatment villages, but otherwise little change in how much time or money households invested in their children. Instead, the report card intervention seemed to change the way schools responded to increased pressure from parents. We found a modest increase in teacher qualifications in government schools, and an increase in the time spent on schoolwork at initially low-scoring private schools.

It is important to note that we, the researchers, tested the children and constructed the report cards, so we cannot predict what would happen when the government scales up this program, particularly if it is not able to invest in the high-quality systems required to ensure that these measures remain uncorrupted. Still, our experiment shows that schools respond to market forces, and gives grounds for optimism that low-cost interventions can improve learning outcomes in Pakistan.

Supporting schools

Clearly schools, especially low-cost private ones, can play a role not only in giving children quality education, but also driving competition to improve outcomes across all schools. The next step in our research is to test the best ways to support such schools.

While we are working with the public sector as well, low-cost private schooling is a particular area of interest given their proliferation and accessibility. We found such schools have few options if they want to fund improvements and limited access to educational support services. In order to address both these constraints we partnered with Telenor Bank to design and evaluate different financial products that could work for them sustainably, and we have held educational melas that bring village school owners, teachers, and parents face-to-face with representatives from leading educational support services companies. This gives private school owners far better options for classroom materials. The program has also spurred organisations like Oxford University Press to create products appropriate for rural low-cost classrooms, and it has brought school owners, teachers, and parents together on choosing among products and services to improve education quality.

Analysing and removing barriers to schools is just one development of a larger multi-year project that takes a more “system-wide” approach to improve education in Pakistan and is jointly lead by CERP and Evidence for Policy Design (EPoD) at Harvard Kennedy School with support from RISE – a large-scale education systems research program supported by the UK and Australian governments. This work is a continuation of our Learning and Educational Achievements in Pakistan Schools (LEAPS) project started in 2003. In the past LEAPS has looked at the rapid schooling growth in Pakistan and the critical role of locally available, educated women in driving it, and also dispelled myths about the prevalence of madrassas. LEAPS is now expanding this work by better understanding and engaging with all key players in the Pakistani educational ecosystem – from tracking thousands of children’s educational evolution over two decades to working with the public, private and non-profit sectors.

In doing so we hope to bring new but complementary perspectives to the debate. On first glance, viewing knowledge as a commodity may seem callous, however our goal in using economic theory to understand the educational system is to give as many kids as possible the best education the market can offer. Pakistan’s children, especially the poor, are the ones who stand to profit.

Note: Funding for the research cited came from the Templeton Foundation, PEDL, ESRC, World Bank SIEF, and RISE – a large-scale education systems research program supported by the UK and Australian governments. The views expressed are those of the authors alone.

Tahir Andrabi is the Stedman-Sumner Professor of Economics at Pomona College and

Asim Ijaz Khwaja is the Sumitomo-FASID Professor of International Finance & Development and Co-Director of Evidence for Policy Design (EPoD) at Harvard Kennedy School