It was like any other morning in Hiroshima on the 6th of August 1945. Children were playing in school yards and mothers were attending to their daily chores at home. Most of the fathers were deployed on battlefields elsewhere.

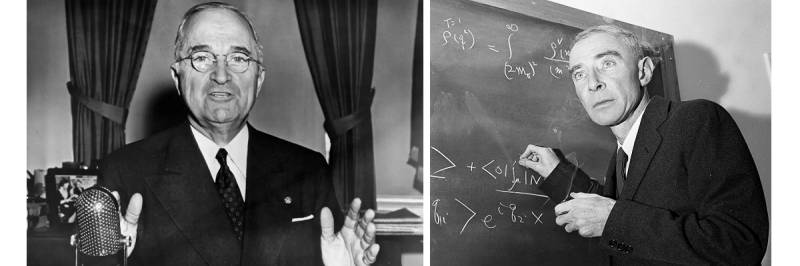

At 08:15, on the orders of President Harry Truman, a single US bomber dropped a single bomb over the centre of the city. In an instant, it wiped out half of the population of 300,000 – mostly women and children. Oppenheimer, the physicist whose life is portrayed in an eponymous biopic, had estimated that some 20,000 would be killed. That was just the number of Korean prisoners of war who the American bomb killed in Hiroshima.

The renowned physicist had spent years working on the science behind the atom bomb. Without his tireless efforts on the Manhattan project in Los Alamos, New Mexico, it would not have been developed in time to bomb Hiroshima. It’s a bitter irony that his crowning achievement would haunt him for the rest of his life. Even the US government disowned him. Albert Einstein captured Oppenheimer’s predicament with a single sentence: “The trouble with Oppenheimer is that he loves a woman who doesn’t love him – the United States government.”

Truman had been in the White House for less than four months before the bomb exploded over Hiroshima. He was President Franklin D Roosevelt’s vice president for four months and assumed the presidency on Roosevelt’s death on 12 April 1945. It was then that he came to know of the Manhattan project on which the US had spent $2 billion.

On 25 July 1945, he wrote in his diary, “We have discovered the most terrible bomb in the history of the world. It may be the fire destruction prophesied in the Euphrates Valley Era, after Noah and his fabulous Ark.” In his biography, Truman, David McCullough says that the president ordered the military to “use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children. Even if the Japs [sic] are savages, ruthless, merciless and fanatic, we as the leader of the world for common welfare cannot drop this bomb on the old capital or the new capital.”

On 31 July, he gave the order to drop the bomb. Truman was returning to the US from the Potsdam Conference with Churchill and Stalin on board the battleship Augusta on 6 August when he got the news that the bomb had dropped over Hiroshima. Addressing a gathering of sailors on the deck of the battleship, a jubilant Truman called the bombing “the greatest thing in history.” For effect, he added: “We have won the gamble.”

Lifton was asked whether President Truman lost any sleep over the decision. He said that even though Truman spent the remaining 25 years of his life defending the decision, he said very different things about it, clearly revealing that he had made no peace with it

He said Japan would not have surrendered without being hit by “the worst weapon in human history.” A land invasion would have cost hundreds of thousands of American and Japanese lives. The atom bomb had saved lives!

On 11 August 2023, National Public Radio, a very respected station in the US, rebroadcast interviews it had conducted with three US experts in 1995, 50 years after bombs were dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Perhaps the most eye-opening interview was that with Robert Jay Lifton, a psychiatrist and widely published author. The interview focused on his book Hiroshima In America. Lifton said the official version that the US “dropped the bomb reluctantly after great reflection only in order to save lives and end the war” is nothing but a myth.

Lifton quoted the press release that the US issued after the bombing. It began with this sentence: “16 hours ago, an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima, an important Japanese army base.” The press release went on to say: “The Japanese began the war from the air at Pearl Harbor. They have been repaid manyfold, and the end is not yet.” Only in the third paragraph did it say that Japan had been hit with an atom bomb which harnesses “the basic power of the universe. The force from which the sun draws its powers has been loosed against those who brought war to the Far East.”

Yes, Japan had an army base in Hiroshima but it was largely a city of 300,000 people. The bomb was dropped over the city centre: it targeted civilians and reduced the city to rubble. Some 90% of the dead were civilians, mostly women and children since the men were at war.

Lifton noted that there was “a very good possibility that Japan would have surrendered if an effort at negotiation was initiated by us or responded to by us with the condition that the emperor be maintained.” The Japanese simply wanted the emperor to retain his symbolic position. They neither had the energy nor the resources to keep on fighting.

The decision to bomb Nagasaki just three days after Hiroshima did not give the Japanese time to process the effects of the first bomb that fell over Hiroshima. It had even less justification than the decision to bomb Hiroshima.

As noted by Arnold Offner in his book, Another Such Victory, “The president’s behaviour lacked remorse, compassion, or humility in the wake of nearly incomprehensible destruction – about 80,000 dead at once and tens of thousands [later estimated at 50-60,000] dying of radiation --- wrought by the ‘most terrible’ weapon in history.” Of the total, perhaps 10,000 were Japanese soldiers.

The reaction in the American press was not positive. The New York Times said we had “sowed the whirlwind.” The Chicago Tribune went further and said that “whole cities may be obliterated in a fraction of a second by a single bomb.” The Kansas City Star said, “We are dealing with an invention that could overwhelm civilisation,” while the St Louis Post-Dispatch warned that science had “signed the mammalian world’s death warrant and deeded the earth in ruins to ants.” The Washington Post warned that the worst imaginary horrors of science fiction had come true.

Yet Truman thought it apt to quote from the Old Testament: “Punishment always follows transgression.” The devout Christian felt he was simply fulfilling God’s will. In his heart of hearts, he felt Japan was a beast, and that “you have to treat a beast like a beast.” Days later, he would contradict himself, saying “because they are beasts, we should not ourselves act in that same manner.”

Offner notes that it was the Soviet Union’s entry into the war on 8 August that persuaded Japan to surrender, not the Nagasaki blast which killed 35,000 at once and thousands more slowly by radiation.

In the 1995 interview, Lifton was asked whether President Truman lost any sleep over the decision. He said that even though Truman spent the remaining 25 years of his life defending the decision, he said very different things about it, clearly revealing that he had made no peace with it. “He sometimes said it was just like an artillery weapon - when you have it, you use it. At other times, he said it was an awesome weapon that should never be used because it kills women and children indiscriminately. He had those dual feelings about the weapon.”

McCullough’s account agrees with this sentiment. He says that even though Truman said many times that once he had made the decision to drop the bomb over Japan, “he went to bed and slept soundly, the opposite was the case. He was sleeping rather poorly and in considerably more turmoil than his later claims suggested.”

Contrary to the official US position, Lifton said that some historians have argued that the bomb probably delayed the end of the war and cost American and Japanese lives rather than having saved them.

On Truman’s death, even Dean Acheson, who was a close associate and later Truman’s secretary of state, questioned whether Truman had made the right decision to drop the atomic bomb over a worn-out and emaciated enemy, killing mostly women and children.

Lifton, now 97 years old, has returned to the topic. In an article published this past month in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, he says that the biopic about the man who brought the atom bomb to life has rekindled the debate over the use of the bomb. He calls it Oppenheimer’s tragedy and ours.

Lefton writes that Oppenheimer’s “greatest tragedy was the success of his leadership in the creation of the weapon.” His remarkable gifts as a physicist and as a human being were most realised in the building of a weapon that could lead to the destruction of humankind.

“In making the bomb, Oppenheimer became immersed in what I call nuclearism—the embrace of the weapon as serving humankind. But with the later development of [the hydrogen bomb, which is] a thousand times more destructive than the Hiroshima bomb, he became an articulate critic of nuclearism, perhaps the most articulate of all critics.”

When the Trinity test was carried out in Los Alamos, Oppenheimer was elated and brimming with excitement as he addressed fellow physicists in Los Alamos.

Lefton continues, “Oppenheimer’s earlier nuclearism included a commitment to the bomb’s use, and that deepened his tragedy. When other scientists involved with its creation engaged in a collective effort to urge that it be given a demonstration in an isolated area rather than exploding it on a human population, Oppenheimer opposed the idea. He did so with some ambivalence, referring to his own ‘anxieties’ about the bomb and partial receptivity to arguments against its use on human beings. But he ended up on the side of those who ‘emphasised the opportunity of saving American lives by immediate military use.’ […] He had become convinced that the military use of the bomb in this war might eliminate all wars.”

Another physicist who worked on the bomb was Philip Morrison. He had an ambiguous attitude toward the use of the bomb until decades later he went to visit Hiroshima and saw what the bomb had done to the city. He noted, “one bomber could now destroy a city.” Lifton notes, “Morrison’s psychological trajectory with the atomic bomb is not too different from Oppenheimer’s.”

Having developed the atom bomb and seen the devastation it unleashed on two Japanese cities, Oppenheimer became sternly opposed to the development of the hydrogen bomb. “He understood that, while an atomic bomb could destroy a city, hydrogen bombs, in tapping the energy of the sun, could destroy the world and eliminate its human inhabitants.”

In October 1945, he went to see Truman privately at the White House. He was already having regrets about having created the bomb. He told the president that he had blood on his hands because of his work on the bomb. McCullough says it was a dreadful moment for Truman. “The blood is on my hands,” he told the physicist who had led the Manhattan Project. Afterward, he said he never wanted to see that “crybaby” again.

A disenchanted man, Oppenheimer spent the rest of his life in vain trying to defuse the nuclear arms race. Lifton, quoting Newsweek, says that today we are all part of Oppenheimer’s tragedy: “Oppenheimer’s life does not [just] influence us. It haunts us.”

By creating the bomb, he empowered Truman to carry out his vendetta against a “savage” enemy, a beast who was “ruthless, merciless and fanatic,” ostensibly to save not only American but also Japanese lives. The tragedy is that millions of Americans swallowed the lie back then and many continue to do so to this day.

It is worth noting that none of the destruction wrought on the people of Hiroshima by the bomb is shown in the Oppenheimer biopic. If it was, very few people would have gone to see it.