Pakistan’s predicament on a water-sharing agreement with India is only getting worse.

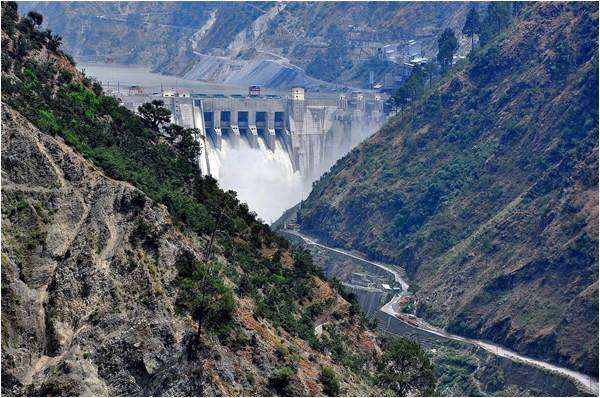

It has been over a week that the World Bank, while conceding to Indian pressure, opted for a time-out on separate requests from Islamabad and Delhi. They have asked for the appointment of a ‘Chairman of the Arbitration Council’ and ‘neutral expert’ for what was described as allowing both parties to consider alternate ways of resolving their dispute over the design of the Kishanganga and Ratle Hydro-power Electric Power projects being constructed by India in Occupied Kashmir. Pakistani officials are still undecided about responding to the World Bank’s move that clearly compromises its interests.

“The relevant ministry is still mulling over the issue,” Foreign Office Spokesman Nafees Zakaria said, reflecting indecisiveness on the Pakistani side. India had, meanwhile, immediately welcomed the move. The Indian position has been that, “It is a matter of satisfaction that our point has now been recognised by the World Bank. We believe that these consultations should be given adequate time.”

The World Bank is expected to send a delegation to both Pakistan and India to nudge them into bilaterally discussing the matter, but chances are bleak that the two will sit down to sort out the issue particularly at a time when they have broken off diplomatic communication. The Indian government, it needs to be recalled, had itself suspended talks with Pakistan on two projects under the Permanent Indus Commission, which provides for the redressal of grievances under the now troubled Indus Water Treaty (IWT).

Although the World Bank explains that the ‘pause’ has been taken to save the IWT from strain, the delay in the initiation of dispute resolution works to India’s advantage as it continues with the two projects. The progress India makes on these projects, experts say, would not be reversible irrespective of the outcome of any future arbitration or mediation depending on whatever course the case takes.

Disputes under the IWT have been a regular feature, more so because the treaty is tilted in India’s favour. Its silence on the number of dams India can build on western rivers (the Indus, Jhelum and Chenab) allocated to Pakistan under the treaty, is just one example. But, the treaty that has withstood wars and crises in the past has lately come under special stress after the militant attack on a military camp in Uri. India has since then been calculatedly upping the pressure on Pakistan by increasingly using water as a weapon of its coercive diplomacy.

Initially, the Indian leadership hinted at revoking the treaty as a ‘punishment’ for Pakistan, but soon modified its position to revisiting the agreement and more recently to making maximum use of waters of the three eastern rivers (Beas, Ravi and Sutlej). A meeting of experts was summoned by the Indian government to explore its options, but it ended with the realization that the choices were limited. IWT’s provisions clearly stipulate that it cannot be unilaterally revoked. Article 12 (4) of IWT states that, “The provisions of this Treaty … shall continue in force until terminated by a duly ratified treaty concluded for that purpose between the two governments.” Thus, there has to be a successor treaty for IWT’s annulment.

Highly water-stressed Pakistan, which greatly depends on the water flowing in from the three western rivers assigned to it under the IWT, would not allow this to happen. “Pakistan will not accept any modifications or changes to the provisions of the Indus Waters Treaty. Our position is based on the principles enshrined in the treaty. And the treaty must be honoured in … letter and spirit,” said Special Assistant to the PM on Foreign Affairs Tariq Fatemi in a media interview.

Therefore, legally India would not be in a position to cancel the treaty. Rhetoric aside, revocation of the IWT would have legal, political and diplomatic implications for India. India itself is a lower riparian country with respect to China, which too can pursue similar measures against it. Nepal, Bangladesh and Myanmar are, meanwhile, also India’s lower riparian countries and such an action would also make them wary of it.

Moreover, technically India is not in a position to block the flows of water in the three western rivers. The options that India can think of, experts say, are unfeasible as they are prohibitively expensive.

Yet India’s willingness to use the IWT blackmail leads to an alarming conclusion: the specter of India ruining Pakistan through a water offensive is back even though the IWT, considered one of the most successful international accords that would guarantee that such an eventuality would not happen.

India may do so by manipulating the river flows to hurt Pakistani agriculture. Its ability to do so may increase when the water storage projects it is undertaking, progress. The Indian government, notwithstanding its evolving position on the IWT, is gradually moving towards the adoption of a tougher strategy on the IWT. Last week Delhi notified a high-powered body to decide strategic steps on the IWT.

The situation poses a serious challenge for Pakistan’s struggling Foreign Office, which would have to raise this issue internationally. “Bring India’s recent threat, statements and actions to the attention of the UN Secretary General (under Article 99 of the UN Charter) and the UNSC,” suggests international law expert Ahmer Bilal Soofi.

The writer is a freelance journalist based in Islamabad and can be reached at mamoonarubab@gmail.com

It has been over a week that the World Bank, while conceding to Indian pressure, opted for a time-out on separate requests from Islamabad and Delhi. They have asked for the appointment of a ‘Chairman of the Arbitration Council’ and ‘neutral expert’ for what was described as allowing both parties to consider alternate ways of resolving their dispute over the design of the Kishanganga and Ratle Hydro-power Electric Power projects being constructed by India in Occupied Kashmir. Pakistani officials are still undecided about responding to the World Bank’s move that clearly compromises its interests.

“The relevant ministry is still mulling over the issue,” Foreign Office Spokesman Nafees Zakaria said, reflecting indecisiveness on the Pakistani side. India had, meanwhile, immediately welcomed the move. The Indian position has been that, “It is a matter of satisfaction that our point has now been recognised by the World Bank. We believe that these consultations should be given adequate time.”

The World Bank is expected to send a delegation to both Pakistan and India to nudge them into bilaterally discussing the matter, but chances are bleak that the two will sit down to sort out the issue particularly at a time when they have broken off diplomatic communication. The Indian government, it needs to be recalled, had itself suspended talks with Pakistan on two projects under the Permanent Indus Commission, which provides for the redressal of grievances under the now troubled Indus Water Treaty (IWT).

Although the World Bank explains that the ‘pause’ has been taken to save the IWT from strain, the delay in the initiation of dispute resolution works to India’s advantage as it continues with the two projects. The progress India makes on these projects, experts say, would not be reversible irrespective of the outcome of any future arbitration or mediation depending on whatever course the case takes.

Disputes under the IWT have been a regular feature, more so because the treaty is tilted in India’s favour. Its silence on the number of dams India can build on western rivers (the Indus, Jhelum and Chenab) allocated to Pakistan under the treaty, is just one example. But, the treaty that has withstood wars and crises in the past has lately come under special stress after the militant attack on a military camp in Uri. India has since then been calculatedly upping the pressure on Pakistan by increasingly using water as a weapon of its coercive diplomacy.

Initially, the Indian leadership hinted at revoking the treaty as a ‘punishment’ for Pakistan, but soon modified its position to revisiting the agreement and more recently to making maximum use of waters of the three eastern rivers (Beas, Ravi and Sutlej). A meeting of experts was summoned by the Indian government to explore its options, but it ended with the realization that the choices were limited. IWT’s provisions clearly stipulate that it cannot be unilaterally revoked. Article 12 (4) of IWT states that, “The provisions of this Treaty … shall continue in force until terminated by a duly ratified treaty concluded for that purpose between the two governments.” Thus, there has to be a successor treaty for IWT’s annulment.

Highly water-stressed Pakistan, which greatly depends on the water flowing in from the three western rivers assigned to it under the IWT, would not allow this to happen. “Pakistan will not accept any modifications or changes to the provisions of the Indus Waters Treaty. Our position is based on the principles enshrined in the treaty. And the treaty must be honoured in … letter and spirit,” said Special Assistant to the PM on Foreign Affairs Tariq Fatemi in a media interview.

Therefore, legally India would not be in a position to cancel the treaty. Rhetoric aside, revocation of the IWT would have legal, political and diplomatic implications for India. India itself is a lower riparian country with respect to China, which too can pursue similar measures against it. Nepal, Bangladesh and Myanmar are, meanwhile, also India’s lower riparian countries and such an action would also make them wary of it.

Moreover, technically India is not in a position to block the flows of water in the three western rivers. The options that India can think of, experts say, are unfeasible as they are prohibitively expensive.

Yet India’s willingness to use the IWT blackmail leads to an alarming conclusion: the specter of India ruining Pakistan through a water offensive is back even though the IWT, considered one of the most successful international accords that would guarantee that such an eventuality would not happen.

India may do so by manipulating the river flows to hurt Pakistani agriculture. Its ability to do so may increase when the water storage projects it is undertaking, progress. The Indian government, notwithstanding its evolving position on the IWT, is gradually moving towards the adoption of a tougher strategy on the IWT. Last week Delhi notified a high-powered body to decide strategic steps on the IWT.

The situation poses a serious challenge for Pakistan’s struggling Foreign Office, which would have to raise this issue internationally. “Bring India’s recent threat, statements and actions to the attention of the UN Secretary General (under Article 99 of the UN Charter) and the UNSC,” suggests international law expert Ahmer Bilal Soofi.

The writer is a freelance journalist based in Islamabad and can be reached at mamoonarubab@gmail.com