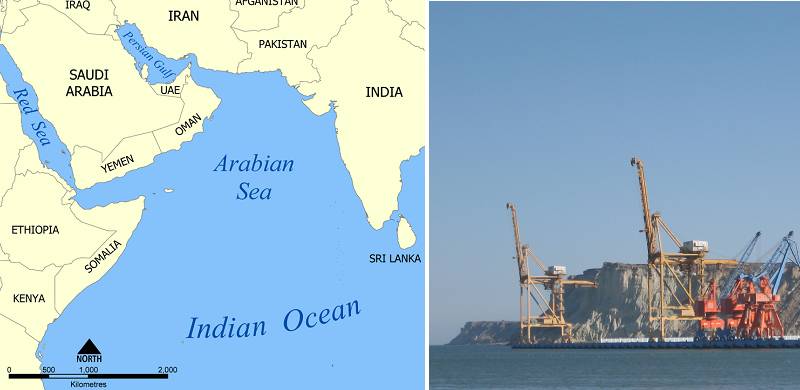

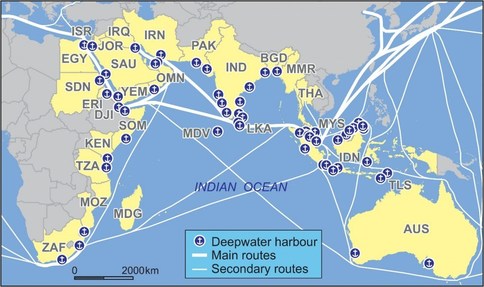

Pakistan has a substantial coastline along the Indian Ocean Rim and from time immemorial what are now its southern provinces have been players in the trade as well as the politics of this most navigated of water bodies. Sadly, since the formation of the modern state of Pakistan, this importance has gradually diminished. Even the international organisations that are in existence with the goal to promote cooperation among the nations along its shores largely ignore Pakistan, at least partly because of India’s unwillingness to allow Pakistan a greater role. An answer to this would be to concentrate on a part of the Indian Ocean that Pakistan can have influence over, and which includes the two most important chokepoints in international sea trade after the Straits of Malacca: namely Hormuz and Bab el Mandab, in the Arabian Sea. All of the oil and gas exiting the Persian/Arabian Gulf through Hormuz has to go through the Arabian Sea – and Bab el Mandab is the entry point into the Red Sea and thus the route to the Suez canal, the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. Pakistan can play a pivotal role in the region by becoming one of the founding members of a proposed regional bloc of nations in and adjacent to the Arabian Sea basin.

The Hindu nationalist government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi has made the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) redundant. Modi’s India refuses to allow SAARC summits to be held if Pakistan is included in any way, and India has thus forsaken SAARC and concentrates on its own brainchild, the Bay of Bengal Initiative – which includes all of the SAARC members except for Pakistan, Afghanistan and the Maldives. The Bay of Bengal Initiative also includes Myanmar and Thailand. India’s prejudice towards Pakistan in international groupings is not a new phenomenon. Long before the rise of Modi, India had openly blocked Pakistan from joining the Indian Ocean Rim Association. Thus, Pakistan has been left out of Indian Ocean cooperation just as it is now being excluded from South Asian cooperation. The answer to this is to form a new regional grouping: one in which India would not, at least initially, be a member – the Arabian Sea Initiative.

This proposed regional grouping would be comprised of Pakistan, Iran, Oman, the United Arab Emirates, the Maldives, Sri Lanka, Yemen, Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia, the Seychelles and Kenya. These countries have Arabian Sea coastlines and control the two vital chokepoints of Hormuz and Bab el Mandab, as well as the busy shipping route south of Sri Lanka which is used by the majority of commercial vessels on their way to Malacca and beyond. The Exclusive Economic Area of these countries covers most of the Arabian Sea itself. A further plus point will be that the only two countries through which Central Asia and western China can directly access the Indian Ocean, Iran and Pakistan, will be important members – and thus the facilitation of Eurasian trade via the Arabian Sea can be achieved through this initiative.

Initially, it would be an entirely trade-based entity, but it can also be a platform for cultural, social and eventually political integration. Some of these nations have particularly close ties with India and that cannot be ignored. Once the Arabian Sea Initiative is launched and begins to function and illustrate its viability, India can be invited to join. Perhaps it may serve as a catalyst for improved bilateral relations between Pakistan and India. But if India does not agree to membership, it can be a strong bulwark against Indian hegemony in the Arabian Sea.

China and Russia can both be observer members in this organisation, especially since China is perhaps the biggest player in the Indian Ocean trade today. Russia, with its vast Eurasian hinterland, can also be brought onboard with facilitating the movement of its goods and services through Central Asia to the Arabian Sea. Thus, Russia’s age old desire to reach the warm tropical waters to the south will finally be realised – but in a peaceful and cooperative way which will ensure co-prosperity for Eurasia.

On the other side of the Indian Ocean, the African member states will receive an economic boost from joining the initiative and the ancient ties that Oman and the Persian Gulf States had with East Africa can be reinvigorated. Africa may just be the next big thing in the global economy: with its vast resources and abundant farmland, the African nations along the Arabian Sea rim can serve as gateway and exit point for larger African trade and investment.

Environmental cooperation can also be an area of focus for the initiative. Because of the vast amounts of pollution being expelled into the Arabian Sea – mostly from South Asia – and the constant pollution due to shipping traffic, there is a vast dead zone in the center of the Arabian Sea. This can be regulated through international cooperation. On the other hand, the Arabian Sea also contains some of the most pristine waters in the world, such as in the Maldives, as well as having biodiversity rich countries such as Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Kenya along its shores. Environmental cooperation can help all of the member states deal with the issue of climate change, which is the single biggest threat to global civilisation.

Environmental cooperation can also be an area of focus for the initiative. Because of the vast amounts of pollution being expelled into the Arabian Sea – mostly from South Asia – and the constant pollution due to shipping traffic, there is a vast dead zone in the center of the Arabian Sea. This can be regulated through international cooperation. On the other hand, the Arabian Sea also contains some of the most pristine waters in the world, such as in the Maldives, as well as having biodiversity rich countries such as Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Kenya along its shores. Environmental cooperation can help all of the member states deal with the issue of climate change, which is the single biggest threat to global civilisation.

The Arabian Sea world has always been a zone of peaceful trade and cooperation. Furthermore, it is this northern part of the Indian Ocean that is vital to global trade, with the vastness of the southern part being navigated far less. The Arabian Sea only became an arena for naval conflict once the Portuguese, French and British arrived on the scene with their ideas of domination rather than cooperation.

It is time that the nations of the Arabian Sea rim unite once more to ensure that the Arabian Sea remains a zone for peaceful trade and cooperation rather than a theatre for global power politics. Pakistan’s potential role in this regard cannot be underestimated, and it can become the unexpected central plank of the region. With the largest population among the member states and having direct land access to China as well as indirect access to Central Asia, it can be the hub for economic activity in the Arabian Sea. Gwadar can be developed to facilitate this, and Karachi is already one of the best situated and busiest ports on the Arabian Sea.

Right now, the Arabian Sea Initiative is just an idea, but if it comes to fruition, it can be one of the globe’s most successful international organisations.

The Hindu nationalist government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi has made the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) redundant. Modi’s India refuses to allow SAARC summits to be held if Pakistan is included in any way, and India has thus forsaken SAARC and concentrates on its own brainchild, the Bay of Bengal Initiative – which includes all of the SAARC members except for Pakistan, Afghanistan and the Maldives. The Bay of Bengal Initiative also includes Myanmar and Thailand. India’s prejudice towards Pakistan in international groupings is not a new phenomenon. Long before the rise of Modi, India had openly blocked Pakistan from joining the Indian Ocean Rim Association. Thus, Pakistan has been left out of Indian Ocean cooperation just as it is now being excluded from South Asian cooperation. The answer to this is to form a new regional grouping: one in which India would not, at least initially, be a member – the Arabian Sea Initiative.

The Arabian Sea only became an arena for naval conflict once the Portuguese, French and British arrived on the scene with their ideas of domination rather than cooperation

This proposed regional grouping would be comprised of Pakistan, Iran, Oman, the United Arab Emirates, the Maldives, Sri Lanka, Yemen, Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia, the Seychelles and Kenya. These countries have Arabian Sea coastlines and control the two vital chokepoints of Hormuz and Bab el Mandab, as well as the busy shipping route south of Sri Lanka which is used by the majority of commercial vessels on their way to Malacca and beyond. The Exclusive Economic Area of these countries covers most of the Arabian Sea itself. A further plus point will be that the only two countries through which Central Asia and western China can directly access the Indian Ocean, Iran and Pakistan, will be important members – and thus the facilitation of Eurasian trade via the Arabian Sea can be achieved through this initiative.

Initially, it would be an entirely trade-based entity, but it can also be a platform for cultural, social and eventually political integration. Some of these nations have particularly close ties with India and that cannot be ignored. Once the Arabian Sea Initiative is launched and begins to function and illustrate its viability, India can be invited to join. Perhaps it may serve as a catalyst for improved bilateral relations between Pakistan and India. But if India does not agree to membership, it can be a strong bulwark against Indian hegemony in the Arabian Sea.

China and Russia can both be observer members in this organisation, especially since China is perhaps the biggest player in the Indian Ocean trade today. Russia, with its vast Eurasian hinterland, can also be brought onboard with facilitating the movement of its goods and services through Central Asia to the Arabian Sea. Thus, Russia’s age old desire to reach the warm tropical waters to the south will finally be realised – but in a peaceful and cooperative way which will ensure co-prosperity for Eurasia.

On the other side of the Indian Ocean, the African member states will receive an economic boost from joining the initiative and the ancient ties that Oman and the Persian Gulf States had with East Africa can be reinvigorated. Africa may just be the next big thing in the global economy: with its vast resources and abundant farmland, the African nations along the Arabian Sea rim can serve as gateway and exit point for larger African trade and investment.

Environmental cooperation can also be an area of focus for the initiative. Because of the vast amounts of pollution being expelled into the Arabian Sea – mostly from South Asia – and the constant pollution due to shipping traffic, there is a vast dead zone in the center of the Arabian Sea. This can be regulated through international cooperation. On the other hand, the Arabian Sea also contains some of the most pristine waters in the world, such as in the Maldives, as well as having biodiversity rich countries such as Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Kenya along its shores. Environmental cooperation can help all of the member states deal with the issue of climate change, which is the single biggest threat to global civilisation.

Environmental cooperation can also be an area of focus for the initiative. Because of the vast amounts of pollution being expelled into the Arabian Sea – mostly from South Asia – and the constant pollution due to shipping traffic, there is a vast dead zone in the center of the Arabian Sea. This can be regulated through international cooperation. On the other hand, the Arabian Sea also contains some of the most pristine waters in the world, such as in the Maldives, as well as having biodiversity rich countries such as Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Kenya along its shores. Environmental cooperation can help all of the member states deal with the issue of climate change, which is the single biggest threat to global civilisation.The Arabian Sea world has always been a zone of peaceful trade and cooperation. Furthermore, it is this northern part of the Indian Ocean that is vital to global trade, with the vastness of the southern part being navigated far less. The Arabian Sea only became an arena for naval conflict once the Portuguese, French and British arrived on the scene with their ideas of domination rather than cooperation.

It is time that the nations of the Arabian Sea rim unite once more to ensure that the Arabian Sea remains a zone for peaceful trade and cooperation rather than a theatre for global power politics. Pakistan’s potential role in this regard cannot be underestimated, and it can become the unexpected central plank of the region. With the largest population among the member states and having direct land access to China as well as indirect access to Central Asia, it can be the hub for economic activity in the Arabian Sea. Gwadar can be developed to facilitate this, and Karachi is already one of the best situated and busiest ports on the Arabian Sea.

Right now, the Arabian Sea Initiative is just an idea, but if it comes to fruition, it can be one of the globe’s most successful international organisations.