I wonder how long it would take a crow to fly from Dibai to Gorakhpur. Though the two qasbas sit on opposite ends of storied Lucknow in the state of Uttar Pradesh, they can’t be that far apart. Yet in many ways what spatial and temporal distances separate the two people germane to the book I review.

Intizar Hussain hailed from Dibai in Bulandshahar district. Growing up in Gorakhpur, Mahmood Farooqui narrates how that meant he could intimately relate with Intizar sahib’s wonderful evocations of idyllic qasba life. That apart, they are men from two altogether different eras and places. Intizar sahib had crossed over to Pakistan long before Mahmood was even born. Thus, like a caravan disappearing in a descending sandstorm the events and places that Intizar Hussain describes in his celebrated novel Basti and other works remain murky imprints only in the memory of those remaining few who witnessed them. A daunting task to therefore capture the essence of a man from another age, and that too a complex and multifarious man like Intizar Hussain. And one also largely inaccessible, living beyond a border that permits crossings whimsically and infrequently. Even the books were not easily accessible and were procured only through the good offices of friends on both sides.

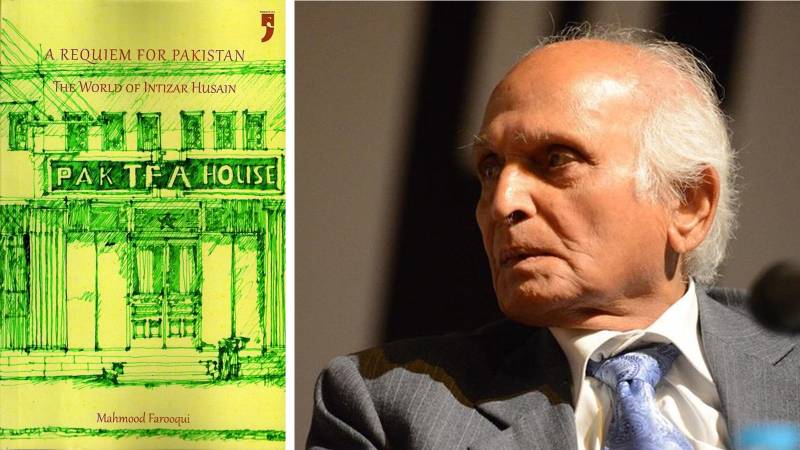

Title: A Requiem for Pakistan: The World of Intizar Hussain

Author: Mahmood Farooqui

Publishers: Yoda Press, New Delhi 2016

In the book, Mahmood engagingly describes the sequence of his literary encounters with the vast and varied world of Intizar Hussain, as he gradually read and discovered more and more of him over the years, adroitly translating multiple passages that particularly moved him. He also records his impressions of their few and far between meetings in person.

Intizar Hussain lived long and deeply, and that too in such tumultuous and conflicting times that any stocktaking of his days is no mean feat. Without a keen sense of history, nuanced appreciation of culture, close reading of literature and understanding of its context, and a resolute will to traverse lines drawn on land and in our imaginations by Partition, reinforced by barbed wires both physical and ideological, such a challenge is insurmountable. Given this, A Requiem of Pakistan: The World of Intizar Hussain is a triumph — a discerning, sensitive and multifaceted study of a remarkable writer and his times that intellectually grapples with and brilliantly captures its political, cultural, and literary discourses and context while remaining highly readable.

Mahmood brings to the table all his rigour and nuance as a gifted historian, his deep knowledge of and passion for the dastan and qissa tradition as the modern reviver and leading exponent of dastangoi, his facility in various languages, and his valuable insights as an actor, director, cultural critic, and litterateur. But even more importantly this book reads like a labor of love. As Iftikhar Arif sahib says about good poetry that you can’t write it if nothing, but whirlpools of dust occupy your heart. I believe that is true for any creative work. Mahmood’s heart is assuredly in this book and thus he seems to have approached all the obstacles spatial and temporal, inspired by Ghalib’s line:

ہم نے دشتِ امکاں کو نقش پا پایا

(Hum Nai Dasht e Imkan ko Naqsh e Pa Paya)

My own imagining and appreciation of Intizar Hussain has always stemmed from three things — his wonderfully poignant nostalgia for his growing years in idyllic small town UP; his resolutely going against the grain exploration and incorporation of Buddhist and Hindu literature and lore and the Persian and Hindustani dastan tradition into Urdu fiction; and his lament for Partition and the resulting alienation that resonates throughout his oeuvre.

Though most of his long adult and creative life was spent in Pakistan the anguish of that parting never really left him. Indeed, he went on to brilliantly explore the themes of separation, persecution, migration, exile, hegemony, alienation, and civilizational loss in all their harrowing avatars and shades in many of his works – with Karbala, 1757, 1857 and 1947 appearing as recurring themes and metaphors. Din and Dastan to my mind are two of his novellas that brilliantly capture all these standard Intizarian themes and preoccupations.

Though the book deeply delves in and discusses all of Intizar Hussain’s characteristic constructs and tropes, it reveals and explores also various additional dimensions of his work — his metaphysical and spiritual explorations; his views on human history; his characterisations of modernism and modern living; his takes on secularism, religion and political projects of Islamisation; his perspective on the purpose and destiny of humankind; his horror at nuclear proliferation; his aversion to anthropocentricism and his love for birds, trees and bio-diversity, and much more.

What is fascinating also is how he managed to reconcile, synergise and benefit from such diverse literary influences as western literature, the Hindu and Buddhist literary traditions and the Persian and Arabic literary heritage. Engaging both with tales from the grandmother’s stove and the western existentialist movement, Intizar Hussain nevertheless always maintained his own special stance and place even as the winds of various literary movements raged around him.

The chapters in the book woven around the Progressive Movement, the literary circles of Lahore and its publishing environment, and cultural icons and close friends of Intizar Hussain, such as the maverick critic Muhammad Hasan Askari, the poet of unmatched pathos Nasir Kazmi, the gifted playwright Reoti Saran Sharma, and indeed many other luminaries of the time, are particularly insightful.

Through this extensive work we witness Intizar Hussain in his varied roles as a writer, pacifist, columnist, literary critic, environmentalist, and citizen. Arguably his most significant facet and contribution — and one which this book highlights with great success — is his exploration, questioning and deconstruction of the notion of identity. More specifically, identity as artificially constructed by modern nation states while they deface identity formulation brought about by centuries of cultural evolution, societal interface and lived human experience.

Whether as a spokesperson of the pluralist Ganga Jamni Tehzeeb or as someone dissecting the phenomenon of Indo-Muslim identity, Intizar Hussain has been one of the central literary figures in these discourses on identity. Much more amorphous are his perspectives on whether there is any divine mission for humanity; however, there is a lot at the more mundane level, he appears to say, that needs to be done to make humans more humane. For it is the brutality of human history that bothers him much more than the enigma of human existence.

Throughout the book Mahmood undertakes nuanced and close textual analysis of Intizar Hussain’s works to help us understand more intimately the value of these texts and their continued relevance today. Live as he did through for decades in a country besieged by military authoritarianism, religious radicalisation and terrorism, it is not hard to predict what Intizar Hussain would have thought of the woeful and rapid slide by India towards religious obscurantism, intolerance and persecution, and thereby the undesirable justification for a requiem of its own.

One is persuaded that it would have only deepened his convictions as to the necessity for human bonds to transcend divides and for people to coalesce to resist hegemonies, occupations and forced alienations. Not just an informed and engaging biography this is where Mahmood elevates the text to make it an important critical engagement with multiple ideas and ideologies that continue to impact us as peoples, as a race, and as a species.

One striking example of how the hegemony of barbed wires keeps people on either side unable to interact and mutually flourish is the ban on trade of various good, including most ignominiously books. A travesty which in its dire consequences is no different from that we find in Philip K Dick’s iconic work Fahrenheit 451. For whether burnt or banned, the end result is that books aren’t accessible. The very hegemony that Intizar Hussain bemoans is what keeps a book about this great Pakistani writer by a brilliant Indian writer and a text that is highly relevant and of interest to people on both sides, unavailable in Pakistan. High time this self-defeating ban ends, the book routinely breezes through the gates at Wagah, and is also published in Pakistan.