On February 15, the Pakistan Army formally declared its intention to deploy troops in Saudi Arabia under a bilateral security pact with the proviso that the Pakistani contingent will not be ‘employed outside KSA’.

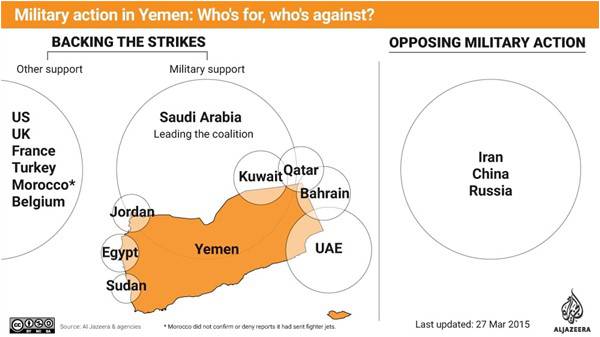

This announcement ended speculation about covert military cooperation between Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, generated particularly after the Pakistani parliament demurred to send troops to fight in the Saudi-armed intervention in Yemen.

The ISPR has rightly emphasised the long history of security cooperation between Pakistan and several Arab countries dating to the 1970s and 80s when many Arab countries sought Pakistani military support, owing to the rather tentative combat and non-combat skills of their armed forces. Resultantly, contingents of Pakistan army and air force were stationed at Bahrain, Qatar, Jordan and Saudi Arabia. Pakistani detachments, rotated regularly, were smaller in number and were mostly engaged in training local forces and manning complicated equipment such as missile sites and radar stations.

Initially their presence was frowned upon by rival progressive power dispensations in Egypt, Syria and Iraq as it was thought to be propping up the anachronistic monarchical regimes in Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Bahrain and the UAE. The situation was aggravated when a Pakistani contingent in Jordan, under command of Pakistani brigadier (later general) Zia-ul Haq, cracked down on the Palestinian armed resistance against the regime of King Hussein. As a matter of fact, the presence of Pakistani troops in Saudi Arabia during the Iran-Iraq War aroused considerable ire in official circles of Iran and may have been instrumental in causing a decisive Iranian tilt towards India at a later stage.

The spill-over of a lengthened Iran-Iraq war (1980-88) created a scare in the region, compelling Saudi Arabia to seek an enlarged Pakistani security presence on its soil substantiated by a formal and well-knit agreement. The Saudi leadership took some time to overcome its internal bickering about the regular stationing of large Pakistani ground troops (some two-division strong) as they thought it to run contrary to their plans of increasing their twin security outfits—regular army and Saudi Arabian National Guards (SANG)—and finally agreed to receive a watered-down brigade strength detachment.

After signing an agreement in 1982, both countries established the Saudi Pakistan Armed Forces Organization (SPAFO) that stationed Pakistani troops at Tabuk and Khamis Mushayt. The self-contained Pakistani formations were commanded by a brigadier and their last commander was Brigadier Jahangir Karamat (later COAS) from 1985 to 1988. After the end of the Iran-Iraq war the need for Pakistani troops lessened as by that time Saudi land forces were enlarged, modernized and trained by America and Britain.

At the advent of the First Gulf War, western forces were deployed in Saudi Arabia, eliciting a furious response from its citizenry that closed the door for such deployment in future. Though the deployment of western troops reduced the need for Pakistani armed presence in Saudi Arabia, mutual security cooperation turned towards the provision of the Pakistani nuclear umbrella to ward off any Iranian aggression. Despite strong conjecturing in western countries about a rumoured deal between Pakistan and Saudi Arabia about supplying a nuclear device, no proof of such an occurrence has ever emerged. There was, however, a close intelligence relationship that invariably focused on curbing activities of extremist groups operating in the region and their covert efforts were rarely made public.

Along with indigenous insecurities, the theocratic persuasion of the Kingdom considers Shia influence in the region a counter force out to harm it. It considers itself to be ringed by the growing influence of Iran in the region, particularly its effective involvement in Syria, Iraq and Lebanon. It is also concerned about a Shia government in Iraq, sporadic unrest in Shia-majority Bahrain and the menacingly independent stance of Qatar.

In the wake of its inability to deploy western troops on its soil, the Kingdom is not happy to see Qatar housing a sizeable presence of US troops in the shape of the Combined Air and Space Operations Centre (CAOC) whose 11,000 troops are placed to oversee US military air power in Afghanistan, Syria Iraq and 18 other countries, with the capacity to accommodate 120 aircraft.

Furthermore, the presence of a small but lethal extremist element within the Kingdom has caused tremendous anxiety for Saudi policy makers. The non-state actors periodically hit targets although Saudis effectively retaliate against them. The worry is exacerbated by persistent unrest in Shia-dominated regions that are a source of oil production in the Kingdom. In 2016, the Saudi leadership executed a Shia cleric Nimr Baqir al-Nimr operating in the town of al-Awamiyah of its Eastern province who was popular among youth and frequently criticised the Saudi government.

The situation grew complicated after the demise of King Abdullah in 2015 as the internal power shift in the Kingdom saw the rise of the Sudairi faction of the royal family that brought an upsurge in security cooperation with Pakistan. The rift in the royal family underscored the unreliability of the alternate source of security outfit—SANG—mostly manned by tribal personnel loyal to the late King Abdullah, whose commander Prince Miteb bin Abdullah was not only removed from its command but also arrested in the ‘anti-corruption’ drive of the crown prince and de-facto ruler Prince Muhammad bin Salman.

Till then the Saudi internal security doctrine was carefully woven to balance regular army and SANG to prevent an armed coup against the ruling house. The doctrine aimed at discouraging unity between the regular army and SANG with both of them keeping a check on each other. SANG was also divided into regular reserve stationed into probable flash-points. But the difficulty that ensued for the Sudairi faction after acquiring power was that it distrusted both SANG and the regular army, giving rise to the need for an interim third force till the power-holders gained complete loyalty of the armed cadres.

The palpably potential threat to its power base constrained the Saudi regime to look towards Pakistan for security succour. In the annals of monarchical ruling practices, it is not considered improper to use foreign forces to protect a hold on power and the advantage with the Pakistanis is that they have experience of scouting and navigating foreign power tussles.

The consistent efforts of the Saudi leadership to woo the Pakistani military’s help is due to the instability of the current Saudi power paradigm as was evident during the widespread arrest of influential Saudi princes in November 2017, that included, unconventionally, laying hands on the sons of late kings Abdullah (Miteb and Turki) and Fahd (Abdul Aziz who was initially and wrongly reported dead in an armed skirmish with forces coming to arrest him). The dilemma Saudi leadership faces pertains to the willingness of indigenous security personnel to coercively confront their countrymen.

To give their requirement for ground troops a palatable ring the Saudis elevated General Raheel Sharif as the supremo of the Islamic Military Alliance. He was mandated to negotiate troop deployment with his Pakistani counterpart (the current COAS) who had served under him. Raheel Sharif is an ideal man to gather a bevy of select senior officers such as retired lieutenant-generals Ashfaq Nadeem Ahmad and Rizwan Akhtar on the regular strength of the IMA and many serving army officers, particularly from his parent FF regiment, to serve with him in the IMA on secondment. It may, however, be conceded that stationing Pakistani troops in Saudi Arabia will not only increase the influence of the Pakistani security establishment there but will also prove to be a long-term advantage for Pakistan.

Ali Siddiqi is a former bureaucrat and runs an academic training outfit in Karachi. He can be reached at tviuk@hotmail.com

This announcement ended speculation about covert military cooperation between Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, generated particularly after the Pakistani parliament demurred to send troops to fight in the Saudi-armed intervention in Yemen.

The ISPR has rightly emphasised the long history of security cooperation between Pakistan and several Arab countries dating to the 1970s and 80s when many Arab countries sought Pakistani military support, owing to the rather tentative combat and non-combat skills of their armed forces. Resultantly, contingents of Pakistan army and air force were stationed at Bahrain, Qatar, Jordan and Saudi Arabia. Pakistani detachments, rotated regularly, were smaller in number and were mostly engaged in training local forces and manning complicated equipment such as missile sites and radar stations.

Initially their presence was frowned upon by rival progressive power dispensations in Egypt, Syria and Iraq as it was thought to be propping up the anachronistic monarchical regimes in Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Bahrain and the UAE. The situation was aggravated when a Pakistani contingent in Jordan, under command of Pakistani brigadier (later general) Zia-ul Haq, cracked down on the Palestinian armed resistance against the regime of King Hussein. As a matter of fact, the presence of Pakistani troops in Saudi Arabia during the Iran-Iraq War aroused considerable ire in official circles of Iran and may have been instrumental in causing a decisive Iranian tilt towards India at a later stage.

The spill-over of a lengthened Iran-Iraq war (1980-88) created a scare in the region, compelling Saudi Arabia to seek an enlarged Pakistani security presence on its soil substantiated by a formal and well-knit agreement. The Saudi leadership took some time to overcome its internal bickering about the regular stationing of large Pakistani ground troops (some two-division strong) as they thought it to run contrary to their plans of increasing their twin security outfits—regular army and Saudi Arabian National Guards (SANG)—and finally agreed to receive a watered-down brigade strength detachment.

After signing an agreement in 1982, both countries established the Saudi Pakistan Armed Forces Organization (SPAFO) that stationed Pakistani troops at Tabuk and Khamis Mushayt. The self-contained Pakistani formations were commanded by a brigadier and their last commander was Brigadier Jahangir Karamat (later COAS) from 1985 to 1988. After the end of the Iran-Iraq war the need for Pakistani troops lessened as by that time Saudi land forces were enlarged, modernized and trained by America and Britain.

At the advent of the First Gulf War, western forces were deployed in Saudi Arabia, eliciting a furious response from its citizenry that closed the door for such deployment in future. Though the deployment of western troops reduced the need for Pakistani armed presence in Saudi Arabia, mutual security cooperation turned towards the provision of the Pakistani nuclear umbrella to ward off any Iranian aggression. Despite strong conjecturing in western countries about a rumoured deal between Pakistan and Saudi Arabia about supplying a nuclear device, no proof of such an occurrence has ever emerged. There was, however, a close intelligence relationship that invariably focused on curbing activities of extremist groups operating in the region and their covert efforts were rarely made public.

Along with indigenous insecurities, the theocratic persuasion of the Kingdom considers Shia influence in the region a counter force out to harm it. It considers itself to be ringed by the growing influence of Iran in the region, particularly its effective involvement in Syria, Iraq and Lebanon. It is also concerned about a Shia government in Iraq, sporadic unrest in Shia-majority Bahrain and the menacingly independent stance of Qatar.

The presence of Pakistani troops in Saudi Arabia during the Iran-Iraq War aroused considerable ire in official circles of Iran and may have been instrumental in causing a decisive Iranian tilt towards India at a later stage

In the wake of its inability to deploy western troops on its soil, the Kingdom is not happy to see Qatar housing a sizeable presence of US troops in the shape of the Combined Air and Space Operations Centre (CAOC) whose 11,000 troops are placed to oversee US military air power in Afghanistan, Syria Iraq and 18 other countries, with the capacity to accommodate 120 aircraft.

Furthermore, the presence of a small but lethal extremist element within the Kingdom has caused tremendous anxiety for Saudi policy makers. The non-state actors periodically hit targets although Saudis effectively retaliate against them. The worry is exacerbated by persistent unrest in Shia-dominated regions that are a source of oil production in the Kingdom. In 2016, the Saudi leadership executed a Shia cleric Nimr Baqir al-Nimr operating in the town of al-Awamiyah of its Eastern province who was popular among youth and frequently criticised the Saudi government.

The situation grew complicated after the demise of King Abdullah in 2015 as the internal power shift in the Kingdom saw the rise of the Sudairi faction of the royal family that brought an upsurge in security cooperation with Pakistan. The rift in the royal family underscored the unreliability of the alternate source of security outfit—SANG—mostly manned by tribal personnel loyal to the late King Abdullah, whose commander Prince Miteb bin Abdullah was not only removed from its command but also arrested in the ‘anti-corruption’ drive of the crown prince and de-facto ruler Prince Muhammad bin Salman.

Till then the Saudi internal security doctrine was carefully woven to balance regular army and SANG to prevent an armed coup against the ruling house. The doctrine aimed at discouraging unity between the regular army and SANG with both of them keeping a check on each other. SANG was also divided into regular reserve stationed into probable flash-points. But the difficulty that ensued for the Sudairi faction after acquiring power was that it distrusted both SANG and the regular army, giving rise to the need for an interim third force till the power-holders gained complete loyalty of the armed cadres.

The palpably potential threat to its power base constrained the Saudi regime to look towards Pakistan for security succour. In the annals of monarchical ruling practices, it is not considered improper to use foreign forces to protect a hold on power and the advantage with the Pakistanis is that they have experience of scouting and navigating foreign power tussles.

The consistent efforts of the Saudi leadership to woo the Pakistani military’s help is due to the instability of the current Saudi power paradigm as was evident during the widespread arrest of influential Saudi princes in November 2017, that included, unconventionally, laying hands on the sons of late kings Abdullah (Miteb and Turki) and Fahd (Abdul Aziz who was initially and wrongly reported dead in an armed skirmish with forces coming to arrest him). The dilemma Saudi leadership faces pertains to the willingness of indigenous security personnel to coercively confront their countrymen.

To give their requirement for ground troops a palatable ring the Saudis elevated General Raheel Sharif as the supremo of the Islamic Military Alliance. He was mandated to negotiate troop deployment with his Pakistani counterpart (the current COAS) who had served under him. Raheel Sharif is an ideal man to gather a bevy of select senior officers such as retired lieutenant-generals Ashfaq Nadeem Ahmad and Rizwan Akhtar on the regular strength of the IMA and many serving army officers, particularly from his parent FF regiment, to serve with him in the IMA on secondment. It may, however, be conceded that stationing Pakistani troops in Saudi Arabia will not only increase the influence of the Pakistani security establishment there but will also prove to be a long-term advantage for Pakistan.

Ali Siddiqi is a former bureaucrat and runs an academic training outfit in Karachi. He can be reached at tviuk@hotmail.com