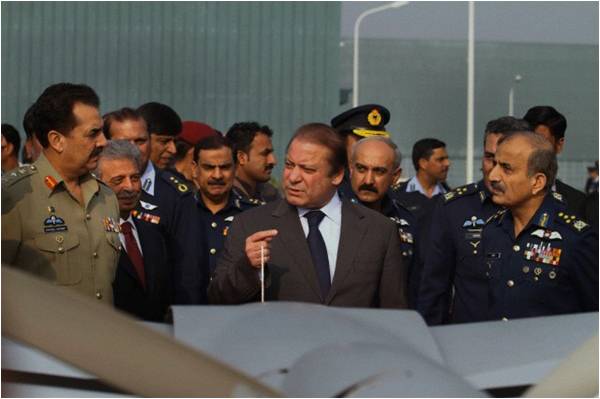

Amid the crippling petrol, gas and power crisis, the dithering civilians are thumping their chests to be the real representatives of the suffering people, with little long-term relief for the latter in sight. The omnipresent military establishment is quietly reaching out to all those who matter for Pakistan’s strategic interests. Nawaz Sharif, along with his family and friends, is praying for the Saudi King’s health at Mecca. Gen Raheel Sharif, on the other hand, is peddling hard abroad. While the Ministry of Foreign Affairs keeps adjusting itself to the winks and whims of a resigned prime minister, the GHQ is on a full-throttle diplomatic offensive to engage Americans, the Brits and Afghans like never before. The delineation of power is clear.

The Foreign Ministry seems to be held back by its laid back seniors. Even those who would want to upend the GHQ keep cringing helplessly because of their two cautious bosses. The relatively younger, more dynamic senior military leadership, on the other hand, is lunging for opportunities to network wherever possible. Besides General Sharif, the ISI chief, and those leading the southern and northern commands, are busy repairing relations with the US and the Afghans. Look at the string of military visits to Kabul, starting with the December 17 air-dash f Gen Sharif to Kabul, followed by the ISI chief, and the Peshawar corps commander.

Where is the civilian command in the entire Afghanistan-Pakistan matrix? Busy in petty political rhetoric (trying to outgun Imran Khan) or personal enrichment pursuits. The record hardly speaks for them. On January 6, they surrendered even the judicial powers to the army and that too with a thumping near-unanimity. And then half of the country sank in the oil crisis for well over a week, forcing citizens to queue up for diesel and petrol. What next? Will the Petroleum Ministry be handed over to the GHQ, or the Civil Aviation Authority (so it can complete the new Islamabad airport) or the long-overdue Criminal Procedure Code reforms (which sits at the heart of Pakistan’s tardy legal justice system and obstructs speedy justice)? Or will the army also be asked to help in police reforms (which they apparently don’t want)? Or the champions of democracy could possibly request the GHQ to help in devolution of power via local government elections (which most mainstream politicians abhor)?

A much more daunting challenge will be neutralizing and dismantling the non-state actors. Civilians rightly blame their existence and their penetration of the society on the GHQ, but will they now take the bull by the horn? Much depends on how and whether the civilian government deploys police – globally acknowledged as the major tool to fight insurgencies and non-state actors.

Nawaz Sharif may want good relations with both India and Afghanistan but he cannot shirk the fact that Jamaatud Dawa (or Lashkar-e-Taiba) remains the sore point in the country’s adversarial relationship with India. Similarly, governmental claims about the Haqqani Network and members of the Hezb-e-Islami notwithstanding, movements to and from Pakistan of key members of these groups continue to represent an eyesore for the Afghan authorities.

That is why, even though President Barack Obama reiterated the US support for Pakistan in his State of the Union address on January 20, and vowed to pursue terrorists from Peshawar to Paris, this expression of support is not likely to change his administration’s view on the Haqqani Network and the LeT. New Delhi and Kabul provide the basic ingredients for the American narrative on Islamabad’s thus far “murky and duplicitous” position on the two militant outfits.

And this represents a huge challenge for both the Sharifs. As Pakistanis discern certain ‘paradigm shifts’, they once again are faced with a dichotomous, unnerving situation, which can potentially erode the newborn optimism quite easily. The context is the string of stories attributed to officials that the government has decided to ban the Haqqani Network and the JuD. But on January 17, Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan evaded a question on the Haqqani Network, promising the questioner a private audience. This ambiguity raises serious questions about the government’s intent. One may — theoretically, at least — accept the government’s possible defence that the Haqqani Network is an Afghan entity operating in Afghan territory. But it cannot duck under the same excuse as far as the LeT/ or JuD is concerned. Only a meaningful proscription and credible administrative actions against the two would help retain public confidence because most Pakistanis — both inside and outside the country — remain extremely skeptical of all official claims.

Will the civilian Sharif upend General Sharif by exercising his parliamentary authority and do what the world including US and India expect of him? Or will he leave this demanding task to the military too, and thus bring the latter in direct confrontation with its former allies? This could potentially trigger a civil war in Sharif’s home Punjab – the headquarters for many banned entities, including the LeT. If civilians wish Pakistan to survive, they will have to take charge of key affairs rather than outsourcing them to the GHQ, hoping that would eventually bog down the military establishment. The cost for that would certainly be enormous. The best way to upstage the military and cut it out of political economy is integrity, vision, courage and regard for rule of law and merit.

The Foreign Ministry seems to be held back by its laid back seniors. Even those who would want to upend the GHQ keep cringing helplessly because of their two cautious bosses. The relatively younger, more dynamic senior military leadership, on the other hand, is lunging for opportunities to network wherever possible. Besides General Sharif, the ISI chief, and those leading the southern and northern commands, are busy repairing relations with the US and the Afghans. Look at the string of military visits to Kabul, starting with the December 17 air-dash f Gen Sharif to Kabul, followed by the ISI chief, and the Peshawar corps commander.

Where is the civilian command in the entire Afghanistan-Pakistan matrix? Busy in petty political rhetoric (trying to outgun Imran Khan) or personal enrichment pursuits. The record hardly speaks for them. On January 6, they surrendered even the judicial powers to the army and that too with a thumping near-unanimity. And then half of the country sank in the oil crisis for well over a week, forcing citizens to queue up for diesel and petrol. What next? Will the Petroleum Ministry be handed over to the GHQ, or the Civil Aviation Authority (so it can complete the new Islamabad airport) or the long-overdue Criminal Procedure Code reforms (which sits at the heart of Pakistan’s tardy legal justice system and obstructs speedy justice)? Or will the army also be asked to help in police reforms (which they apparently don’t want)? Or the champions of democracy could possibly request the GHQ to help in devolution of power via local government elections (which most mainstream politicians abhor)?

A much more daunting challenge will be neutralizing and dismantling the non-state actors. Civilians rightly blame their existence and their penetration of the society on the GHQ, but will they now take the bull by the horn? Much depends on how and whether the civilian government deploys police – globally acknowledged as the major tool to fight insurgencies and non-state actors.

Will the Petroleum Ministry be handed over to the GHQ?

Nawaz Sharif may want good relations with both India and Afghanistan but he cannot shirk the fact that Jamaatud Dawa (or Lashkar-e-Taiba) remains the sore point in the country’s adversarial relationship with India. Similarly, governmental claims about the Haqqani Network and members of the Hezb-e-Islami notwithstanding, movements to and from Pakistan of key members of these groups continue to represent an eyesore for the Afghan authorities.

That is why, even though President Barack Obama reiterated the US support for Pakistan in his State of the Union address on January 20, and vowed to pursue terrorists from Peshawar to Paris, this expression of support is not likely to change his administration’s view on the Haqqani Network and the LeT. New Delhi and Kabul provide the basic ingredients for the American narrative on Islamabad’s thus far “murky and duplicitous” position on the two militant outfits.

And this represents a huge challenge for both the Sharifs. As Pakistanis discern certain ‘paradigm shifts’, they once again are faced with a dichotomous, unnerving situation, which can potentially erode the newborn optimism quite easily. The context is the string of stories attributed to officials that the government has decided to ban the Haqqani Network and the JuD. But on January 17, Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan evaded a question on the Haqqani Network, promising the questioner a private audience. This ambiguity raises serious questions about the government’s intent. One may — theoretically, at least — accept the government’s possible defence that the Haqqani Network is an Afghan entity operating in Afghan territory. But it cannot duck under the same excuse as far as the LeT/ or JuD is concerned. Only a meaningful proscription and credible administrative actions against the two would help retain public confidence because most Pakistanis — both inside and outside the country — remain extremely skeptical of all official claims.

Will the civilian Sharif upend General Sharif by exercising his parliamentary authority and do what the world including US and India expect of him? Or will he leave this demanding task to the military too, and thus bring the latter in direct confrontation with its former allies? This could potentially trigger a civil war in Sharif’s home Punjab – the headquarters for many banned entities, including the LeT. If civilians wish Pakistan to survive, they will have to take charge of key affairs rather than outsourcing them to the GHQ, hoping that would eventually bog down the military establishment. The cost for that would certainly be enormous. The best way to upstage the military and cut it out of political economy is integrity, vision, courage and regard for rule of law and merit.