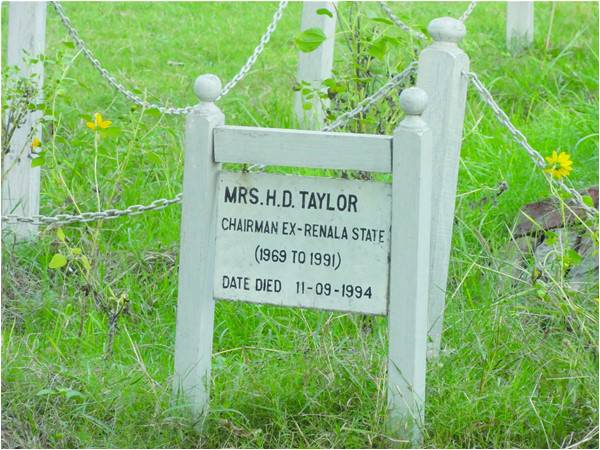

The shoes, though buried under piles of dust but neatly tucked away in the cupboards, said something about their owner. So did the sofas and chairs that were sitting in the living room. The piano looked as if it was just waiting for someone to play it, and the grandfather clock’s hands had stopped at almost nine o’ clock. It must have stopped on September 11, 1994, the day that Mrs H. D. Taylor of Renala Estate Ltd died.

There were signs that people had rummaged through her property but it still smelt of her. Walking around her ample bungalow, I wondered who she had been. Why did she not move away when the time was right? Why did she choose to be buried thousands of miles away from home, in a land where she was humiliated and even physically harassed during her last days?

It was sheer accident that I came upon Mrs. Hazel Deneys Taylor’s grave outside her farmhouse in Renala Khurd. I was searching for signs of radicalism in Punjab and did not expect to find the last abode of a white British woman in the hometown of Zakiurehman Lakhvi, the Lashkar-e Tayyaba, Jammat-ud-Dawa bigwig. Indeed, when Lakhvi went to fight his first battle in Afghanistan on the side of the first generation of Afghan warlords, Mrs. Taylor was still alive and in control of her farm. She seems to have lived peacefully with the people in an area which is one of the hubs of ahl-e Hadith in central Punjab. But then, the organic ahl-e Hadith of the area was not violent. In fact, the Lakhvis are a big clan and some of the notables contest elections and act as local pirs, despite being ahl-e Hadith. Could it be that they did not want to hurt an elderly woman who had spent almost her entire life in that area?

When the British established the irrigation system in Punjab and introduced the Colonization of Land Act 1912, one of the first leases in the region was given to one Major Deneys Henry Vanrenen in 1915. This is probably where Hazel had come to live with her parents. Compromising villages 20/1RB, 21/1RB, 22/1RB, 23/1RB, 13A/1R, and 14A/1R, the lease was from 1915 to 1935. The 20-year lease was later extended for another 10 years until 1945. However, Major Vanrenen died in 1938 and his daughter Hazel, along with her husband Col. John F. L. Taylor, managed the lease. It appears from records of the chartered accountant firm A. F. Ferguson & Co. that both husband and wife held shares in Renala Estate Limited.

Unmindful of the local political conditions, the couple developed the farmland, and facilitated the building of roads, the Renala railway station, a police station, and stables for horses, a paddock, and a model village. Impressed by their performance, the colonial state extended the lease for another ten years with the promise that the Taylors would be able to buy the farm at the end of the ten-year period.

But things changed soon after. The farm took a hit due to the torrential rainfall in 1948 when 4,500 out of 7,723 acres became waterlogged. But this was just the beginning of problems for the Taylors, especially after the lease expired in 1955 when other stakeholders in the area challenged the ownership. However, the then deputy commissioner of Multan, under whose control the land fell, Sardar Atta Mohammad Laghari, decided in favor of the Taylors and offered them an extension of the lease for another 10 years.

Eventually, the lease was extended from 1969 to 1979, a year after Col. John Taylor’s death in 1968. This extension did not ease pressure from Mrs. Taylor as soon after, in 1971, President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto ordered the confiscation of the land under martial law regulation 115. But the then Federal Land Commission that was moved in this case gave its judgment that regulation 115 did not apply on this land. Consequently, Mrs. Taylor had the lease extended, but for an unspecified period.

Then onwards, Mrs. Taylor was embroiled in a constant legal and battle of nerves with the government. In 1973, the same Federal Land Commission reconsidered its earlier order and cancelled the lease. But it then changed its decision once again in 1974 until it finally revised its decision against Mrs. Taylor in 1976. It was not that she was a nobody. She was well connected with the local elite and her old servants talk about her friendship with people such as Begum Abida Hussain. This was probably because both women were inheritors of jagirs (land given by the colonial state), especially land for stud farms. Mrs. Taylor’s farm was known for its horses that were not only provided to the army but exported as well. But unlike Begum Abida, Mrs. Taylor did not have the benefit of a family to at least help her fight off the other feudal or big landowners of the area.

The musical chairs around her land continued as the land commission changed its decision and gave her the lease until 1979. These were the years when other actors such as the Remount Depot also jumped into the fray and insisted that her lease had finished and she must vacate the property. Mrs. Taylor took recourse to the legal system and was given a stay order that continued until 1989. While she continued to contest the application of martial law regulation 115 it was no longer applicable on her as martial law had been lifted. The chief justice of the Lahore High Court referred the matter to the deputy commissioner of Okara for arbitration who ordered the land to be surrendered to the provincial government.

It was one early morning in 1991 when a few people, including a lawyer, a shopkeeper, a driver and a labourer led by civil and military state functionaries forced into Mrs. Taylor’s farmhouse. Although there was no resistance from the 80-year-old woman, except for a refusal to leave her home, she was beaten so badly that she had to be admitted to hospital. This was not a revolutionary resistance against a colonial master by landless peasants. She was at peace with them until her death in sad conditions in 1994.

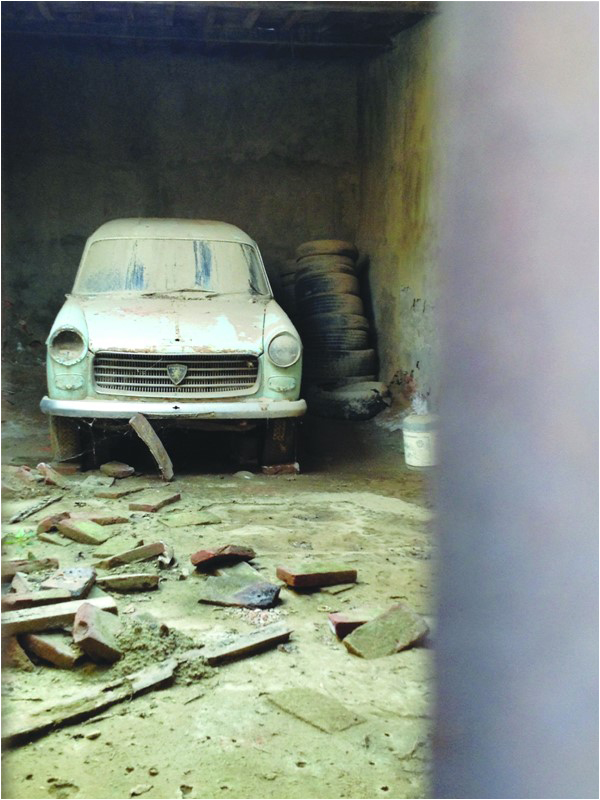

While the Okara Remount depot absorbed the farm and the Punjab government didn’t hear of it ever again, little was done to her house at least until 2013 when I visited it and saw her old Peugeot parked in a locked garage and her books strewn in the rooms. The people who ransacked her house in 1991 had probably taken away anything of value, leaving what they had deemed useless: the sofas, books, piano, car and grandfather clock.

At her grave outside her home, I wondered why she didn’t leave. While walking through the corridors of an empty Renala House it occured to me that Mrs. Taylor’s life story was not just about control of land. She could have gone to Zimbabwe (Rhodesia) where she also had property, the control of which she had given to her only son John Vanrenan Taylor through a general power of attorney signed in Lahore on April 14, 1980. In 1991, the conditions for white landowners in Zimbabwe had toughened, but it was not the end of the line for her there as it had been in Pakistan. So, why did she choose to die in Renala? What is it that brings John Taylor Jr. back to the town where he only comes and visits the houses of old servants?

Was it that Renala was home for the mother and son as if they had nowhere else in the world? But could they consider a place home when it was not their homeland? Mrs. Taylor’s life opens up a mystery about what is that you can or cannot call home. Is it where you are born or your ancestors come from, or a place where you have lived and invested your emotions? How does it feel to be chucked out of your home, which is not your homeland, but was as good as your own?

Can we confess our inability to think of home from outside the confines of homeland, nation-state and patriotism?

Ayesha Siddiqa is an author and independent scholar and can be reached at www.drayeshasiddiqa.com she tweets as @iamthedrifter

There were signs that people had rummaged through her property but it still smelt of her. Walking around her ample bungalow, I wondered who she had been. Why did she not move away when the time was right? Why did she choose to be buried thousands of miles away from home, in a land where she was humiliated and even physically harassed during her last days?

In 1991 when a few people forced into Mrs. Taylor's farmhouse. Although there was no resistance from the 80-year-old woman, except for a refusal to leave her home, she was beaten so badly that she had to be admitted to hospital

It was sheer accident that I came upon Mrs. Hazel Deneys Taylor’s grave outside her farmhouse in Renala Khurd. I was searching for signs of radicalism in Punjab and did not expect to find the last abode of a white British woman in the hometown of Zakiurehman Lakhvi, the Lashkar-e Tayyaba, Jammat-ud-Dawa bigwig. Indeed, when Lakhvi went to fight his first battle in Afghanistan on the side of the first generation of Afghan warlords, Mrs. Taylor was still alive and in control of her farm. She seems to have lived peacefully with the people in an area which is one of the hubs of ahl-e Hadith in central Punjab. But then, the organic ahl-e Hadith of the area was not violent. In fact, the Lakhvis are a big clan and some of the notables contest elections and act as local pirs, despite being ahl-e Hadith. Could it be that they did not want to hurt an elderly woman who had spent almost her entire life in that area?

When the British established the irrigation system in Punjab and introduced the Colonization of Land Act 1912, one of the first leases in the region was given to one Major Deneys Henry Vanrenen in 1915. This is probably where Hazel had come to live with her parents. Compromising villages 20/1RB, 21/1RB, 22/1RB, 23/1RB, 13A/1R, and 14A/1R, the lease was from 1915 to 1935. The 20-year lease was later extended for another 10 years until 1945. However, Major Vanrenen died in 1938 and his daughter Hazel, along with her husband Col. John F. L. Taylor, managed the lease. It appears from records of the chartered accountant firm A. F. Ferguson & Co. that both husband and wife held shares in Renala Estate Limited.

Unmindful of the local political conditions, the couple developed the farmland, and facilitated the building of roads, the Renala railway station, a police station, and stables for horses, a paddock, and a model village. Impressed by their performance, the colonial state extended the lease for another ten years with the promise that the Taylors would be able to buy the farm at the end of the ten-year period.

But things changed soon after. The farm took a hit due to the torrential rainfall in 1948 when 4,500 out of 7,723 acres became waterlogged. But this was just the beginning of problems for the Taylors, especially after the lease expired in 1955 when other stakeholders in the area challenged the ownership. However, the then deputy commissioner of Multan, under whose control the land fell, Sardar Atta Mohammad Laghari, decided in favor of the Taylors and offered them an extension of the lease for another 10 years.

Eventually, the lease was extended from 1969 to 1979, a year after Col. John Taylor’s death in 1968. This extension did not ease pressure from Mrs. Taylor as soon after, in 1971, President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto ordered the confiscation of the land under martial law regulation 115. But the then Federal Land Commission that was moved in this case gave its judgment that regulation 115 did not apply on this land. Consequently, Mrs. Taylor had the lease extended, but for an unspecified period.

Then onwards, Mrs. Taylor was embroiled in a constant legal and battle of nerves with the government. In 1973, the same Federal Land Commission reconsidered its earlier order and cancelled the lease. But it then changed its decision once again in 1974 until it finally revised its decision against Mrs. Taylor in 1976. It was not that she was a nobody. She was well connected with the local elite and her old servants talk about her friendship with people such as Begum Abida Hussain. This was probably because both women were inheritors of jagirs (land given by the colonial state), especially land for stud farms. Mrs. Taylor’s farm was known for its horses that were not only provided to the army but exported as well. But unlike Begum Abida, Mrs. Taylor did not have the benefit of a family to at least help her fight off the other feudal or big landowners of the area.

The musical chairs around her land continued as the land commission changed its decision and gave her the lease until 1979. These were the years when other actors such as the Remount Depot also jumped into the fray and insisted that her lease had finished and she must vacate the property. Mrs. Taylor took recourse to the legal system and was given a stay order that continued until 1989. While she continued to contest the application of martial law regulation 115 it was no longer applicable on her as martial law had been lifted. The chief justice of the Lahore High Court referred the matter to the deputy commissioner of Okara for arbitration who ordered the land to be surrendered to the provincial government.

It was one early morning in 1991 when a few people, including a lawyer, a shopkeeper, a driver and a labourer led by civil and military state functionaries forced into Mrs. Taylor’s farmhouse. Although there was no resistance from the 80-year-old woman, except for a refusal to leave her home, she was beaten so badly that she had to be admitted to hospital. This was not a revolutionary resistance against a colonial master by landless peasants. She was at peace with them until her death in sad conditions in 1994.

While the Okara Remount depot absorbed the farm and the Punjab government didn’t hear of it ever again, little was done to her house at least until 2013 when I visited it and saw her old Peugeot parked in a locked garage and her books strewn in the rooms. The people who ransacked her house in 1991 had probably taken away anything of value, leaving what they had deemed useless: the sofas, books, piano, car and grandfather clock.

At her grave outside her home, I wondered why she didn’t leave. While walking through the corridors of an empty Renala House it occured to me that Mrs. Taylor’s life story was not just about control of land. She could have gone to Zimbabwe (Rhodesia) where she also had property, the control of which she had given to her only son John Vanrenan Taylor through a general power of attorney signed in Lahore on April 14, 1980. In 1991, the conditions for white landowners in Zimbabwe had toughened, but it was not the end of the line for her there as it had been in Pakistan. So, why did she choose to die in Renala? What is it that brings John Taylor Jr. back to the town where he only comes and visits the houses of old servants?

Was it that Renala was home for the mother and son as if they had nowhere else in the world? But could they consider a place home when it was not their homeland? Mrs. Taylor’s life opens up a mystery about what is that you can or cannot call home. Is it where you are born or your ancestors come from, or a place where you have lived and invested your emotions? How does it feel to be chucked out of your home, which is not your homeland, but was as good as your own?

Can we confess our inability to think of home from outside the confines of homeland, nation-state and patriotism?

Ayesha Siddiqa is an author and independent scholar and can be reached at www.drayeshasiddiqa.com she tweets as @iamthedrifter