Democracy can be a tricky term to explain in a political structure like the one that endures in Pakistan. Defining it can be as facile and effortless as Abraham Lincoln did; “government of, by and for the people”.

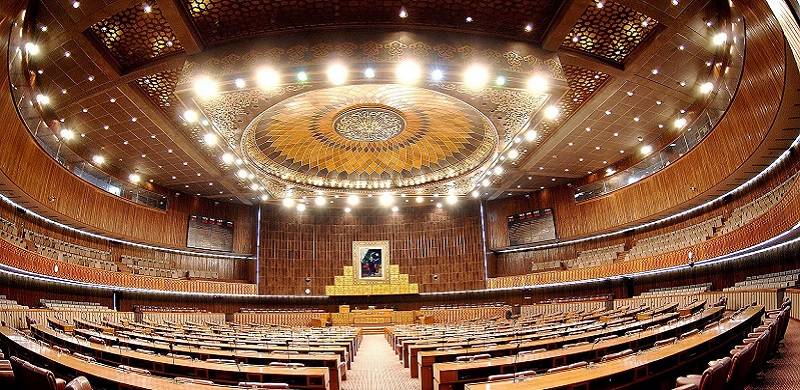

It can be turned into an arduous task overnight by creating complications such as whether an elected member of parliament can vote according to the desire of the people whose votes in the first place jettisoned him to the prestigious lawmaking body. A simple constitutional procedure of summoning the National Assembly, tabling a no-confidence motion followed by a vote of members has been twisted and tangled with the partisan approach of the supposedly unbiased and neutral Speaker of the House in an attempt to force an outcome of choice through a rather rugged interpretation of constitutional provisions.

In a bid to quell the no-confidence motion using the loopholes in the law, a presidential reference has been filed in the Supreme Court of Pakistan pursuant to Article 186 of the constitution of Pakistan that seeks the advisory opinion of the apex court to clarify the scope and raison d’être of Article 63-A. The provision in question that was piloted by the Nawaz Sharif government back in 1997 through the fourteenth amendment aimed “to prevent instability in relation to the formation and functioning of [the] Government”. Lately amended by the eighteenth amendment, Article 63-A has caused a dividend amongst the corridors of politics and the legal profession.

The battle of numbers that started from the parliament after a no-confidence motion was submitted by the opposition alliance under Article 95 has now made its way to the court where the ultimate fate of defecting members would be decided by a five-member larger bench headed by Chief Justice of Pakistan.

Article 63-A provides for possible disqualification of defecting parliamentary member if he/she resigns from the membership of their political party and join hands with another or if such a member votes or abstains from voting in the House contrary to any direction issued by the Parliamentary Party to which the member belongs, in relations to, the election of Prime Minister or Chief Minister, vote of confidence or vote of no-confidence and a Money Bill or a Constitution Amendment Bill.

Article 63 was amended to ward-off the horse-trading and floor-crossing of turncoat members. This provision also vests the power to the head of the political party to determine whether any of the member lawmakers have been involved in violation of Article 63-A. The head of the party then shall convey the decision to the chairman Senate, Speaker National Assembly, or Provincial Assembly (presiding officer), wherever the case lies. The presiding officer will convey this to the Chief Election Commissioner within two days and notification of de-seating the unlucky member within seven days would be expected from the Election Commission of Pakistan. The defection article was amended by the eighteenth amendment and empowered the “political party” head with lodging de-seating reference, something that was the parliamentary party head’s prerogative previously (political party head may not be an elected member of parliament). Although the broad definition of defection remains the same, after the eighteenth amendment, the Election Commission was empowered to turn down or confirm the reference submitted by the political party head, and the decision of EC is now subject to review by the judiciary.

The presidential reference seeks opinion from the SC on the interpretation of Article 63-A prior to the no-confidence motion vote initiated by the opposition alliance against Khan’s premiership. The reference asks whether a suitable interpretation of Article 63-A would mean that “Khiyanat” (dishonesty) by way of defections warrants no pre-emptive action save de-seating the member as per the prescribed procedure with no further restriction or curbs from seeking election afresh.” or a second interpretation should be followed that “visualises this provision as prophylactic, enshrining the constitutional goal of purifying the democratic process, inter alia, by rooting out the mischief of defection by creating deterrence, inter alia, by neutralising the effects of the vitiated vote followed by lifelong disqualification for the member found involved in such constitutionally prohibited and morally reprehensible conduct.”

The presidential reference also seeks advisory opinion on the aftermath of defections that whether such members of the parliament would be disqualified for life or whether their “tainted” votes should be given equal weightage or counted at all.

If the second interpretation is confirmed by the larger bench along with no-weightage given to “tainted” votes rhetoric, one contends what pertinence would Article 95 have at all. A political party’s Prime Minister with a simple majority in the House would never be subject to no-confidence motion, thus, effectively and only making the Article relevant in a coalition government setup. The only path leading to the elimination of a Prime Minister holding a simple majority in the House, as suggested by the Attorney General of Pakistan, would be for the defecting members to resign from their seats, join another party or contest independently, win the by-election and reduce the simple majority to force the government to seek coalition partners or let go of the reins of power.

This seems an impracticable solution that requires some sense. It is inconceivable that the draftsmen of the constitution just wanted Article 95 to be there to feed some formality. Lifelong disqualification is also something that doesn’t seem fair for a mere dissent that a member holds.

The debate of “democratic values” also spirals its way in this debacle. Many from echelons of the legal and political profession are of the view that a member of parliament represents the will of the people of their constituencies and therefore, it is an inherent right of any member to vote in a way that gives effect to this will. A lifelong disqualification that may follow (if the second interpretation is accepted) will further affect the very essence of democracy that should encourage differences of views and opinions. If one loses confidence in their Prime Minister that was elected by their votes then they shouldn’t be punished with a sanction that will haunt them for the rest of their lives and put a full stop to their political career.

Article 63-A may be a difficult one to interpret in many ways. It requires striking a balance between two problems; the floor-crossing that provides fuel to illegitimate practices like horse-trading and on the other hand, one’s right to vote independently without a sword of disqualification hovering over the heads as a suspended sentence.

It can be turned into an arduous task overnight by creating complications such as whether an elected member of parliament can vote according to the desire of the people whose votes in the first place jettisoned him to the prestigious lawmaking body. A simple constitutional procedure of summoning the National Assembly, tabling a no-confidence motion followed by a vote of members has been twisted and tangled with the partisan approach of the supposedly unbiased and neutral Speaker of the House in an attempt to force an outcome of choice through a rather rugged interpretation of constitutional provisions.

In a bid to quell the no-confidence motion using the loopholes in the law, a presidential reference has been filed in the Supreme Court of Pakistan pursuant to Article 186 of the constitution of Pakistan that seeks the advisory opinion of the apex court to clarify the scope and raison d’être of Article 63-A. The provision in question that was piloted by the Nawaz Sharif government back in 1997 through the fourteenth amendment aimed “to prevent instability in relation to the formation and functioning of [the] Government”. Lately amended by the eighteenth amendment, Article 63-A has caused a dividend amongst the corridors of politics and the legal profession.

The battle of numbers that started from the parliament after a no-confidence motion was submitted by the opposition alliance under Article 95 has now made its way to the court where the ultimate fate of defecting members would be decided by a five-member larger bench headed by Chief Justice of Pakistan.

Article 63-A provides for possible disqualification of defecting parliamentary member if he/she resigns from the membership of their political party and join hands with another or if such a member votes or abstains from voting in the House contrary to any direction issued by the Parliamentary Party to which the member belongs, in relations to, the election of Prime Minister or Chief Minister, vote of confidence or vote of no-confidence and a Money Bill or a Constitution Amendment Bill.

Article 63 was amended to ward-off the horse-trading and floor-crossing of turncoat members. This provision also vests the power to the head of the political party to determine whether any of the member lawmakers have been involved in violation of Article 63-A. The head of the party then shall convey the decision to the chairman Senate, Speaker National Assembly, or Provincial Assembly (presiding officer), wherever the case lies. The presiding officer will convey this to the Chief Election Commissioner within two days and notification of de-seating the unlucky member within seven days would be expected from the Election Commission of Pakistan. The defection article was amended by the eighteenth amendment and empowered the “political party” head with lodging de-seating reference, something that was the parliamentary party head’s prerogative previously (political party head may not be an elected member of parliament). Although the broad definition of defection remains the same, after the eighteenth amendment, the Election Commission was empowered to turn down or confirm the reference submitted by the political party head, and the decision of EC is now subject to review by the judiciary.

The presidential reference seeks opinion from the SC on the interpretation of Article 63-A prior to the no-confidence motion vote initiated by the opposition alliance against Khan’s premiership. The reference asks whether a suitable interpretation of Article 63-A would mean that “Khiyanat” (dishonesty) by way of defections warrants no pre-emptive action save de-seating the member as per the prescribed procedure with no further restriction or curbs from seeking election afresh.” or a second interpretation should be followed that “visualises this provision as prophylactic, enshrining the constitutional goal of purifying the democratic process, inter alia, by rooting out the mischief of defection by creating deterrence, inter alia, by neutralising the effects of the vitiated vote followed by lifelong disqualification for the member found involved in such constitutionally prohibited and morally reprehensible conduct.”

The presidential reference also seeks advisory opinion on the aftermath of defections that whether such members of the parliament would be disqualified for life or whether their “tainted” votes should be given equal weightage or counted at all.

If the second interpretation is confirmed by the larger bench along with no-weightage given to “tainted” votes rhetoric, one contends what pertinence would Article 95 have at all. A political party’s Prime Minister with a simple majority in the House would never be subject to no-confidence motion, thus, effectively and only making the Article relevant in a coalition government setup. The only path leading to the elimination of a Prime Minister holding a simple majority in the House, as suggested by the Attorney General of Pakistan, would be for the defecting members to resign from their seats, join another party or contest independently, win the by-election and reduce the simple majority to force the government to seek coalition partners or let go of the reins of power.

This seems an impracticable solution that requires some sense. It is inconceivable that the draftsmen of the constitution just wanted Article 95 to be there to feed some formality. Lifelong disqualification is also something that doesn’t seem fair for a mere dissent that a member holds.

The debate of “democratic values” also spirals its way in this debacle. Many from echelons of the legal and political profession are of the view that a member of parliament represents the will of the people of their constituencies and therefore, it is an inherent right of any member to vote in a way that gives effect to this will. A lifelong disqualification that may follow (if the second interpretation is accepted) will further affect the very essence of democracy that should encourage differences of views and opinions. If one loses confidence in their Prime Minister that was elected by their votes then they shouldn’t be punished with a sanction that will haunt them for the rest of their lives and put a full stop to their political career.

Article 63-A may be a difficult one to interpret in many ways. It requires striking a balance between two problems; the floor-crossing that provides fuel to illegitimate practices like horse-trading and on the other hand, one’s right to vote independently without a sword of disqualification hovering over the heads as a suspended sentence.