Eqbal Ahmad grew up in the era of the anti-colonial movement, in the summer of 1947, when India and Pakistan became two independent nations from the yoke of British colonialism. Ironically, the fate of Palestine was enveloped during the same period under the aegis of settler colonialism in 1948 in the formation of the state of Israel. Since then, Palestinian tragedy still haunts the collective consciousness of people across the world.

Eqbal was born in colonial India and grew up in Pakistan rose to become a rare internationalist and a man of impeccable knowledge of history and world politics. From Algeria to Vietnam, he was everywhere. The man was a towering intellectual and an inscrutable genius but above all truly an organic intellectual in the Gramscian sense.

He was one of the sanest voices for the Palestinian cause, not just from a South Asian standpoint but globally. Eqbal was not just a friend of Palestinians but a critical insider who didn’t mince in criticising the failures of the Palestinian liberation movement. To him, the failure of the Palestinian liberation movement in particular and the Arab liberation movement, in general, was largely due to its political and organisational limitations. Eqbal believed that the Arab liberation movement didn’t “go beyond the phase of radical bourgeois nationalism.” For Eqbal, Arab regimes were bourgeoisie nationalist regimes and were regressive, feudal and lacked functioning organisational capacity - and thus ended up following the subservience of preceding regimes to colonial, Western powers.

Eqbal Ahmad, a true friend of Palestinians, was also one of the hard critics of the Palestinian authority and their failures, particularly their inconsistencies in ideology and lack of a proper framework for Palestinians in their social, political and economic life. The failure to comprehend ideology, as Eqbal writes, also leads to intellectual and organisational failure. For Eqbal, Palestine must have what Edward Said calls "discipline of details" - how deeply you know your adversary, their strengths as well as their vulnerabilities. Eqbal’s vision for a free Palestine was against any militaristic or bureaucratic mindset but rather nurturing the ‘human material’ that will lead to success. He was not against confronting brute force, but criticised the absence of tactical force used by the PLO.

He cautioned on the principle of the invisibility of revolutionary soldiers, cadres and organisations that the Palestinian liberation movements hastily and often unthinkingly developed. He never veiled his sharp tone in understanding the geopolitics of American imperialism.

For Eqbal, one of the biggest fallacies in the unresolved Palestinian question has been the US foreign policy in the Middle East and its unconditional support to the Jewish state of Israel since its formation in 1948. Eqbal had a nuanced notion of how geography shapes history. For him, US support to Israel was inherently a ‘Mediterranean strategy’ to maintain their hegemony over the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean – rather than what historians like Bernard Lewis thought with their notion of a shared common interest of Judaeo-Christian heritage.

However, Christian Zionism in the US has been a great supporter of the Zionist regime of Israel and a huge influence in shaping US foreign policy in the Middle East even after the end of the Cold War. This, somehow, Eqbal failed to acknowledge. Nevertheless, he was a rare intellectual, who understood the deep notion of the functionalities of settler colonialism and its impact on the people who are at the receiving end, in this case, were Palestinians facing dispossession and exclusion from their native land, water, and other resources.

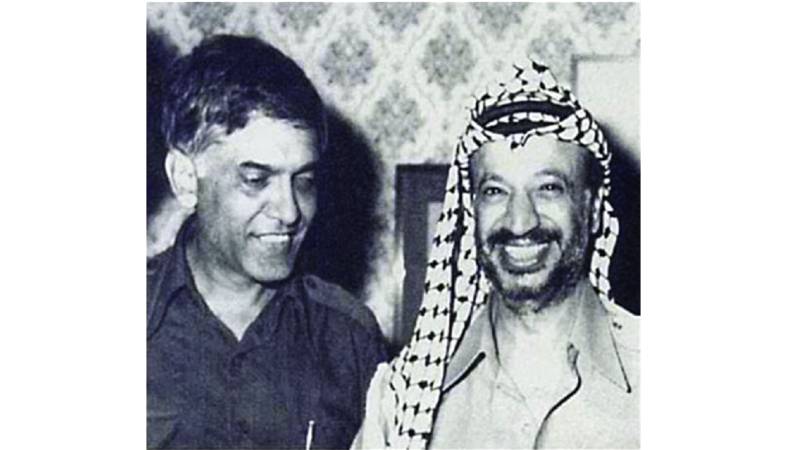

Eqbal was perhaps the only South Asian intellectual after Gandhi whose sane voice was hailed by Arabs in general. He was very close to Arafat and a great Samaritan to intellectual voices for the Palestinian cause in the United States, particularly Edward Said and Noam Chomsky. He reminded Palestinians about the need for documentation.

He was critical of how Israel became the first settler state to have resolved its 'native problem' from the very beginning of its existence with the help of revisionist historians and on the contrary, there was not much response from Palestinians and thus organised settler colonialism making it easy for Israel and the Zionist movement. He felt that the June 1967 war boosted for a while the badly damaged Palestinian and Arab morale, and it imposed the question of Palestine upon the consciousness of the world. Beyond that, it failed. He had cautioned Arafat on how Israel and the Zionist movements organised campaigns to get the Soviet Jewry into Israel and explained how the Palestinian leadership could not afford to ignore this extraordinary campaign to offset the demographic burden of the Zionists' 1967 conquest. Eqbal was critical of the so-called Oslo peace process. For him, Oslo-1 was a “peace of the weak.”

The last time Eqbal met Arafat was in Tunisia, after the PLO had been driven out of Lebanon by the invading Israeli army. Arafat was understandably depressed and barely followed Eqbal when he urged the PLO to recognise Israel, but then insisted on asking which Israel it should recognise.

Is it the Israel of 1948? Is it the Israel of the 1947 partition plan? Is it the Israel of 1948 that expanded three times more? Is it the Israel of the 1967 war? Is it the Israel of the Israeli imagination? This is because Israel is the only country today that has refused to announce its boundaries.

For Eqbal, peace is impossible with Zionists but then Palestinians need to develop a viable, acceptable peace proposal that die-hard Zionists may not accept, but the world, as well as decent Israeli opinion, could not afford to reject.

To him Jerusalem as the capital of Israel was unacceptable but an ancient heritage shared by Arabs and Jews meant that its protection should be a joint responsibility. That somehow, he was offering his advice to accept the status of Israel in its democratic form. Perhaps the most famous Palestinian voice in the world has been Edward Said. It was Edward Said who brought Eqbal Ahmad to Yasser Arafat and the Palestinian Executive Committee in Beirut and even when PLO had to move to Tunis in 1982. Said and Eqbal were close friends.

For Said, Eqbal was the most original anti-imperialist, an angry Asian whose incorruptible ideals made him a profound talker with a formidable knowledge of history, religion, and nationalism and somebody who was truly an internationalist in every sense as his interventions whether NATO’s intervention in Kosovo NATO Europe, America, Bosnia, Chechnya, South Lebanon, Vietnam, Iraq, Algeria or the Indian sub-continent reflects his dedication against the pervasive human cruelty and the Us vs Them. For Said, Eqbal was a combatant who lost personal achievement (remained an untenured professor for most of his life due to his uncompromising position on issues he took up). An organic intellectual whose submissions, and idealism in dealing with subjects that confront us all; questions of liberation and justice.

Said, in his memoirs of his encounters and friendship with Eqbal, wrote that Eqbal’s heroic defence, his unstinting sense of solidarity with my people, the Palestinians was rare. For many refugees, camp dwellers and wretched of the earth who have been forgotten by their leaders and their fellow Arabs and Muslims, Eqbal was one of their guiding lights. As Said used to call Palestine, a thankless cause., it is the cruellest, most difficult cause to uphold, not because it is unjust, but because it is just and yet dangerous to speak about as honestly and concretely as Eqbal did. For Said, Eqbal always spoke the language of “WE” as his authentic best, a point of his creative analysis.

On May 11, 1999, at 67, Eqbal Ahmad, a rare intellectual and most ardent South Asian voice for Palestinians passed with colon cancer in his home country Pakistan. Editorials and newspaper columns paid homage to a voice of the third world for Palestinians a fearless intellectual who was truly an internationalist. Al-Ahram paid his homage to him as “Palestine has lost a friend”. The New York Times writes he “woke up America’s conscience” and The Economist described him as “a revolutionary and intellectual who was the Ibn-Khaldun of modern times.” In his obituary on Eqbal, Edward Said wrote, that he was that rare thing, an intellectual unintimidated by power or authority, a sophisticated man who remained simply true to his ideals and his insights till his last breath.

Eqbal was prophetic in his voice and against any hypocrisy and dogmatism. He used to remind us, “the moment you find that your truth clashes with what is being peddled as their( media) intervene. To learn, look for alternative sources, for without alternative sources, without pluralism, there is no democracy.”

The sane voice from a rooted cosmopolitan still finds his honorary place in the struggle for the honour of Palestinians.