District Kurram with an area of 3,380 square kilometres and a population of 808,102 inhabitants has recently hit the headlines in national and international media. Its geo strategic location, ever volatile Shia-Sunni demographic equation, difficult terrain, lush green and fertile river valley, active footprints of terrorism, huge cashes of weapons, history of foreign involvement has enhanced its relevance since ages. In recent history, starting from the second Anglo-Afghan War in 1878, when Major General Roberts caused a historic defeat to Afghans at Peiwar Kotal by making his memorable night march and flank attack; Kurram has worked as lynchpin during the American-sponsored Afghan war against the then USSR, and later in the US war on terror.

Having a 192 km long boundary in the Durand Line, adjoining provinces of Nangarhar, Logar, Khost, and Paktia of Afghanistan and common borders with terrorism-affected districts of Khyber, Orakzai, Hangu and North Waziristan; Kurram forms a thin wedge about 65 miles long from Thall, and in parts not more than 10 miles broad, running into Afghanistan. Its western-most border crossing at historic Pewar Kotal, also called Givi crossing, just 65 miles away from Kabul; is the closest border crossing of Pakistan with the Afghan capital. The district is administratively divided into three tehsils, namely Upper Kurram having Parachinar as headquarters, Lower Kurram and Central Kurram; both of the latter having tehsil administrators’ seats in Sada.

The district headquarters at Parachinar is a famous town of about 55,000 inhabitants; mostly Turi and Bangash; in the Upper Kurram. Being the headquarters of the legendary Kurram militia and seat of the political agents and epoch-making Durand Line Commission, Parachinar holds immense importance for Pakistan because of its strategic location, its proximity to Central Asian republics and having a natural shield of snowcapped peaks of the Koh e Sufaid, also called Spin Ghar. The total population of Upper Kurram is 278,909: about 83% of them are Shia while the remaining 17% of the population consists of bordering Sunni tribes of Mangal, Muqbal, Jandran, Jaji, Akhroti and Bangash. Home to four border crossings namely Gavi, Kharlachi, Borki and Inzarki; Upper Kurram is hub of smuggling of animals, medicine, tractors, motorcycles, weapons, drugs and most importantly that of humans.

Lower Kurram; starting from Spin Thall to Amalkot; having two border crossings at Sharko and Shahdanodand with Khost province of Afghanistan; occupies a fertile narrow valley across the river Kurram; with a population of 153,133. Inhabited by major tribes of Bangash, Turi, Alisherzai, Mangal and Zeemushat and making a Shia-Sunni ratio of 35-65, Lower Kurram is a comparatively peaceful area. Lower Kurram shares its administrative seat with Central Kurram at Sadda . Absence of fencing and negative deviation for about 10 kilometres near Paloseen in Jaji Maidan make Lower Kurram vulnerable to smuggling and crossing of other anti-state elements.

With an area of 1,470 sq km and a population of 376,060 persons; Central Kurram is the largest tehsil. Inhabited by four major Sunni tribes of Parachamkani, Masozai, Alisherzai and Zeemushat. Occupying the difficult mountainous terrain along the borders with Afghanistan, Khyber, Orakzai and Hangu, Central Kurram has suffered the most. Besides having a history of training centres for Mujahideen during Afghan war, it worked as safe haven for Taliban after their expulsion from the well-known tunnel complex of the Tora Bora mountains and for the Haqqani Network of TTP during Operation Rah-e-Nijat in North Waziristan. Central Kurram has scarce road infrastructure, meagre facilities for clean water, electricity, schools and hospitals and is the least developed, most deprived area of district Kurram. Marginalisation of Central Kurram can be gauged by the fact that it has not a single higher secondary school; despite being the largest tehsil in area and population. Illiteracy, poverty, large household size and total absence of communication signals further aggravate the social crisis.

Primarily Kurram is a land of contradictions in which courage blends with stealth, the basest treachery with the most touching fidelity, intense religious fanaticism with avarice playing false to the faith, a lavish hospitality with an irresistible propensity for thieving. It is a place of paradoxes; Sunni Sada versus Shia Parachinar; the fertile valley of river Kurram versus undulating dry hills of lower and central Kurram; sharp sun shine in foots of snow covered Koh e Safed; in local vernacular Gido versus Pewar.

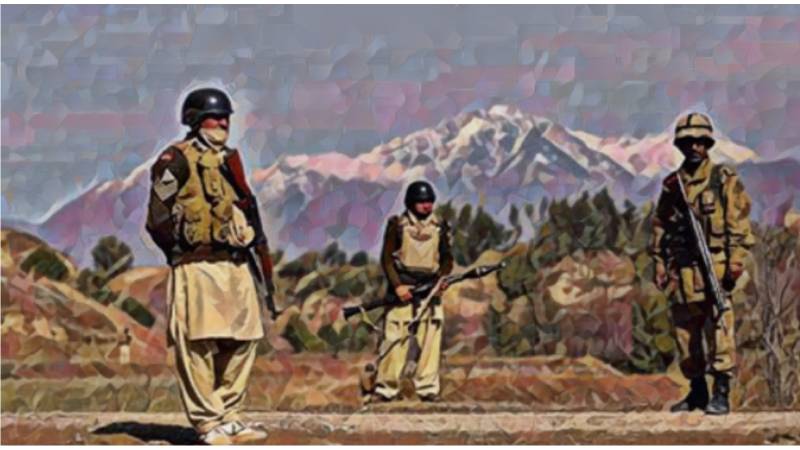

Kurram’s geostrategic location has added to the sufferings and plight of its people. The district, especially Lower and Central Kurram, was used as a launching pad for Mujahideen in the US war against the Soviet military intervention Afghanistan. The area was flooded by American arms, ammunition and weapons, and, most importantly, by American-sponsored training camps. The Zia regime launched anti-Shia operation in Sada; the district’s Sunni capital; to purge it of the Shia minority and to teach Shia of Upper Kurram a lesson on their refusal to give passage to Mujahideen.

Fuelled by the US-funded Afghan war and Khomeini’s Islamist revolution in Iran, the ever fragile sectarian equation of Kurram has taken a huge toll on human life and sufferings. Starting from the 1960s, Kurram has witnessed a systematic wave of sectarian clashes in every decade.

The infrastructure of sectarianism is still green due to the blanket misuse of social media platforms, presence of trained fighters and caches of weaponry on both sides.

Kurram people are brave, fearless and simple sons of the soil. They are loyal to their land, to their religion, to the country and even to their grudges. They proudly narrate stories of sacrifices made by their forefathers for Pakistan. Vengeance, family feuds and vendetta still hold the sway. Uneven distribution of basic needs of life; medical and educational facilities has led to divergent fates for its people. People in Upper Kurram; being educated, employed and affluent are at par with people of any other settled district in KP. By contrast, he people of Lower and Central Kurram; being deprived and not properly educated, are marginalised.

The merger of the former Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) by the remarkable 25th amendment in the Constitution of Pakistan opened new vistas for the people. The new system has brought new departments, new challenges and new dreams. A transition period; full of suspicions and doubts, is going to end. And yet, the stakeholders of the old tribal system are too strong to be replaced so early.

The police and the courts; being drivers of the new system, are trying to perform their best. People have high hopes. Policing with poorly trained, disciplined and equipped Levies and Khasadar forces is the real challenge. There is a dire need for bringing in new blood through recruitments and training of the educated lot from the old personnel. Dedicated, competent and honest officers are the only hope to establish new departments on strong footings. To lure young officers from the Police Service of Pakistan (PSP) and Pakistan Administrative Services (PAS), all districts of the tribal areas need to be declared ‘Hard Areas’ for the service benefits that might make such a posting more attractive.

The people of Kurram are more sinned against than sinning. They are victims of the follies made by others on their land in the past. Viciously interwoven dark factors of historical legacy, tribal-cum-sectarian vendetta, perennial disputes on land and water resources, strategic location and involvement of international actors are contributors to the current plight of the area. Illiteracy, poverty, high birth rate, lack of resources and opportunities are the ‘blessings’ of history.

A holistic effort encompassing across the board de-weaponisation, strengthening of the criminal justice system, equal distribution of resources and opportunities based on local inclusiveness and participation of women – only such policy focus can bring about meaningful change. Initiatives need to be taken on the part of the government, locals, NGOs, media and intelligentsia. But at the end of the day, it has to be borne in mind that the locals, supported by political forces and the government, will be the true drivers of the new system. And that is how it ought to be.