In any species, three aspects combine to encourage a viable mating system: paternal care, resource management, and partner choice. The idea behind interweaving one’s life with another human being is to positively influence one’s happiness, health, and a sense of uniqueness. Seeking a life partner can also be a part of human character to desire companionship; even before words and communication were invented, Neanderthals formed ties, had families, and enjoyed those connections. Nonetheless, is it possible, for one human being to achieve a perfect understanding of another? We convince ourselves that we know the other person well, but do we really know everything about them? We all want the words “happily ever after” scrawled on the end screen of our lives, but I often see individuals spending countless hours and currency in psychotherapy, trying to make sense of their marriages and relationships. Genuine apprehensions, therefore, raise their head, "What do these relationships do for us that we can’t do ourselves?" or “Does a successful, and independent person really need a partner to be happy?”. These questions might sound simplistic, but trying to answer them quickly might not be wise.

Human relationships are complicated. Women were traditionally involved with men in dependent relationships based on defined roles, where men provided financial support in exchange for producing heirs and lifelong caretaking. As cultures evolved and women assumed other roles in association with men, a new relationship convention emerged and roles were redefined. Without the need for financial support, what could this new partnership look like in the relationship equation? People have their own answers to this question depending on where they live and what works for them. These could be anything from nurturing a family, companionship, and friendship to having someone help you grow into the best version of yourself, or having someone just be there for you for the good and the bad. Relationships remain a leap of faith at some level, due to complex reasons. For instance, there is something exceptionally overwhelming about having someone love you for who you are, imperfections and all. You can, of course, choose to love yourself and you can be your best friend, but it is more formidable to appreciate that you can be your worst self and someone is OK with that, for better or for worse.

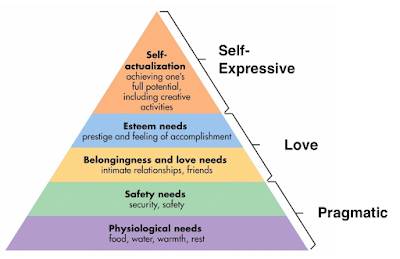

In his book, Eli Finkel proposes a paradigm of relationships aligned with Abraham Maslow's “Hierarchy of Needs”.

Finkel's relationship paradigm imposed atop Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

He describes three eras of relationships. The first era of "pragmatic-based relationships" served to meet the lower tiers of Maslow's Hierarchy - to fulfill physiological and safety needs. As societal advances allowed such needs to be more easily satisfied, "love-based relationships" evolved. These relationships fulfilled the human needs for belonging, intimacy, and self-esteem. Relationships have ascended further up Maslow's Hierarchy since "self-expressive-based relationships" are now centered on the need that partners must achieve their full potential. It is important to note that the existence of a relationship at a higher tier does not preclude the necessity for a relationship to fulfill the more basic needs; it simply recognises the hierarchy of human needs. Not all contemporary relationships are self-expressive; some continue to be bonded by pragmatic forces, and others are fuelled by love. However, the presence of self-expressive relationships in modern society is becoming more common.

Those who abide by the “love map” theory believe that this inner wiring can largely be determined by our childhood experiences, including our relationships with our parents and other caregivers. This love map can spell out our longings for distinct personality types, appearances, smells, etc

Robert Sternberg is the most prominent theorist on love and relationships. He presented the triangular theory of love that is based on intimacy, passion, and commitment. He states that a relationship is most stable when it involves two or more of the characteristics. Once we understand what types of relationships we can have, we go about choosing who to have them with. Do “opposites attract” or do “birds of a feather flock together”? There is evidence to suggest that both can turn out to be all right. Most of us choose someone based on things that we have in common. However, we can also choose people based on our needs: an unorganised person may want someone who is organised, a talker may want a listener, or an adventurer may want someone more stable to help balance them out. According to research, who we fall in love with, is also determined by our “love-map”, which is essentially a coding that exists in our minds. Those who abide by the “love map” theory believe that this inner wiring can largely be determined by our childhood experiences, including our relationships with our parents and other caregivers. This love map can spell out our longings for distinct personality types, appearances, smells, etc.

For some, the point of having a life partner is to have a witness for their lives. While there are plenty of people who can do life happily and successfully without a romantic partner, it is a different experience to do it together. For example, I like having someone around who gives me a look if I speak to a waiter unkindly or overtake someone sharply while driving. I believe it is important to have someone close who can challenge us from time to time but with compassion. Teenage children are very good at this, as they can get us to think about how we choose to live because they tend to question things. But they grow up and often leave home when we need them the most. For others, a romantic partner is as much about their experience outside the home as the one with them in it. Our experience out in the world improves after knowing there is someone at home who loves us no matter what. Having a partner is to have a mutual, and harmonised relationship with someone you love who accepts you exactly as you are and who loves you, faults and all. It is difficult under those circumstances not to grow as a person, not to have more courage, generosity, and love to give, not only to your partner but to everyone. We also have a relationship with someone not only because of how great they are but how great they make us feel. If you ask other people why they need a life partner, there might be as many answers as there are people.

Love and lust are sometimes confusing or used interchangeably. Science can rescue us by clarifying that romantic love is linked with the natural stimulant dopamine and to some extent with norepinephrine and serotonin, and feelings of male-female attachment are produced primarily by the hormones oxytocin and vasopressin. The latter two chemicals are associated with our ability to form memories of others and help us recognise other people for lasting attachments. These chemicals are also released, along with dopamine, during sex. Elevated levels of dopamine in the brain produce focused attention, as well as unwavering motivation and goal-directed behaviours, which are central characteristics of romantic love. Lovers are intensely focused on the beloved, often to the exclusion of all around them. They concentrate so relentlessly on the positive qualities of the adored one that they overlook his or her negative traits. Lust, on the other hand, is associated primarily with the hormone, testosterone, in both men and women. Men with high baseline levels of testosterone marry less frequently, have more adulterous affairs, commit more spousal abuse, and divorce more often. As a man’s marriage becomes less stable, his levels of testosterone rise. With divorce, his testosterone levels rise even more; single men tend to have higher levels of testosterone than married men.

On a planet of over eight billion people, it is quite a coincidence that so many soulmates are found in the same or next classroom. Yet the idea of a soulmate has persisted across civilisations and time periods. Hajimi Onishi, the Japanese philosopher, believes that there is something innate in our desire to believe in soulmates.

The idea of finding a soulmate, as a life partner, is supposed to serve as a soothing balm after a bad date or create a narrative to our love story. But, it is surprising how many people across various cultures believe in this myth, started by the Greek philosopher, Plato. He wrote that human beings had four arms, four legs, and two faces until Zeus, the god of sky, law, and order in Greek mythology, split them up in half as a punishment for their pride; and they are destined to walk the Earth searching for their other half. Similarly, Hindu traditions hold the concept of people having a karmic connection with certain souls; and in Yiddish, there is a term for predestined marriage partner “bashert”, that loosely translates to destiny. Thirteenth-century Persian poet, Rumi, masqueraded the notion that lovers do not finally meet, but that they were somehow into each other all along. Western literature is also replete with examples of lovers who were meant to be together, but the English poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, was the first to use the word “soulmate” in a letter he wrote in 1822. The irony is that Coleridge’s own love life was ill-fated, as he had married due to social pressures. He spent most of his life apart from his wife until they separated for good.

He believed what we like and dislike in another person are parts of our own self, projected onto others to be experienced as an acceptable reality. We fall in love because we long to escape from ourselves with someone beautiful, intelligent, and witty because we feel ugly, stupid, and dull

On a planet of over eight billion people, it is quite a coincidence that so many soulmates are found in the same or next classroom. Yet the idea of a soulmate has persisted across civilisations and time periods. Hajimi Onishi, the Japanese philosopher, believes that there is something innate in our desire to believe in soulmates. He points out that, for many of us, believing in a soulmate is a way of constructing a consistent narrative from the oftentimes chaotic and unpredictable experience of looking for love. This is particularly true when it comes to modern dating, which perhaps explains how the soulmate idea has evolved. In a time of overwhelming uncertainty, politically, environmentally, and socially, the soulmate myth promises that amidst the dizzying and often confusing landscape of dating apps, there is one match out there that will make sense of it all. It promises an anchor to modern life that many find appealing. People think a soulmate is our perfect fit, and that's what everyone would like to have. A true soulmate can also be a mirror - the person who shows you everything that is holding you back, the person who brings you to your own attention so that you can change your life for the better. In the final analysis, believing that you have found your soulmate might not be a bad thing after all - it stops you from worrying about looking for one.

When we are not in a relationship, we often fantasise about a life partner with whom we can do things together. On the other hand, when we are in a relationship, we are too busy complaining about the same partner, and forget what we could be relishing together. French philosopher, Jean-Paul Sartre, saw intimate relationships as being needy and possessive in their nature; and a means to experience parts of our self through another. He believed what we like and dislike in another person are parts of our own self, projected onto others to be experienced as an acceptable reality. We fall in love because we long to escape from ourselves with someone beautiful, intelligent, and witty because we feel ugly, stupid, and dull. He opined that we yearn for a perfect relationship, as a way of being completed by another person because we gain something we don’t have, whether it is comfort or to relieve ourselves of anxiety and insecurity. But, constantly being with the same disagreeable aspect of ourselves, makes us tired of seeing the familiar patterns being played out again and again. When these experiences are compounded, we feel even lonelier in a relationship than when we were single. All relationships have their highs and lows because we are all dealing with aspects of ourselves that we may not want to face, so rather than accepting those, we resist them and cause ourselves more problems…… (to be continued…)