How is the COVID-19 pandemic going to affect Pakistan’s economy? It is difficult to make precise predictions as there is still so much that is unknown. For example, why are mortality rates so much lower in South Asia as compared to Europe and USA? Is it because we have a younger population; is it because we have developed high levels of immunity due to the many diseases we are routinely exposed to; or has it something to do with Tuberculosis and the BCG vaccine? Despite these and other uncertainties it is worth looking at possible impacts and what actions may be required to minimize its negative effects.

First of all let us look at short term impacts. There is likely to be a sharp drop in domestic consumer demand. Expenditures on food, medical assistance and other essential items would rise but this would be more than offset by lower demand for consumer goods, apparel and services. This drop in demand will be compounded by foreign buyers delaying or cancelling orders; a fall in travel and tourism; and further drops in the stock market which would erode peoples’ wealth and their willingness to spend. There is also likely to be a fall in remittances due to layoffs and delayed salary payments to Pakistani workers in the Middle East and elsewhere.

Lower overall domestic consumer demand will have a negative impact on production and employment. It may be less severe in agriculture where demand for food and other products will remain high, and supplies will continue despite possible local problems related to restrictions on movement of outputs, inputs and labour. The drop may be larger in manufacturing but some companies may try to carry on operating, building up stocks of finished goods, rather than reduce production and lay off staff. The effects are likely to be most severe in the construction and small scale services sector where most of the labour force is hired on a daily wage basis.

On the supply side, there are also likely to be disruptions as there may be shortages of imported raw materials and spare parts. However, one of Pakistan’s key imports is fuel, and prices have dropped sharply. This should help but would require that the positive impact of lower international oil prices works its way quickly through to local consumers.

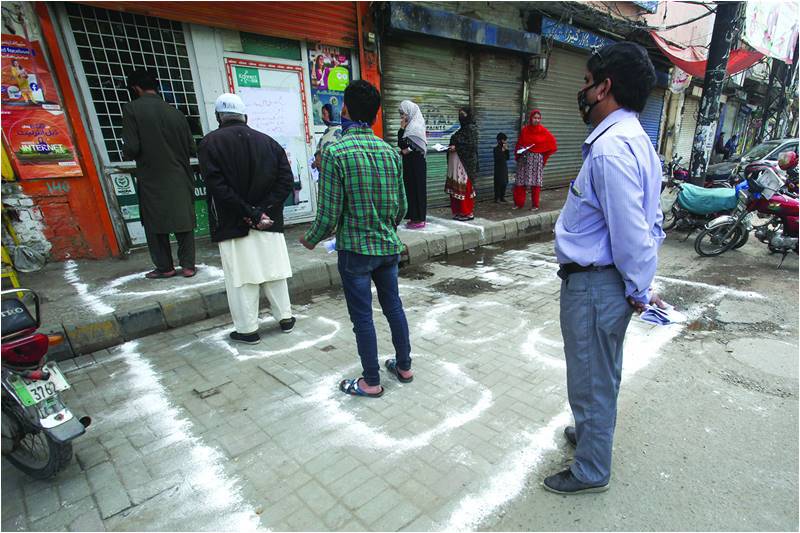

The severity and duration of the short term demand and supply impacts depends on the measures the government adopts to contain the spread of the virus. So far Sindh has taken the strongest actions. Other provinces and the federal government are also providing guidelines on reducing activities and movements. These measures are not as drastic as in India or some European countries, but would nevertheless have a severe negative impact on the economy. Most likely GDP would fall by more than 1.3 percent estimated by the World Bank and maybe even approach the over 5 percent-10 percent fall projected for several affected countries such as Italy and Spain. Such a fall would cause severe hardship, especially coming on top of a period of high inflation and slow growth. The impact will disproportionately fall on the poorest and weakest sections of the population, such as daily-wage workers and casual labour in activities such as transport, construction, the retail trade, and small hotels and restaurants

But let’s not forget that we Pakistanis are a resistant and strong people. And, in times of crisis, we tend to come together to help each other. This happened at the time of the 2005 earthquake and the 2010 floods when thousands of people volunteered their time, along with billions of PKRs, to help the needy. This time around as well, private citizens, civil society organizations and NGOs, as well as mosque committees and religious groups, are taking on much of the strain of helping the poorest. This includes direct help in cash and food items, continued salaries despite workers’ inability to come to work, and assistance with medical expenses.

However, it is also clear that private support mechanisms will not be able to fully cope. Moreover, such mechanisms tend to be relatively weak in rural areas as the scattered nature of the population makes it difficult to reach effected people. The government is already working to strengthen its social safety nets and in particular the Ehsaas program, the Utility Shops and the newly formed Tiger Force. In rural areas it should also involve police stations, health clinics, agriculture/livestock offices and the network created by the National Rural Support Programmes. All of these must be asked to provide logistic help for both medical assistance and to reach the rural poor with food and income support.

So what can the government do apart from relief related actions? It should use the two major policy instruments at its disposal – the rate of interest and the exchange rate. The State Bank needs to continue to cut interest rates. More importantly, it should require commercial banks to make corresponding decreases in interest rates on outstanding loans to consumers and businesses, and allow them to reschedule repayments. In order to facilitate increased liquidity, commercial banks should be allowed to reduce their statutory liquid reserves and deposits with SBP. At the same time, government should avoid efforts to bolster foreign exchange markets. In fact a slide in the PKR would help Pakistani exporters become more competitive in the face of falling global demand.

Government should also be proactive on calling on various development partners, particularly those with expertise in medical matters, food and nutrition security and social protection, to help design quick impact projects to cushion the poorest. It is worth mentioning that the Government is already accessing some of the funds set aside for the COVID-19 crisis by international agencies such as the World Bank (US$12 billion), the Asian Development Bank (US$6.5 billion) and the IMF (US$50bllion). A special role should be given to the World Food Programme which has much needed expertise in dealing with the crisis logistics, as well as in raising resources. The government should also continue its negotiations with creditors to write off debts or at least delay some of the debt service payments which amount to around 5% of GDP.

In addition, the government should try and take advantage of the price war among oil exporters, and the resulting lower prices. As mentioned above, these cuts should be passed on to consumers, particularly industrial and commercial users, through lower prices for fuel and electricity. There should also be cuts in diesel prices to help agriculture, industry and transporters.

As we move ahead, we need to keep in mind that this outbreak will run its course as other pandemics have done. There is a lot more technology and international cooperation around; governments have more experience dealing with such matters; and a lot has been learnt from China, South Korea and Singapore about the importance of early containment and social distancing. Provided that countries, take the right steps, the number of deaths it is likely to be much smaller than the three major influenza pandemics of the past century – the Spanish Flu in 1918–1919 (20–50 million deaths); the Asian Flu in 1957-58 and the Hong Kong Flu in 1968 (1–4 million deaths each)..

Eventually total deaths could be around the same number as the 2009 “Swine Flu” pandemic which caused between 100,000–400,000 deaths in the first year. But whatever its medical trajectory, people will learn lessons, and adapt, adopt and improve. It is worth looking some of these and what these might mean for Pakistan.

Over the last two decades the thrust for improved efficiency and productivity has driven manufacturing, and many service industries, towards minimizing costs. Two important elements of this have been “just in time delivery” which means firms holding minimum stocks and inventories, and hence lower financing costs; and long supply chains which reduce costs of components. The crisis has brought to the fore the vulnerability of both these processes. With disrupted supply chains and low stocks, many firms in the USA and Europe have found it hard to maintain operations.

The post-COVID world will be obsessed with diversifying risk. Sitting as it does, between China and its biggest markets in Europe and the USA, Pakistan is in a unique position to do two things: first, increase its manufacturing base as an alternate source for industrial components and parts; and second becoming a logistic hub where product inventories can be held and transported to those markets where it is needed. Doing this will not be easy but government and private sector need to work together on this.

Daud Khan works as consultant and advisor for various governments and for international agencies, including the World Bank.

Leila Yasmine Khan is an independent writer and editor based in the Netherlands.

First of all let us look at short term impacts. There is likely to be a sharp drop in domestic consumer demand. Expenditures on food, medical assistance and other essential items would rise but this would be more than offset by lower demand for consumer goods, apparel and services. This drop in demand will be compounded by foreign buyers delaying or cancelling orders; a fall in travel and tourism; and further drops in the stock market which would erode peoples’ wealth and their willingness to spend. There is also likely to be a fall in remittances due to layoffs and delayed salary payments to Pakistani workers in the Middle East and elsewhere.

Lower overall domestic consumer demand will have a negative impact on production and employment. It may be less severe in agriculture where demand for food and other products will remain high, and supplies will continue despite possible local problems related to restrictions on movement of outputs, inputs and labour. The drop may be larger in manufacturing but some companies may try to carry on operating, building up stocks of finished goods, rather than reduce production and lay off staff. The effects are likely to be most severe in the construction and small scale services sector where most of the labour force is hired on a daily wage basis.

On the supply side, there are also likely to be disruptions as there may be shortages of imported raw materials and spare parts. However, one of Pakistan’s key imports is fuel, and prices have dropped sharply. This should help but would require that the positive impact of lower international oil prices works its way quickly through to local consumers.

The severity and duration of the short term demand and supply impacts depends on the measures the government adopts to contain the spread of the virus. So far Sindh has taken the strongest actions. Other provinces and the federal government are also providing guidelines on reducing activities and movements. These measures are not as drastic as in India or some European countries, but would nevertheless have a severe negative impact on the economy. Most likely GDP would fall by more than 1.3 percent estimated by the World Bank and maybe even approach the over 5 percent-10 percent fall projected for several affected countries such as Italy and Spain. Such a fall would cause severe hardship, especially coming on top of a period of high inflation and slow growth. The impact will disproportionately fall on the poorest and weakest sections of the population, such as daily-wage workers and casual labour in activities such as transport, construction, the retail trade, and small hotels and restaurants

But let’s not forget that we Pakistanis are a resistant and strong people. And, in times of crisis, we tend to come together to help each other. This happened at the time of the 2005 earthquake and the 2010 floods when thousands of people volunteered their time, along with billions of PKRs, to help the needy. This time around as well, private citizens, civil society organizations and NGOs, as well as mosque committees and religious groups, are taking on much of the strain of helping the poorest. This includes direct help in cash and food items, continued salaries despite workers’ inability to come to work, and assistance with medical expenses.

However, it is also clear that private support mechanisms will not be able to fully cope. Moreover, such mechanisms tend to be relatively weak in rural areas as the scattered nature of the population makes it difficult to reach effected people. The government is already working to strengthen its social safety nets and in particular the Ehsaas program, the Utility Shops and the newly formed Tiger Force. In rural areas it should also involve police stations, health clinics, agriculture/livestock offices and the network created by the National Rural Support Programmes. All of these must be asked to provide logistic help for both medical assistance and to reach the rural poor with food and income support.

So what can the government do apart from relief related actions? It should use the two major policy instruments at its disposal – the rate of interest and the exchange rate. The State Bank needs to continue to cut interest rates. More importantly, it should require commercial banks to make corresponding decreases in interest rates on outstanding loans to consumers and businesses, and allow them to reschedule repayments. In order to facilitate increased liquidity, commercial banks should be allowed to reduce their statutory liquid reserves and deposits with SBP. At the same time, government should avoid efforts to bolster foreign exchange markets. In fact a slide in the PKR would help Pakistani exporters become more competitive in the face of falling global demand.

Government should also be proactive on calling on various development partners, particularly those with expertise in medical matters, food and nutrition security and social protection, to help design quick impact projects to cushion the poorest. It is worth mentioning that the Government is already accessing some of the funds set aside for the COVID-19 crisis by international agencies such as the World Bank (US$12 billion), the Asian Development Bank (US$6.5 billion) and the IMF (US$50bllion). A special role should be given to the World Food Programme which has much needed expertise in dealing with the crisis logistics, as well as in raising resources. The government should also continue its negotiations with creditors to write off debts or at least delay some of the debt service payments which amount to around 5% of GDP.

In addition, the government should try and take advantage of the price war among oil exporters, and the resulting lower prices. As mentioned above, these cuts should be passed on to consumers, particularly industrial and commercial users, through lower prices for fuel and electricity. There should also be cuts in diesel prices to help agriculture, industry and transporters.

As we move ahead, we need to keep in mind that this outbreak will run its course as other pandemics have done. There is a lot more technology and international cooperation around; governments have more experience dealing with such matters; and a lot has been learnt from China, South Korea and Singapore about the importance of early containment and social distancing. Provided that countries, take the right steps, the number of deaths it is likely to be much smaller than the three major influenza pandemics of the past century – the Spanish Flu in 1918–1919 (20–50 million deaths); the Asian Flu in 1957-58 and the Hong Kong Flu in 1968 (1–4 million deaths each)..

Eventually total deaths could be around the same number as the 2009 “Swine Flu” pandemic which caused between 100,000–400,000 deaths in the first year. But whatever its medical trajectory, people will learn lessons, and adapt, adopt and improve. It is worth looking some of these and what these might mean for Pakistan.

Over the last two decades the thrust for improved efficiency and productivity has driven manufacturing, and many service industries, towards minimizing costs. Two important elements of this have been “just in time delivery” which means firms holding minimum stocks and inventories, and hence lower financing costs; and long supply chains which reduce costs of components. The crisis has brought to the fore the vulnerability of both these processes. With disrupted supply chains and low stocks, many firms in the USA and Europe have found it hard to maintain operations.

The post-COVID world will be obsessed with diversifying risk. Sitting as it does, between China and its biggest markets in Europe and the USA, Pakistan is in a unique position to do two things: first, increase its manufacturing base as an alternate source for industrial components and parts; and second becoming a logistic hub where product inventories can be held and transported to those markets where it is needed. Doing this will not be easy but government and private sector need to work together on this.

Daud Khan works as consultant and advisor for various governments and for international agencies, including the World Bank.

Leila Yasmine Khan is an independent writer and editor based in the Netherlands.