Imran Khan’s first few days in office have triggered both hope and despair. Desperate hope that he means what he says and will prove it by definite actions. Despair because the dubious means he has chosen are at serious odds with the noble ends he has pledged.

His first formal “address to the nation” was not formal at all. He spoke from handwritten notes and reached out directly to the people. This is the method of all populist leaders. It denotes sincerity of purpose and righteousness. He also touched on a to-do list of relevant issues.

The naysayers can rightly point to some embarrassing omissions: missing persons, minority and women’s rights, religious extremism, etc. We must also admit that repeating manifesto pledges isn’t terribly inspiring because he didn’t explain how he intends to go about doing business.

Khan’s supporters say that for now he should be assessed only on the team he has assembled to deliver his reform agenda. They admit to an astounding number of cabinet members and advisors who have “served” the country before, many during the regime of the military dictator General Pervez Musharraf. What’s the fuss about, they ask, if these men and women are all educated, good, competent, qualified and honest? So what if these same people didn’t amount to much in their previous official incarnations? General Musharraf’s reform agenda, they say, was dogged by questions of legitimacy. Imran Khan’s isn’t, they claim. Then there’s the question of the political compromises General Musharraf made when he opted for the political “lotas” of his time to stick to power. But that didn’t undermine reform, they argue, because these people didn’t really wield power. So who did?

The unaccountable bureaucracy, or babus, at every tier of government, we are advised, are the root of all evil. They are wedded to the privileged status quo. They will have to be uprooted if any reform agenda is to be pursued. How to do this is the million-dollar question. Unfortunately, this is easier said than done. Not many answers are blowing in the wind. If the educated, good, honest, competent ministers of past eras failed to uproot the evil bureaucracies that served them faithfully, how is the same lot going to fare now? Didn’t General Musharraf inspire the same sort of hope when he kicked off, among the same sort of people that Imran Khan now does? Didn’t General Musharraf have the support of the other institutions of the state like the judiciary and media that Imran Khan has today?

Alas. If the road to hell is paved with good intentions, sometimes we may legitimately question these as well. How on earth is someone like Sheikh Rashid expected to reform the Railways? How is Asad Umar going to fix the white elephants in the economy if not by enduring the pain of privatization? How is the “corrupt” FBR going to reform the tax system? Who is going to reform the FBR? And how? And so on. So many questions. Such few answers.

To be sure, Dr Ishrat Hussain’s wealth of knowledge about necessary administrative reforms is welcome. But where is the hard-nosed, dedicated, informed team that is going to wade into this cesspool of compromise and cleanse it?

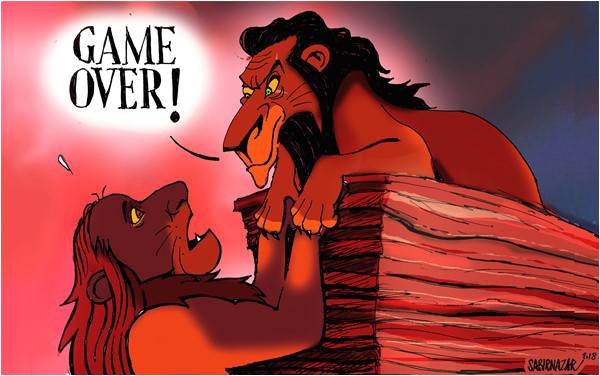

The question of legitimacy is also not to be scoffed at. If the wild allegations of rigging in 2013 were subsequently dismissed by a judicial commission of Imran Khan’s approval, we should not expect the same results this time round. The crude unfairness of the political engineering that has brought Imran Khan to power has come to be deeply embedded in the popular imagination because of several unprecedented but now well established factors. Indeed, it is the political frailty of the end-result – whether in the quality of the elected leaders (more appropriately “puppets”) or the parliamentary numbers in Lahore and Islamabad – that is likely to stall radical reform. By its very nature, this dispensation is built on a historic “compromise” between governments and oppositions, between the military and civilians, and between the different organs of the state like the judiciary and media. The problem with these multiple compromises is their lack of stability. They are all held at gunpoint rather than any willing social-contract consensus. This will work in the short term but cannot endure, like we learnt from our previous experiences under three gunpoint regimes.

For many folks, Imran Khan is genuinely inspirational. For others, if only by contrast with the abysmal lots that have come and gone. But that’s just the beginning of the story. A lot of showy accountability will doubtless assuage the thirst of the masses for some time, as it did in the gunpoint regimes of the 60s, 70s, 80s and 2000s. But all Pied Piper regimes eventually fall into the abyss.

While blind optimism can be dangerously misplaced, it’s only fair to give a new regime time to settle down before taking stock of its performance.

His first formal “address to the nation” was not formal at all. He spoke from handwritten notes and reached out directly to the people. This is the method of all populist leaders. It denotes sincerity of purpose and righteousness. He also touched on a to-do list of relevant issues.

The naysayers can rightly point to some embarrassing omissions: missing persons, minority and women’s rights, religious extremism, etc. We must also admit that repeating manifesto pledges isn’t terribly inspiring because he didn’t explain how he intends to go about doing business.

Khan’s supporters say that for now he should be assessed only on the team he has assembled to deliver his reform agenda. They admit to an astounding number of cabinet members and advisors who have “served” the country before, many during the regime of the military dictator General Pervez Musharraf. What’s the fuss about, they ask, if these men and women are all educated, good, competent, qualified and honest? So what if these same people didn’t amount to much in their previous official incarnations? General Musharraf’s reform agenda, they say, was dogged by questions of legitimacy. Imran Khan’s isn’t, they claim. Then there’s the question of the political compromises General Musharraf made when he opted for the political “lotas” of his time to stick to power. But that didn’t undermine reform, they argue, because these people didn’t really wield power. So who did?

The unaccountable bureaucracy, or babus, at every tier of government, we are advised, are the root of all evil. They are wedded to the privileged status quo. They will have to be uprooted if any reform agenda is to be pursued. How to do this is the million-dollar question. Unfortunately, this is easier said than done. Not many answers are blowing in the wind. If the educated, good, honest, competent ministers of past eras failed to uproot the evil bureaucracies that served them faithfully, how is the same lot going to fare now? Didn’t General Musharraf inspire the same sort of hope when he kicked off, among the same sort of people that Imran Khan now does? Didn’t General Musharraf have the support of the other institutions of the state like the judiciary and media that Imran Khan has today?

Alas. If the road to hell is paved with good intentions, sometimes we may legitimately question these as well. How on earth is someone like Sheikh Rashid expected to reform the Railways? How is Asad Umar going to fix the white elephants in the economy if not by enduring the pain of privatization? How is the “corrupt” FBR going to reform the tax system? Who is going to reform the FBR? And how? And so on. So many questions. Such few answers.

To be sure, Dr Ishrat Hussain’s wealth of knowledge about necessary administrative reforms is welcome. But where is the hard-nosed, dedicated, informed team that is going to wade into this cesspool of compromise and cleanse it?

The question of legitimacy is also not to be scoffed at. If the wild allegations of rigging in 2013 were subsequently dismissed by a judicial commission of Imran Khan’s approval, we should not expect the same results this time round. The crude unfairness of the political engineering that has brought Imran Khan to power has come to be deeply embedded in the popular imagination because of several unprecedented but now well established factors. Indeed, it is the political frailty of the end-result – whether in the quality of the elected leaders (more appropriately “puppets”) or the parliamentary numbers in Lahore and Islamabad – that is likely to stall radical reform. By its very nature, this dispensation is built on a historic “compromise” between governments and oppositions, between the military and civilians, and between the different organs of the state like the judiciary and media. The problem with these multiple compromises is their lack of stability. They are all held at gunpoint rather than any willing social-contract consensus. This will work in the short term but cannot endure, like we learnt from our previous experiences under three gunpoint regimes.

For many folks, Imran Khan is genuinely inspirational. For others, if only by contrast with the abysmal lots that have come and gone. But that’s just the beginning of the story. A lot of showy accountability will doubtless assuage the thirst of the masses for some time, as it did in the gunpoint regimes of the 60s, 70s, 80s and 2000s. But all Pied Piper regimes eventually fall into the abyss.

While blind optimism can be dangerously misplaced, it’s only fair to give a new regime time to settle down before taking stock of its performance.