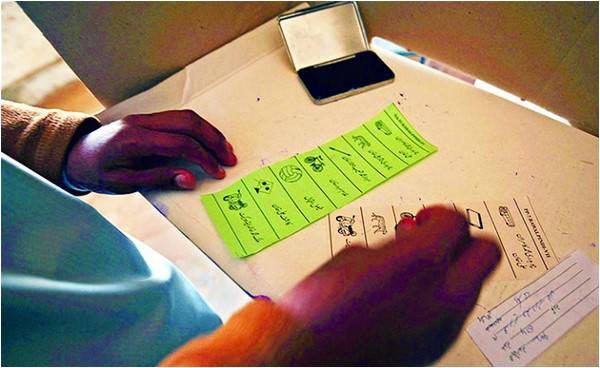

On July 25, 2018, in my village, a group of enthusiastic young boys set up camp outside a polling station in Memon Mohalla, Khairpur Mirs, Sindh. With laptops and battery packs ready, they beamed with pride, asking all those who stopped by to inspect their computerised lists and digital preparedness. Inside, the polling station was empty for much of the afternoon. Tech-savvy young boys messaged everyone. But perhaps not everyone could read or charge phones or figure out which new polling station to go to. With good intentions or bad, new methods and those not new at all, Pakistan’s elections came to pass.

Through it all, we heard a lot about election engineering. Electioneering itself is an old verb. Etymological sources suggest that it has existed in the English Language much longer than the verb ‘engineering.’ Electioneering generally refers to working for the success of a political party or candidate. Its practice is almost as old as democracy itself.

In recent years, electoral engineering emerged in the literature as a means for introducing meaningful electoral reform. In Pakistan however, the term carries a different, more pejorative connotation. Critics insist that 2018 election results were engineered. While I can’t determine with precision whether they were engineered, I examine whether Pakistan’s democracy will meaningfully survive elections tainted with apparent unfairness. Towards that end, I explore the pre-poll process, polling day irregularities and post-poll outlook.

Elections Act of 2017

The story of Elections 2018 begins with systemic reform. In a bid to improve the elections’ process, the outgoing Parliament passed the Elections Act of 2017 (Act). Mainly, the Act increased powers of the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP), introduced measures supporting women’s right to vote, improved citizens access to complaint procedures and laid out principles for the delimitation process.

Delimitation

Delimitation - the idea and the process - aims to give each voter the same right to vote and make an impact. When populations in electoral districts vary widely, a vote in a more populous constituency counts for less than a vote in a less populated constituency. Delimitation, in principle, can reduce inequality in voting power.

Article 51(5) of Pakistan’s Constitution provides for delimitation. The Elections Act of 2017 sets out procedures and principles. The Act sets 10 percent as the limit for variation in the size of constituencies for an assembly or local government position. It also permits some deviation from the 10 percent limit with well articulated reasons.

The 10 percent limitation falls in line with international best practice. In the U.S. for instance, when states create congressional districts, the districts must have the same population. For state and local elections, the populations of electoral districts must be roughly equal, with any variation not exceeding a few percentage points. In theory, this ensures that ‘one person, one vote’ means just that. Through roughly equal constituencies or electoral districts, voting in one constituency carries the same weight as voting in any other.

The next issue concerns data for drawing up constituencies. Ideally, districts or constituencies should be delimited based on the voting population. But many countries, including the US, permit delimitation based on total population data. In Pakistan, the Constitution provides for delimitation based on official census data. Since official census results were not available before the elections, Parliament passed the 24th Amendment to the Constitution, enabling the ECP to consider provisional census data for delimitation purposes.

Since 1977, most of Pakistan’s delimitation exercises have been discretionary, military-led and largely ungrounded in principle. Through the Elections Act of 2017, Parliament articulated clear principles and methods for delimitation. For the first time, delimitation appeared to be based on principles.

But appearances can be deceiving. With delimitation came clashes with the requirement that no constituency cross district boundaries. In general, overlapping electoral and district boundaries ensure good governance. Strictly complying with the 10 percent rule would have required redrawing district boundaries. Given time constraints, the delimitation process continued in violation of the 10 percent limit in some parts of the country.

Consequently, voting in one constituency counted for more or less than voting in other constituencies. All constituencies were equal but some constituencies were more equal than others.

Punjab, de-limited

Allegations of gerrymandering accompanied delimitation measures. Gerrymandering involves altering boundaries of electoral districts or constituencies to favour one political party or candidate over the other. These allegations were most pronounced in the Punjab and Sindh.

Delimitation jolted the Punjab, affecting nearly 21 of 35 electoral districts. Areas in central and north Punjab - strongholds of the PML-N - were specifically affected.

Eleven districts of north and central Punjab lost one National Assembly seat each. Of those 11 seats, other provinces gained seven seats, south Punjab gained three seats and Lahore got an additional seat. For provincial assembly seats, five districts in north and central Punjab lost one provincial assembly seat each. In retrospect, this seat adjustment helps explain the reduced impact of PML-N’s performance in north and central Punjab.

Some effects of de-limitation, anticipated or not, caused much confusion. To illustrate: In Gujranwala PP-63, Punjab Assembly’s longest serving member found that his ancestral hometown was no longer part of his electoral constituency.

Other areas

In Sindh, the total number of seats remained unaltered but the ECP allocated seats differently. Since Sindh’s share of districts increased from 16 to 29, the ECP divided the province’s 61 seats across 29 districts instead of 16 districts. Accordingly, districts found their fortunes altered. Out of Sindh’s 29 districts, only Tharparker and Ghotki had the same number of seats as 2013.

With Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s population bulge, the province received four new National Assembly seats. Balochistan gained two National Assembly seats, with Quetta’s seat share considerably increasing.

In all, the ECP received more than 1,285 objections to the delimitations process. It addressed many of them, but it is unclear whether it addressed them all.

Balochistan and the Senate

To follow trends in Pakistani politics, follow Balochistan. Over this past year, changes in Balochistan were predictive of changes seen elsewhere. With the dawn of the new year, Balochistan’s PML-N backed Chief Minister Sanaullah Zehri resigned ahead of an expected no confidence motion. Despite support from National Party President Hasil Bizenjo and Mahmood Achakzai’s Pashtunkhwa Mili Awami Party (PKMAP), Zehri found himself resigning to pre-empt a no-confidence motion tabled by 14 members of the Balochistan Assembly from BNP, ANP, JUI-F, PML-Q and some dissenting PML-N members.

With Zehri out, Abdul Quddus Bizenjo of PML-Q assumed office as chief minister in January 2018. The PML-N failed to nominate a candidate to oppose Bizenjo in his bid for office. The PML-N members voted for Bizenjo, enabling him to win with 41 out of 65 votes in the house.

Oddly, Bizenjo’s other claim to fame is that he won from Awaran, a district of 57,666 registered voters, with 544 votes - the lowest number of votes received by any winning general candidate in Pakistan’s history.

Bizenjo’s win impacted Pakistan’s Senate elections. With 11 senators from Balochistan set to resign and the PML-N absent, Bizenjo could have manoeuvred control over most of Pakistan’s Senate. Instead, Balochistan elected an assortment of independents and others to the Senate. The PML-N failed to secure any Senate seat from Balochistan.

Although the PML-N, with its 46 seats, emerged as the largest party Senate, it was unable to have its nominee elected as chairman. With help from the PPP, the PTI, the MQM and independent senators, Sadiq Sanjrani, a little known independent senator from Balochistan, emerged at the helm as chairman of Pakistan’s Senate.

At around the same time, in March 2018, Bizenjo formed the Balochistan Awami Party (BAP). Dissidents from the PML-N, the PML-Q, the PkMAP and the PTI, among others, joined Balochistan Awami Party (BAP). Within a few months of its creation, the newly-created and little known BAP went on to win the largest number of seats in Balochistan’s newly elected assembly. Along with the PTI, BAP is set to form government in the province.

Akhtar Mengal’s Balochistan National Party emerged as the second largest party in Balochistan’s Assembly. The PML-N went from having 19 seats to securing only. Hasil Bizenjo’s National Party of Pakistan and Mahmood Achakzai’s PkMAP, previously controlling at least 24 seats in Balochistan’s Assembly, appear to have lost everywhere in the province.

Mercurial political fortunes in Balochistan rise and fall. Fair appears foul and foul appears fair. Such is our chaos.

Pre-Poll Violence

Political violence in Pakistan tends to rise in the run up to elections. In 2008, over 150 people died and 400 people were injured in electoral violence. In 2013, 146 terrorist attacks took place between January 2013 and the elections in May 2013. Targets included party workers, election officers and polling stations.

In this year’s elections, the violence persisted. On July 13, the blast in Mastung claimed the lives of 128 people, including that of Mir Siraj Raisani, the BAP candidate from Mastung. On the same day, a blast in Bannu killed five people and wounded 37 others, in an attempt to assassinate former Khyber Pakhtunkhwa chief minister Akram Durrani. Previously, on July 11, ANP’s Haroon Bilour and 13 others died when a bomber targeted ANP’s rally. On July 22, PTI candidate Ikramullah Gandapur and his driver were killed in a bomb blast. Two days later, assailants attacked and killed three soldiers escorting polling agents in Dashtuk, Balochistan. In Khairpur Mirs, Sindh, clashes between the Grand Democratic Alliance (GDA) and PPP resulted in the death of a young boy.

On election day in 2018, a bomb blast near a polling station in Quetta claimed 31 lives. In Larkana, Sindh, three people were injured in a grenade attack on a PPP camp. In Swabi, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, a gun fight between the PTI and ANP resulted in the death of a polling agent. In Nasirabad, two activists were injured in the exchange of gunfire. Skirmishes between the GDA and PPP left several people injured in Sindh.

Overall, even though the run-up to the 2018 elections was violent, the violence was different. In 2013, the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) explicitly targeted liberal parties such as the ANP, PPP and MQM. This time, the violence was more diffuse, largely grounded in local politics and perhaps more senseless.

Sharifs arrested

In July 2017, Pakistan’s Supreme Court removed Nawaz Sharif from office, finding that Sharif had not declared among his assets, an un-received ‘receivable’ salary from his son’s company Capital FZE. The court’s conception of receivables and assets caused a stir in Pakistan’s legal circles, creating controversy over dictionary definitions and meanings.

In line with the Supreme Court’s orders, the Sharifs faced proceedings in National Accountability Bureau (NAB) courts. On July 6, 2018, about three weeks before the 2018 elections, the NAB court found Nawaz Sharif guilty of owning unexplained assets. In his judgement, Justice Basheer observed that “it is difficult to establish ownership of (Avenfield) properties since they were purchased through offshore companies in tax haven jurisdictions.” With that acknowledged, the court used circumstantial evidence to presume that Sharif was the beneficial owner of those properties, shifted the burden of proof to Sharif and convicted him since he was unable to prove how he purchased Avenfield flats.

In general, world over, courts tend to presume that the accused is innocent till proven guilty. The prosecution must establish its case beyond reasonable doubt and the accused can defend himself without so much as saying a word. But in Pakistan, it appears that the National Accountability Ordinance permits otherwise.

The NAB court convicted Nawaz Sharif, sentencing him to 10 years imprisonment and imposing a fine of 8 million pounds. Sharif’s daughter, Maryam Nawaz, was convicted of abetment, receiving a sentence of 7 years imprisonment and a fine of 2 million pounds. Maryam Nawaz’s husband, Safdar Nawaz, was also convicted and sentenced to imprisonment for one year. The court deemed Nawaz’s sons, Hussain and Hassan Nawaz, proclaimed offenders and ordered non-bailable arrest warrants for them.

When the court announced its judgment, the Sharifs were in London, where Nawaz’s wife, Kulsoom Nawaz, is undergoing treatment. Against political expectations to the contrary, the Sharifs returned on Friday the 13th. Before their arrival, Lahore was under lockdown. It was unclear whether the PML-N managed to gather a sizeable crowd for their welcome. Without much fanfare, uniformed officers arrested Nawaz Sharif and Maryam Nawaz from their plane.

In the pre-poll phase, the Sharif family found itself at the centre of much drama: Sharif’s mother released statements, television cameras swarmed around Kulsoom Nawaz’s hospital bed and Junaid Safdar faced assault charges over his clashing with a protester outside the Avenfield Properties in London. But it appears that the Sharifs’ return to Pakistan failed to generate a sympathy vote big enough to substantially alter the PML-N’s political fortune.

The Sharifs were not arrested alone. The interim government took to arresting over three hundred PML-N members before Nawaz Sharif’s arrival. Many PML-N leaders were also charged with terrorism after protestors clashed with the police on the day of Sharif’s return.

Among other curiously timed arrests, Hanif Abbasi’s arrest three days before elections, seemed significantly out of line with routine practice.

Media Watch

In line with Pakistan’s general disposition towards censorship, news media channels and newspapers found their freedom of speech circumscribed. Channels such as Geo TV were shut in parts of Pakistan. The circulation of Dawn newspapers was stopped in some parts of the country. Many prominent op-ed writers took to social media to display their write-ups since newspapers could no longer publish their articles.

With selective media silencing came other instruments of propaganda. As TV anchorpersons displayed favouritism, the PML-N members defected, courts pronounced judgments against the Sharifs and pro-Sharif voices found themselves silenced. The stage for PTI’s imminent win was set. Activists of all political parties interviewed for this piece confirm the role the media shaping played in the elections.

Election Day

Elections in Pakistan never are free of chaos. People die, names are deleted from electoral lists, polling stations change at the last minute and agents don’t show up on time or at all.

Reports generally indicate that the events of the hours of polling, between 9am and 5pm, proceeded as usual. Barring violence and complaints of missing lists and names, most sources interviewed for this piece - hailing variously from Karachi, rural Sindh, rural Punjab, Lahore and KPK- thought that the polling process itself did not deviated significantly from the usual chaotic business of elections.

Despite the rain and heat in various parts of the country, women voted in record numbers, particularly in areas around Upper and Lower Dir, where it is uncommon for women to vote.

In areas such as Gujranwala, complaints made to the ECP indicate that polling stations were shut down for over an hour for unexplained reasons. In Murree, a political activist who did not wish to be named explained that a new polling station opened in his area the night before the election, causing considerable confusion, delay and difficulty.

Sources from rural Sindh claimed that government staff intentionally slowed down polling in some women’s polling stations in their districts. In Karachi, complaints emerging from Lyari suggest that Bilawal Bhutto Zardari’s election agent was unlawfully denied entry to polling stations.

Post-poll confusion

Most complaints emerged after polling ended. For the most part, they concerned presiding officers’ unlawfully refusing to give Form 45, excluding polling agents and generally refusing to share results.

Form 45 is a necessary part of the result sharing process. In every election, without fail and usually within a few hours, polling agents receive an official form with the count of votes for each candidate. This form allows candidates to contest any discrepancy in the final count and generally promotes transparency.

For the first time in Pakistan’s electoral history, many candidates, hailing from different political parties and regions, confirmed that they did not receive Form 45 results on election day. In Karachi, Jibran Nasir and his team took to Twitter to protest the denial of Form 45 on election day.

Eight days after the elections, the PPP claimed that it was still waiting for Form 45 vote counts from over 200 polling stations in Lyari. The PPP sources further allege that around 250 of their polling agents were wrongly excluded from the vote counting process. In the Punjab, the PML-N politicians from Dera Ghazi Khan, Lahore, Murree, Gujranwala and Toba Tek Singh, among other areas, claim that they did not receive Form 45 counts on election day.

In Khairpur, campaign agents waited outside polling stations until 6am the next day, in hope of Form 45 vote counts, which they were denied in some cases. Official results were delayed by at least a day for some seats.

When asked, presiding officers squarely laid the blame at the door of the new Results Transmission Software (RTS). They claimed that they were inadequately trained to use the software.

A few days before the elections, some Returning Officers (ROs) in the Punjab reportedly wrote to National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA), pointing out the dangers of experimenting with new software on election day. Protesting ROs noted that the software was likely to fail, the ECP had no back-up in place and election staff were inadequately trained. The ECP alleges that the software stopped working a few hours after the close of polling, when the majority of results started coming through. In some cases, inexperienced presiding officers struggled with the new app-based software. In many cases, the backup computer link system did not work. Eventually, some results were faxed to the ECP in the early hours of the morning.

Technological failures notwithstanding, political parties and their activists suggest foul play. For its part, the ECP denies allegations and passes the buck to NADRA, claiming that NADRA designed flawed software.

Flawed software or not: delays in revealing results, denying official Form 45 vote counts and excluding some political agents from the counting process created apparent unfairness. Throughout Pakistan’s electoral history, candidates have received results on the same day. To some, results delayed were results denied - quite literally.

Recounts

Over the last few days, vote recounts became controversial. In general, a presiding officer may call for a recount once on his own initiative or at the request of a candidate. A RO may order a recount when a candidate or his agent submits a written request and the margin of victory is less than five percent of votes polled or 10,000 votes, whichever is lesser.

The PML-N activists interviewed for this article expressed concerns over vote recounts. They pointed to this contrast: PML-N’s Shehbaz Sharif lost by a margin of 718 votes in Karachi’s NA-249. The RO denied his plea for a recount. At the same time, in NA-129 Lahore, PTI’s Aleem Khan, who lost with a margin of over 8,000 votes to the PML-N’s Ayaz Sadiq, managed to secure a recount. When the RO found that Sadiq’s tally was increasing as a consequence of the recount, the RO discontinued the process.

By far, the most intriguing vote recounting scene played out in former prime minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi’s district, NA-57 Murree. Videos show a tense situation developing between soldiers and the PML-N supporters outside a local court, where supporters reportedly resisted attempts to deny a recount. Eventually, the ECP ordered a recount and the tense situation abated.

Winners, losers and winners

Even with delays, denials and much confusion, the 2018 elections give some cause to celebrate. In Upper and Lower Dir, where women’s votes were previously disallowed, several women voted. All parties fielded at least five percent women on general seats. PTI’s Ghulam Bibi Bharwana and Zartaj Gul succeeded in areas where women do not usually win. PTI’s Yasmin Rashid also successfully secured a provincial seat and appeared in the running for the post of Punjab’s chief minister.

PPP’s strong women - Azra Pechuho, Faryal Talpur, Nafisa Shah, Shazia Marri - won their seats with comfortable margins.

What next?

A PTI-led government is now in the Parliament. Here, it is important to explore key political issues likely to shape the path ahead. There are three things to watch for: PTI’s coalition-building skills, its management of excluded politicians and capacity to deliver on promises.

Despite Imran Khan’s victory in five federal constituencies, his party failed to secure a majority in the National Assembly. This is something of a first for Pakistan. No other leader of a major political party has succeeded in securing wins from several federal constituencies while failing to ensure a majority win for his party. Imran Khan’s personal brand appears stronger than that of his party. It remains open to question whether Pakistan’s former cricket captain is ready for the task of coalition building and leading from behind.

For its part, the PML-N faces an existential crisis. Although its overall vote count reduced significantly, it retained some presence along its traditional stronghold around the Grand Trunk Road. As the former blue-eyed child of Pakistan’s establishment, the PML-N is a relative stranger to the politics of opposition and dissent. Although General Musharraf’s coup d’etat led to the ouster of Nawaz Sharif’s government in 1999, Sharif did not engage in much by way of dissent. He traded jail for Saudi Arabia and many of his party members defected to form the PML-Q. Several defectors returned to the PML-N after Nawaz Sharif’s return to Pakistan in 2007. For the most part, PML-N’s rank and file has enjoyed support from the army and held positions in government. Whether the PML-N members have the appetite and aptitude for opposition politics remains to be seen. From the ethnic lens, for the first time in Pakistan’s history, a mainstream Punjabi leader is standing up against the Establishment. But the overall impact of Sharif’s stance remains ambiguous.

In a curious turn of events, the old guard of Pakhtoon politics remains outside Parliament: Maulana Fazlur Rehman of JUI-F, Asfandiyar Wali of ANP, Siraj-ul-Haq of JI, Mahmood Achakzai (PkMAP) and others apparently failed to win their seats. Managing their absence from the halls of Parliament may prove difficult. A retired militaryman, who did not wish to be named, remarked, “Imran Khan calls Fazlur Rehman ‘Maulana Diesel’. Does Imran not realize that diesel is highly flammable?”

Through it all, we heard a lot about election engineering. Electioneering itself is an old verb. Etymological sources suggest that it has existed in the English Language much longer than the verb ‘engineering.’ Electioneering generally refers to working for the success of a political party or candidate. Its practice is almost as old as democracy itself.

In recent years, electoral engineering emerged in the literature as a means for introducing meaningful electoral reform. In Pakistan however, the term carries a different, more pejorative connotation. Critics insist that 2018 election results were engineered. While I can’t determine with precision whether they were engineered, I examine whether Pakistan’s democracy will meaningfully survive elections tainted with apparent unfairness. Towards that end, I explore the pre-poll process, polling day irregularities and post-poll outlook.

Elections Act of 2017

The story of Elections 2018 begins with systemic reform. In a bid to improve the elections’ process, the outgoing Parliament passed the Elections Act of 2017 (Act). Mainly, the Act increased powers of the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP), introduced measures supporting women’s right to vote, improved citizens access to complaint procedures and laid out principles for the delimitation process.

Delimitation

Delimitation - the idea and the process - aims to give each voter the same right to vote and make an impact. When populations in electoral districts vary widely, a vote in a more populous constituency counts for less than a vote in a less populated constituency. Delimitation, in principle, can reduce inequality in voting power.

Article 51(5) of Pakistan’s Constitution provides for delimitation. The Elections Act of 2017 sets out procedures and principles. The Act sets 10 percent as the limit for variation in the size of constituencies for an assembly or local government position. It also permits some deviation from the 10 percent limit with well articulated reasons.

The 10 percent limitation falls in line with international best practice. In the U.S. for instance, when states create congressional districts, the districts must have the same population. For state and local elections, the populations of electoral districts must be roughly equal, with any variation not exceeding a few percentage points. In theory, this ensures that ‘one person, one vote’ means just that. Through roughly equal constituencies or electoral districts, voting in one constituency carries the same weight as voting in any other.

The next issue concerns data for drawing up constituencies. Ideally, districts or constituencies should be delimited based on the voting population. But many countries, including the US, permit delimitation based on total population data. In Pakistan, the Constitution provides for delimitation based on official census data. Since official census results were not available before the elections, Parliament passed the 24th Amendment to the Constitution, enabling the ECP to consider provisional census data for delimitation purposes.

Since 1977, most of Pakistan’s delimitation exercises have been discretionary, military-led and largely ungrounded in principle. Through the Elections Act of 2017, Parliament articulated clear principles and methods for delimitation. For the first time, delimitation appeared to be based on principles.

But appearances can be deceiving. With delimitation came clashes with the requirement that no constituency cross district boundaries. In general, overlapping electoral and district boundaries ensure good governance. Strictly complying with the 10 percent rule would have required redrawing district boundaries. Given time constraints, the delimitation process continued in violation of the 10 percent limit in some parts of the country.

Consequently, voting in one constituency counted for more or less than voting in other constituencies. All constituencies were equal but some constituencies were more equal than others.

Despite the rain and heat in various parts of the country, women voted in record numbers, particularly in areas around Upper and Lower Dir, where it is uncommon for women to vote

Punjab, de-limited

Allegations of gerrymandering accompanied delimitation measures. Gerrymandering involves altering boundaries of electoral districts or constituencies to favour one political party or candidate over the other. These allegations were most pronounced in the Punjab and Sindh.

Delimitation jolted the Punjab, affecting nearly 21 of 35 electoral districts. Areas in central and north Punjab - strongholds of the PML-N - were specifically affected.

Eleven districts of north and central Punjab lost one National Assembly seat each. Of those 11 seats, other provinces gained seven seats, south Punjab gained three seats and Lahore got an additional seat. For provincial assembly seats, five districts in north and central Punjab lost one provincial assembly seat each. In retrospect, this seat adjustment helps explain the reduced impact of PML-N’s performance in north and central Punjab.

Some effects of de-limitation, anticipated or not, caused much confusion. To illustrate: In Gujranwala PP-63, Punjab Assembly’s longest serving member found that his ancestral hometown was no longer part of his electoral constituency.

Other areas

In Sindh, the total number of seats remained unaltered but the ECP allocated seats differently. Since Sindh’s share of districts increased from 16 to 29, the ECP divided the province’s 61 seats across 29 districts instead of 16 districts. Accordingly, districts found their fortunes altered. Out of Sindh’s 29 districts, only Tharparker and Ghotki had the same number of seats as 2013.

With Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s population bulge, the province received four new National Assembly seats. Balochistan gained two National Assembly seats, with Quetta’s seat share considerably increasing.

In all, the ECP received more than 1,285 objections to the delimitations process. It addressed many of them, but it is unclear whether it addressed them all.

Balochistan and the Senate

To follow trends in Pakistani politics, follow Balochistan. Over this past year, changes in Balochistan were predictive of changes seen elsewhere. With the dawn of the new year, Balochistan’s PML-N backed Chief Minister Sanaullah Zehri resigned ahead of an expected no confidence motion. Despite support from National Party President Hasil Bizenjo and Mahmood Achakzai’s Pashtunkhwa Mili Awami Party (PKMAP), Zehri found himself resigning to pre-empt a no-confidence motion tabled by 14 members of the Balochistan Assembly from BNP, ANP, JUI-F, PML-Q and some dissenting PML-N members.

With Zehri out, Abdul Quddus Bizenjo of PML-Q assumed office as chief minister in January 2018. The PML-N failed to nominate a candidate to oppose Bizenjo in his bid for office. The PML-N members voted for Bizenjo, enabling him to win with 41 out of 65 votes in the house.

Oddly, Bizenjo’s other claim to fame is that he won from Awaran, a district of 57,666 registered voters, with 544 votes - the lowest number of votes received by any winning general candidate in Pakistan’s history.

Bizenjo’s win impacted Pakistan’s Senate elections. With 11 senators from Balochistan set to resign and the PML-N absent, Bizenjo could have manoeuvred control over most of Pakistan’s Senate. Instead, Balochistan elected an assortment of independents and others to the Senate. The PML-N failed to secure any Senate seat from Balochistan.

Although the PML-N, with its 46 seats, emerged as the largest party Senate, it was unable to have its nominee elected as chairman. With help from the PPP, the PTI, the MQM and independent senators, Sadiq Sanjrani, a little known independent senator from Balochistan, emerged at the helm as chairman of Pakistan’s Senate.

At around the same time, in March 2018, Bizenjo formed the Balochistan Awami Party (BAP). Dissidents from the PML-N, the PML-Q, the PkMAP and the PTI, among others, joined Balochistan Awami Party (BAP). Within a few months of its creation, the newly-created and little known BAP went on to win the largest number of seats in Balochistan’s newly elected assembly. Along with the PTI, BAP is set to form government in the province.

Akhtar Mengal’s Balochistan National Party emerged as the second largest party in Balochistan’s Assembly. The PML-N went from having 19 seats to securing only. Hasil Bizenjo’s National Party of Pakistan and Mahmood Achakzai’s PkMAP, previously controlling at least 24 seats in Balochistan’s Assembly, appear to have lost everywhere in the province.

Mercurial political fortunes in Balochistan rise and fall. Fair appears foul and foul appears fair. Such is our chaos.

Pre-Poll Violence

Political violence in Pakistan tends to rise in the run up to elections. In 2008, over 150 people died and 400 people were injured in electoral violence. In 2013, 146 terrorist attacks took place between January 2013 and the elections in May 2013. Targets included party workers, election officers and polling stations.

In this year’s elections, the violence persisted. On July 13, the blast in Mastung claimed the lives of 128 people, including that of Mir Siraj Raisani, the BAP candidate from Mastung. On the same day, a blast in Bannu killed five people and wounded 37 others, in an attempt to assassinate former Khyber Pakhtunkhwa chief minister Akram Durrani. Previously, on July 11, ANP’s Haroon Bilour and 13 others died when a bomber targeted ANP’s rally. On July 22, PTI candidate Ikramullah Gandapur and his driver were killed in a bomb blast. Two days later, assailants attacked and killed three soldiers escorting polling agents in Dashtuk, Balochistan. In Khairpur Mirs, Sindh, clashes between the Grand Democratic Alliance (GDA) and PPP resulted in the death of a young boy.

On election day in 2018, a bomb blast near a polling station in Quetta claimed 31 lives. In Larkana, Sindh, three people were injured in a grenade attack on a PPP camp. In Swabi, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, a gun fight between the PTI and ANP resulted in the death of a polling agent. In Nasirabad, two activists were injured in the exchange of gunfire. Skirmishes between the GDA and PPP left several people injured in Sindh.

Overall, even though the run-up to the 2018 elections was violent, the violence was different. In 2013, the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) explicitly targeted liberal parties such as the ANP, PPP and MQM. This time, the violence was more diffuse, largely grounded in local politics and perhaps more senseless.

Sharifs arrested

In July 2017, Pakistan’s Supreme Court removed Nawaz Sharif from office, finding that Sharif had not declared among his assets, an un-received ‘receivable’ salary from his son’s company Capital FZE. The court’s conception of receivables and assets caused a stir in Pakistan’s legal circles, creating controversy over dictionary definitions and meanings.

In line with the Supreme Court’s orders, the Sharifs faced proceedings in National Accountability Bureau (NAB) courts. On July 6, 2018, about three weeks before the 2018 elections, the NAB court found Nawaz Sharif guilty of owning unexplained assets. In his judgement, Justice Basheer observed that “it is difficult to establish ownership of (Avenfield) properties since they were purchased through offshore companies in tax haven jurisdictions.” With that acknowledged, the court used circumstantial evidence to presume that Sharif was the beneficial owner of those properties, shifted the burden of proof to Sharif and convicted him since he was unable to prove how he purchased Avenfield flats.

In general, world over, courts tend to presume that the accused is innocent till proven guilty. The prosecution must establish its case beyond reasonable doubt and the accused can defend himself without so much as saying a word. But in Pakistan, it appears that the National Accountability Ordinance permits otherwise.

The NAB court convicted Nawaz Sharif, sentencing him to 10 years imprisonment and imposing a fine of 8 million pounds. Sharif’s daughter, Maryam Nawaz, was convicted of abetment, receiving a sentence of 7 years imprisonment and a fine of 2 million pounds. Maryam Nawaz’s husband, Safdar Nawaz, was also convicted and sentenced to imprisonment for one year. The court deemed Nawaz’s sons, Hussain and Hassan Nawaz, proclaimed offenders and ordered non-bailable arrest warrants for them.

When the court announced its judgment, the Sharifs were in London, where Nawaz’s wife, Kulsoom Nawaz, is undergoing treatment. Against political expectations to the contrary, the Sharifs returned on Friday the 13th. Before their arrival, Lahore was under lockdown. It was unclear whether the PML-N managed to gather a sizeable crowd for their welcome. Without much fanfare, uniformed officers arrested Nawaz Sharif and Maryam Nawaz from their plane.

In the pre-poll phase, the Sharif family found itself at the centre of much drama: Sharif’s mother released statements, television cameras swarmed around Kulsoom Nawaz’s hospital bed and Junaid Safdar faced assault charges over his clashing with a protester outside the Avenfield Properties in London. But it appears that the Sharifs’ return to Pakistan failed to generate a sympathy vote big enough to substantially alter the PML-N’s political fortune.

The Sharifs were not arrested alone. The interim government took to arresting over three hundred PML-N members before Nawaz Sharif’s arrival. Many PML-N leaders were also charged with terrorism after protestors clashed with the police on the day of Sharif’s return.

Among other curiously timed arrests, Hanif Abbasi’s arrest three days before elections, seemed significantly out of line with routine practice.

Media Watch

In line with Pakistan’s general disposition towards censorship, news media channels and newspapers found their freedom of speech circumscribed. Channels such as Geo TV were shut in parts of Pakistan. The circulation of Dawn newspapers was stopped in some parts of the country. Many prominent op-ed writers took to social media to display their write-ups since newspapers could no longer publish their articles.

With selective media silencing came other instruments of propaganda. As TV anchorpersons displayed favouritism, the PML-N members defected, courts pronounced judgments against the Sharifs and pro-Sharif voices found themselves silenced. The stage for PTI’s imminent win was set. Activists of all political parties interviewed for this piece confirm the role the media shaping played in the elections.

Election Day

Elections in Pakistan never are free of chaos. People die, names are deleted from electoral lists, polling stations change at the last minute and agents don’t show up on time or at all.

Reports generally indicate that the events of the hours of polling, between 9am and 5pm, proceeded as usual. Barring violence and complaints of missing lists and names, most sources interviewed for this piece - hailing variously from Karachi, rural Sindh, rural Punjab, Lahore and KPK- thought that the polling process itself did not deviated significantly from the usual chaotic business of elections.

Despite the rain and heat in various parts of the country, women voted in record numbers, particularly in areas around Upper and Lower Dir, where it is uncommon for women to vote.

In areas such as Gujranwala, complaints made to the ECP indicate that polling stations were shut down for over an hour for unexplained reasons. In Murree, a political activist who did not wish to be named explained that a new polling station opened in his area the night before the election, causing considerable confusion, delay and difficulty.

Sources from rural Sindh claimed that government staff intentionally slowed down polling in some women’s polling stations in their districts. In Karachi, complaints emerging from Lyari suggest that Bilawal Bhutto Zardari’s election agent was unlawfully denied entry to polling stations.

Post-poll confusion

Most complaints emerged after polling ended. For the most part, they concerned presiding officers’ unlawfully refusing to give Form 45, excluding polling agents and generally refusing to share results.

Form 45 is a necessary part of the result sharing process. In every election, without fail and usually within a few hours, polling agents receive an official form with the count of votes for each candidate. This form allows candidates to contest any discrepancy in the final count and generally promotes transparency.

For the first time in Pakistan’s electoral history, many candidates, hailing from different political parties and regions, confirmed that they did not receive Form 45 results on election day. In Karachi, Jibran Nasir and his team took to Twitter to protest the denial of Form 45 on election day.

Eight days after the elections, the PPP claimed that it was still waiting for Form 45 vote counts from over 200 polling stations in Lyari. The PPP sources further allege that around 250 of their polling agents were wrongly excluded from the vote counting process. In the Punjab, the PML-N politicians from Dera Ghazi Khan, Lahore, Murree, Gujranwala and Toba Tek Singh, among other areas, claim that they did not receive Form 45 counts on election day.

In Khairpur, campaign agents waited outside polling stations until 6am the next day, in hope of Form 45 vote counts, which they were denied in some cases. Official results were delayed by at least a day for some seats.

When asked, presiding officers squarely laid the blame at the door of the new Results Transmission Software (RTS). They claimed that they were inadequately trained to use the software.

A few days before the elections, some Returning Officers (ROs) in the Punjab reportedly wrote to National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA), pointing out the dangers of experimenting with new software on election day. Protesting ROs noted that the software was likely to fail, the ECP had no back-up in place and election staff were inadequately trained. The ECP alleges that the software stopped working a few hours after the close of polling, when the majority of results started coming through. In some cases, inexperienced presiding officers struggled with the new app-based software. In many cases, the backup computer link system did not work. Eventually, some results were faxed to the ECP in the early hours of the morning.

Technological failures notwithstanding, political parties and their activists suggest foul play. For its part, the ECP denies allegations and passes the buck to NADRA, claiming that NADRA designed flawed software.

Flawed software or not: delays in revealing results, denying official Form 45 vote counts and excluding some political agents from the counting process created apparent unfairness. Throughout Pakistan’s electoral history, candidates have received results on the same day. To some, results delayed were results denied - quite literally.

Recounts

Over the last few days, vote recounts became controversial. In general, a presiding officer may call for a recount once on his own initiative or at the request of a candidate. A RO may order a recount when a candidate or his agent submits a written request and the margin of victory is less than five percent of votes polled or 10,000 votes, whichever is lesser.

The PML-N activists interviewed for this article expressed concerns over vote recounts. They pointed to this contrast: PML-N’s Shehbaz Sharif lost by a margin of 718 votes in Karachi’s NA-249. The RO denied his plea for a recount. At the same time, in NA-129 Lahore, PTI’s Aleem Khan, who lost with a margin of over 8,000 votes to the PML-N’s Ayaz Sadiq, managed to secure a recount. When the RO found that Sadiq’s tally was increasing as a consequence of the recount, the RO discontinued the process.

By far, the most intriguing vote recounting scene played out in former prime minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi’s district, NA-57 Murree. Videos show a tense situation developing between soldiers and the PML-N supporters outside a local court, where supporters reportedly resisted attempts to deny a recount. Eventually, the ECP ordered a recount and the tense situation abated.

Winners, losers and winners

Even with delays, denials and much confusion, the 2018 elections give some cause to celebrate. In Upper and Lower Dir, where women’s votes were previously disallowed, several women voted. All parties fielded at least five percent women on general seats. PTI’s Ghulam Bibi Bharwana and Zartaj Gul succeeded in areas where women do not usually win. PTI’s Yasmin Rashid also successfully secured a provincial seat and appeared in the running for the post of Punjab’s chief minister.

PPP’s strong women - Azra Pechuho, Faryal Talpur, Nafisa Shah, Shazia Marri - won their seats with comfortable margins.

What next?

A PTI-led government is now in the Parliament. Here, it is important to explore key political issues likely to shape the path ahead. There are three things to watch for: PTI’s coalition-building skills, its management of excluded politicians and capacity to deliver on promises.

Despite Imran Khan’s victory in five federal constituencies, his party failed to secure a majority in the National Assembly. This is something of a first for Pakistan. No other leader of a major political party has succeeded in securing wins from several federal constituencies while failing to ensure a majority win for his party. Imran Khan’s personal brand appears stronger than that of his party. It remains open to question whether Pakistan’s former cricket captain is ready for the task of coalition building and leading from behind.

For its part, the PML-N faces an existential crisis. Although its overall vote count reduced significantly, it retained some presence along its traditional stronghold around the Grand Trunk Road. As the former blue-eyed child of Pakistan’s establishment, the PML-N is a relative stranger to the politics of opposition and dissent. Although General Musharraf’s coup d’etat led to the ouster of Nawaz Sharif’s government in 1999, Sharif did not engage in much by way of dissent. He traded jail for Saudi Arabia and many of his party members defected to form the PML-Q. Several defectors returned to the PML-N after Nawaz Sharif’s return to Pakistan in 2007. For the most part, PML-N’s rank and file has enjoyed support from the army and held positions in government. Whether the PML-N members have the appetite and aptitude for opposition politics remains to be seen. From the ethnic lens, for the first time in Pakistan’s history, a mainstream Punjabi leader is standing up against the Establishment. But the overall impact of Sharif’s stance remains ambiguous.

In a curious turn of events, the old guard of Pakhtoon politics remains outside Parliament: Maulana Fazlur Rehman of JUI-F, Asfandiyar Wali of ANP, Siraj-ul-Haq of JI, Mahmood Achakzai (PkMAP) and others apparently failed to win their seats. Managing their absence from the halls of Parliament may prove difficult. A retired militaryman, who did not wish to be named, remarked, “Imran Khan calls Fazlur Rehman ‘Maulana Diesel’. Does Imran not realize that diesel is highly flammable?”