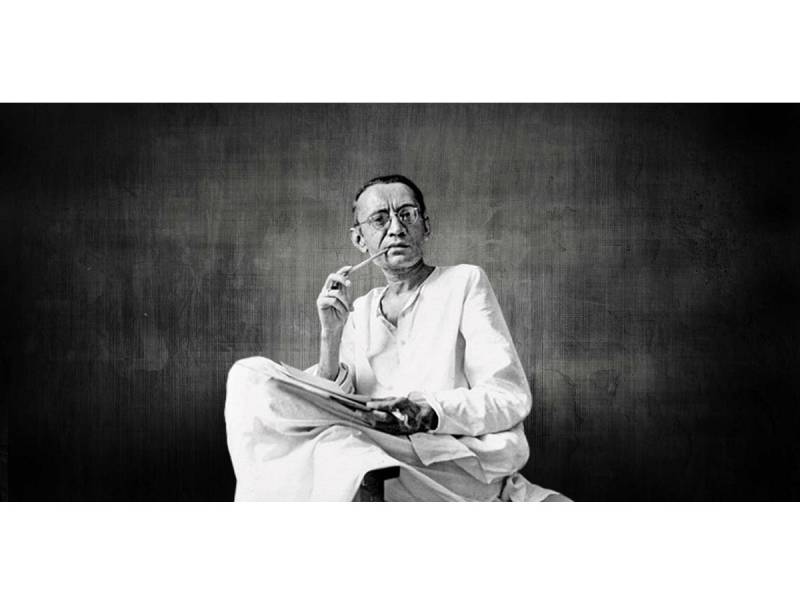

“…and it is also possible, that Saadat Hasan dies, but Manto remains alive.”

These lines belong to Manto for eternity. Inarguably, Saadat died but Manto is still alive. Throughout his work, he, like Sigmund Freud, explores the neuroticism of individuals caused by the social pressure and repression of sexual instincts.

Manto is regarded as the most acknowledged, non-conformist and distinctive short story writer in the realm of Urdu literature. He was parallel to the Progressive Writers Movement of Urdu, to which he was not opposed, but seemed to find it stifling for the uniqueness and distinctive thought in his own work. This does not mean that he sought solace under the umbrella of Regressives. He, in fact, was among the few writers, in world literature who was equally hated both by Progressives (Taraqqi Pasand) as well as Regressives (Rajat Pasand) of the time. His subjects were of a totally different kind, having instinctive representation of a brute human nature. He clothed them in the attractive clothes of humanity.

As a critic famously said, “every man is the child of his age” – Manto was no exception, and he literally lived up to it. He was distraught and disturbed by the hypocrisy of the society and bloodbaths of Partition taking place around 1947, which was one of the greatest exoduses in the history of humanity, leaving 14 millions of people displaced and approximately two millions died. He could not disremember the brutal incidents of Partition till his last breath.

Manto was born into a middle-class Muslim family in the predominantly Sikh city of Ludhiana, India, in 1912. In his early career, he translated French, Russian and English short stories into Urdu – and having been translating, he mastered the art of short story writing. His critics say that he would often complete his story in a single sitting, having had less corrections. His subjects involve various fringes of the society including the brutal incidents of partition of 1947, the mass movement of the time, sex, alcoholics, prostitutes and taboos. With such elements playing a key role in his craft, he got charged with obscenity and vulgarism six times, three times each before and after the Partition. He wrote 20 collections of stories and a novel – including plenty of scripts, sketches and essays to his credit. His life was cut short to alcoholism, and he died in 1956 at the age of 43.

His short stories are bleak and dark unflinchingly portraying the barbaric nature of human. The plot often be woven around harsh realities of life, sensationalised by blending with sexuality and the fundamental essence of human existence. This is the reason for which Manto got mired in controversies. Take, for instance, his short story Dhuvañ (Smoke) as an example. In Dhuvañ, he sheds light upon the story of an eleven- or twelve-year-old boy named Masood, who is on his way to school, sees fresh meat hanging in the shop of a butcher. The smoke is coming out from the meat, and it is splattering from some places. He comes home and explains this to his mother, but she does not show her interest. His sister, Kulsoom, is doing Riyaz in the room and when she hears Masood’s words, so she comes to him and tells him that her back is hurting, he should come and squeeze it a little. Masood agrees but insists that he will press her for ten to fifteen minutes and then leave. While squeezing her back, his body triggers fantasies of sexual awakenings. Since the theme of the story is Masood’s premature sexual awakening and psychological confusion, these things do not knock the door of Masood’s consciousness, and he goes outside to enjoy the scene of the smoky mountains as long as he encounters with the final scenes.

Dhuvañ is the best example of the conflict between psychology and sexuality of the male or female early years, whereby Manto alludes the characters to the events of the Garden between Adam and Eve, before their exile to the world. Renowned psychiatrist Doctor Akhter Ahsan eloquently wrote upon it in one of his essays.

Another example can be seen in Khol Do. The story revolves around the incidents of migration and the bloodbath of 1947, wherein Sirajuddin, the father of Sakeena, regains his consciousness, finding himself upon the barren land in a camp, recalling the brutal murder of his wife and yearning for his lost girl, Sakeena. In camp, he requests a group of young men who somehow find her on a road, where they find her attractive. Later, the scene shifts to the hospital where Sakeena is laid horizontally unconscious. Upon awakening, her hand involuntarily goes toward her Shalwar, thinking that she must open it for another one. The gang rape of Sakeena kills humanity. This is indeed a heart-wrenching story – not entirely fictitious, rather one of the real numbers of incidents coming out in the aftermath of Partition.

While drawing the lines across religion, nationality and patriarchy, Manto skilfully weaves the plot quite extraordinarily. In Thanda Gosht, the woman kills her husband who has raped a dead woman. The toxic masculinity of Ishar Singh is exposed from within the character himself satirising the communal riot and barbaric nature of the human. It is still relevant in today’s world. Empowering the woman can also be seen in his short stories as Kulwant Kaur gets committed to the death of her husband in this masterpiece. Moreover, Thanda Gosht is his only writeup for which he was convicted for profanity in Lahore.

Various literary figures of the time, including Faiz Ahmad Faiz, were summoned to court to adjudge Thanda Gosht. As to whether it was profane, Faiz replied in the negative, and added that it was not worthy of even being called a piece of literature. Manto was disappointed upon hearing this and said that it would have been better if Faiz had called it profane. He said, “If you find my stories dirty, the society you are living in is dirty. With my stories, I only expose the truth.”

Ismat Chugtai, another great literary figure, says about him in Kaghazi hai Pairahaan, “His (Manto’s) stories unsettle us because they take us to the darker, brutal corners of our psyche, to desires repressed and ugliness that settles.” By reading Manto, the reader delves into the darkest and ugliest realities of human lives. He, in other terms, offers catharsis to his readers.

Though the West might little know about Manto, the shadow of him can be seen in the aesthetics of Oscar Wilde and DH Lawrence. It seems that the souls of Wilde and Lawrence might have transmigrated into the thinner body of this literary gem of Urdu. Throughout his writeups, he portrayed human nature bluntly as no one among his contemporaries ever dared to, having less regard for hypocritical popular notions of morality.

Historian Ayesha Jalal writes in The Pity of Partition: “Whether he was writing about prostitutes, pimps or criminals, Manto wanted to impress upon his readers that these disreputable people were also human, much more than those who cloaked their failings in a thick veil of hypocrisy.”

Indeed, he wrote about them ferociously, and undoubtedly, fearlessly.