The dismal state of the economy evokes the label that is sometimes used to describe the discipline of economics: the dismal science.

Pakistan’s economy was not always in as bad a state. Today, it stands on the brink of default, international debt is at an all-time high, foreign exchange reserves are depleted, and the fiscal and trade balances are in the red. To compound the problem, inflation is raging, triggered in part by global developments.

Just about all economists agree that the economy suffers from structural imbalances. The ratio of domestic savings to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is really low and so is the ratio of taxes to the GDP. Pakistan needs to cut government spending, raise exports, and lower imports. It also needs to raise the literacy rate among the general population and raise the female labour participation rate.

Pakistan has no shortage of pedigreed economists, many of whom have worked at the Asian Development Bank, International Monetary Fund and World Bank. Pervez Hasan, who retired as the chief economist of the World Bank, is considered by many to be the brains behind Korea’s economic miracle.

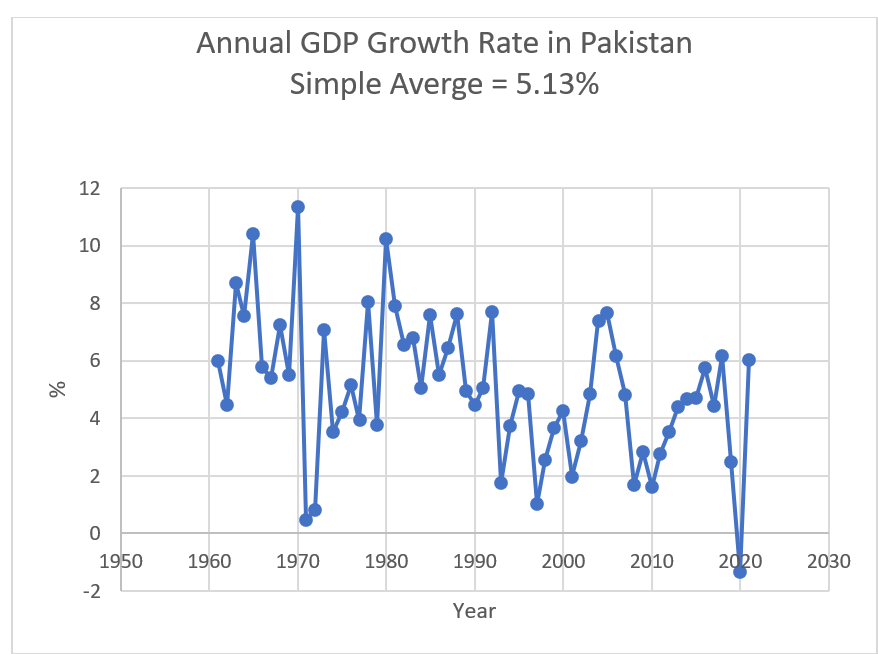

Despite their advice to successive governments in Pakistan, the country’s annual growth rate of the GDP has oscillated widely between 1961 and 2021, as shown in the chart. If we take the simple average of the annual growth rates during this period, it is 5 percent. That value is insufficient to raise per capita incomes since Pakistan’s population has grown between 2 to 3 percent a year.

A perceptible decline in the annual growth rate is visible across the six decades. During the first three decades, the simple average was 6.25 percent. It dropped by two percentage points to 4.18 percent during the second two decades.

For those who are familiar with Pakistan’s political history, it will be apparent that periods of high economic growth have tended to coincide with periods of military rule by Field Marshal Ayub Khan and Generals Zia-ul-Haq and Musharraf. It’s also noteworthy that Ayub’s period was characterised by the rise of the so-called “22 families.”

Of course, one cannot conclude that military rule has caused the growth rates to be higher, since military governments also received large amounts of financial aid, primarily from the US.

So, what is the explanation for such dismal performance? Going back to the early 1970s, when I was studying economics at the University of Karachi, two reasons were blamed for the lacklustre performance: “meagre resources” and “vested interests.”

“Meagre resources” is now a forgotten term. The term le jour for vested interests is “elite.” Dr Ishrat Husain has published a book, Pakistan: The economy of an elitist state. He worked at the World Bank for two decades, headed the State Bank of Pakistan and the Institute of Business Administration for several years.

This book, which was first issued in 1999, was reissued as a second edition in 2019. The only difference between the two editions is the inclusion of a new chapter at the end, which covers the period between 1999 and 2018. Just about all the discussion in the book ends in 1988 and at points I was wondering if I had ordered the first edition.

The book blames Pakistan’s woes on bad governance. By bad governance, it means a culture based on patronage, nepotism, and bribery. Such a culture exists because the institutions of governance are weak.

Dr. Husain says that the economy is dominated by four groups: (1) the landed aristocracy, industrialists and big business, (2) civil bureaucrats, (3) military officials, and (4) the professionals. This is not unique to Pakistan. A few groups dominate the economic landscape of many countries, including the good performers.

In the last chapter, which focuses on the last quarter century, he says these four groups have entrenched their position and continue to accumulate wealth through crony capitalism, based on a system of patronage and privilege. Governments come and go but the same people continue to be given cabinet positions. Of course, Dr Husain himself typifies that, having served in senior positions during the Musharraf and Imran Khan eras. Dr Abdul Hafeez Shaikh is another example.

In his prior book, Governing the Ungovernable, he dismissed four widely held explanations of why economic growth has been dismal in Pakistan. He did not think the military had a big presence in the nation’s economy, despite Ayesha Siddiqa’s trenchant critique, Military, Inc. He did not think the money spent on defense created a problem for the country, despite Ishtiaq Ahmed’s critique, The Garrison State, and that of several other analysts, including me. He did not criticise the military for having demolished the democratic institutions in the country, despite Aqil Shah’s critique, The Army and Democracy. And he ruled out foreign aid as one of the factors that led to high economic growth, despite Pervez Hasan’s observations.

In the new book, there is no discussion of the costs imposed on the economy by the military over spending scarce taxpayers’ money and dominating the commanding heights of the economy. The American scholar Stephen Cohen called the army the largest political party in Pakistan. Others have said that it is the only institution that works in Pakistan. Of course, that’s not true, since the army has managed to lose just all the wars it has fought with its sibling, India. Notably, the country broke up in 1971 on the army’s watch.

Pakistan’s military, with a strength of 600,000, is half of India’s. It’s oversized. To maintain a strong defense, it just needs to be a third of the size of the Indian military, which means 400,000 personnel. By right-sizing the military, the defense budget can be cut by a quarter to a third, freeing up resources for higher priority uses.

The army’s command structure is bloated, with more than 200 general officers, and if one were to count the one-star brigadiers, who are regarded as generals in many countries, the number will be closer to 600. The command structure needs to be trimmed.

The military needs to be withdrawn from all civilian duties such as owning and running large corporations and defense housing societies. Of course, the civilian government can call upon it during emergencies such as the recent floods.

In the …Elitist State book, Dr Husain puts forward a reform programme that essentially has six elements. First, replace the patronage-ridden process with one where government institutions ensure that economic growth benefits the majority of the population, the legislature passes laws that benefit the entire population, and the judiciary ensures the sanctity of contracts is preserved. Second, that the electoral process is reformed to ensure its fairness and transparency. Third, that the civil service is reformed to ensure that privilege and nepotism are rooted out. Fourth, the educational institutions are reformed to ensure that Pakistan has the best human talent to create products and services that compete in world markets. Fifth, the parliament is reformed to keep the executive branch in check. And, sixth, that the financial system is reformed so it provides access to credit to all classes of society.

The key question, not addressed in the book, is why have these ideas, all of which have been known for decades, not been implemented?

The obvious answer is that the culture of nepotism and bribery, or corruption for short, is institutionalised in Pakistan, sewn, as it were, into the social fabric of the country. From peon to chairman, everyone expects to either pay a bribe or take a bribe to get the simplest thing done. In the middle, if there is someone who neither takes a bribe or offers a bribe, he or she is frowned upon by people under him or her and also by the people over him or her. Nominally, everyone claims to be living the life of a true Muslim. To wash themselves of their sins, several bribe takers even frame a verse from the scripture on the wall behind their desk which reads, in Arabic, “This is from the Grace of My Lord.” Such is how life is lived in the Islamic Republic.

Why would the elite whose sins are so thoroughly catalogued and castigated by Dr. Husain voluntarily give up their privileges? And, if they won’t – as they haven’t for the past 75 years – who is going to disenfranchise them?

Until someone comes along who can disenfranchise them, nothing will change. Imran Khan promised to change the fundamentals of the economy. Many thought the redeemer had at last arrived. Sadly, he proved to be a false redeemer.

Pakistan’s economy was not always in as bad a state. Today, it stands on the brink of default, international debt is at an all-time high, foreign exchange reserves are depleted, and the fiscal and trade balances are in the red. To compound the problem, inflation is raging, triggered in part by global developments.

Just about all economists agree that the economy suffers from structural imbalances. The ratio of domestic savings to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is really low and so is the ratio of taxes to the GDP. Pakistan needs to cut government spending, raise exports, and lower imports. It also needs to raise the literacy rate among the general population and raise the female labour participation rate.

Pakistan has no shortage of pedigreed economists, many of whom have worked at the Asian Development Bank, International Monetary Fund and World Bank. Pervez Hasan, who retired as the chief economist of the World Bank, is considered by many to be the brains behind Korea’s economic miracle.

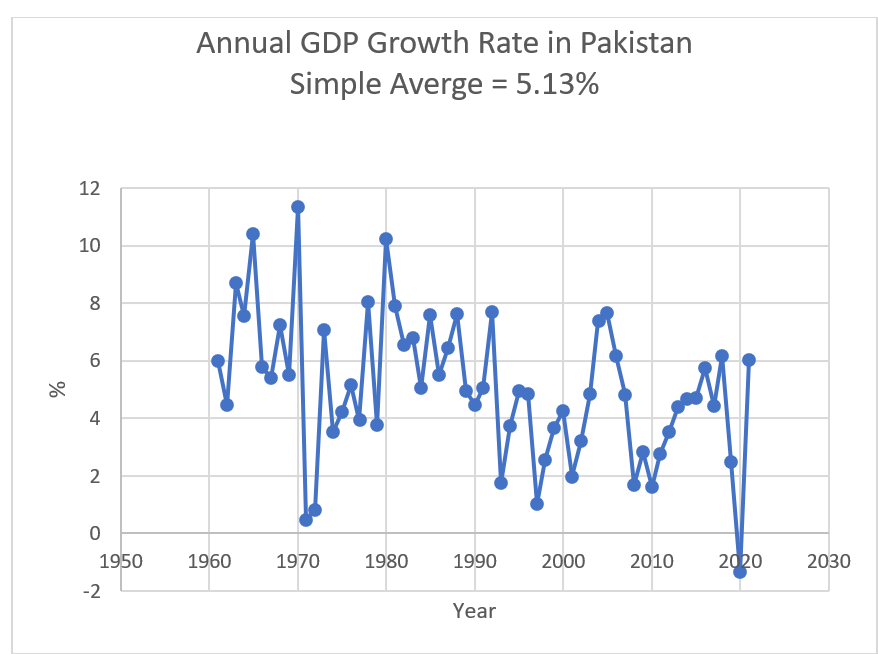

Despite their advice to successive governments in Pakistan, the country’s annual growth rate of the GDP has oscillated widely between 1961 and 2021, as shown in the chart. If we take the simple average of the annual growth rates during this period, it is 5 percent. That value is insufficient to raise per capita incomes since Pakistan’s population has grown between 2 to 3 percent a year.

A perceptible decline in the annual growth rate is visible across the six decades. During the first three decades, the simple average was 6.25 percent. It dropped by two percentage points to 4.18 percent during the second two decades.

For those who are familiar with Pakistan’s political history, it will be apparent that periods of high economic growth have tended to coincide with periods of military rule by Field Marshal Ayub Khan and Generals Zia-ul-Haq and Musharraf. It’s also noteworthy that Ayub’s period was characterised by the rise of the so-called “22 families.”

Of course, one cannot conclude that military rule has caused the growth rates to be higher, since military governments also received large amounts of financial aid, primarily from the US.

So, what is the explanation for such dismal performance? Going back to the early 1970s, when I was studying economics at the University of Karachi, two reasons were blamed for the lacklustre performance: “meagre resources” and “vested interests.”

“Meagre resources” is now a forgotten term. The term le jour for vested interests is “elite.” Dr Ishrat Husain has published a book, Pakistan: The economy of an elitist state. He worked at the World Bank for two decades, headed the State Bank of Pakistan and the Institute of Business Administration for several years.

This book, which was first issued in 1999, was reissued as a second edition in 2019. The only difference between the two editions is the inclusion of a new chapter at the end, which covers the period between 1999 and 2018. Just about all the discussion in the book ends in 1988 and at points I was wondering if I had ordered the first edition.

The book blames Pakistan’s woes on bad governance. By bad governance, it means a culture based on patronage, nepotism, and bribery. Such a culture exists because the institutions of governance are weak.

Dr. Husain says that the economy is dominated by four groups: (1) the landed aristocracy, industrialists and big business, (2) civil bureaucrats, (3) military officials, and (4) the professionals. This is not unique to Pakistan. A few groups dominate the economic landscape of many countries, including the good performers.

In the new book, there is no discussion of the costs imposed on the economy by the military over spending scarce taxpayers’ money and dominating the commanding heights of the economy.

In the last chapter, which focuses on the last quarter century, he says these four groups have entrenched their position and continue to accumulate wealth through crony capitalism, based on a system of patronage and privilege. Governments come and go but the same people continue to be given cabinet positions. Of course, Dr Husain himself typifies that, having served in senior positions during the Musharraf and Imran Khan eras. Dr Abdul Hafeez Shaikh is another example.

In his prior book, Governing the Ungovernable, he dismissed four widely held explanations of why economic growth has been dismal in Pakistan. He did not think the military had a big presence in the nation’s economy, despite Ayesha Siddiqa’s trenchant critique, Military, Inc. He did not think the money spent on defense created a problem for the country, despite Ishtiaq Ahmed’s critique, The Garrison State, and that of several other analysts, including me. He did not criticise the military for having demolished the democratic institutions in the country, despite Aqil Shah’s critique, The Army and Democracy. And he ruled out foreign aid as one of the factors that led to high economic growth, despite Pervez Hasan’s observations.

In the new book, there is no discussion of the costs imposed on the economy by the military over spending scarce taxpayers’ money and dominating the commanding heights of the economy. The American scholar Stephen Cohen called the army the largest political party in Pakistan. Others have said that it is the only institution that works in Pakistan. Of course, that’s not true, since the army has managed to lose just all the wars it has fought with its sibling, India. Notably, the country broke up in 1971 on the army’s watch.

Pakistan’s military, with a strength of 600,000, is half of India’s. It’s oversized. To maintain a strong defense, it just needs to be a third of the size of the Indian military, which means 400,000 personnel. By right-sizing the military, the defense budget can be cut by a quarter to a third, freeing up resources for higher priority uses.

The army’s command structure is bloated, with more than 200 general officers, and if one were to count the one-star brigadiers, who are regarded as generals in many countries, the number will be closer to 600. The command structure needs to be trimmed.

The military needs to be withdrawn from all civilian duties such as owning and running large corporations and defense housing societies. Of course, the civilian government can call upon it during emergencies such as the recent floods.

In the …Elitist State book, Dr Husain puts forward a reform programme that essentially has six elements. First, replace the patronage-ridden process with one where government institutions ensure that economic growth benefits the majority of the population, the legislature passes laws that benefit the entire population, and the judiciary ensures the sanctity of contracts is preserved. Second, that the electoral process is reformed to ensure its fairness and transparency. Third, that the civil service is reformed to ensure that privilege and nepotism are rooted out. Fourth, the educational institutions are reformed to ensure that Pakistan has the best human talent to create products and services that compete in world markets. Fifth, the parliament is reformed to keep the executive branch in check. And, sixth, that the financial system is reformed so it provides access to credit to all classes of society.

The key question, not addressed in the book, is why have these ideas, all of which have been known for decades, not been implemented?

The army’s command structure is bloated, with more than 200 general officers, and if one were to count one-star brigadiers, who are regarded as generals in many countries, the number will be closer to 600. The command structure needs to be trimmed.

The obvious answer is that the culture of nepotism and bribery, or corruption for short, is institutionalised in Pakistan, sewn, as it were, into the social fabric of the country. From peon to chairman, everyone expects to either pay a bribe or take a bribe to get the simplest thing done. In the middle, if there is someone who neither takes a bribe or offers a bribe, he or she is frowned upon by people under him or her and also by the people over him or her. Nominally, everyone claims to be living the life of a true Muslim. To wash themselves of their sins, several bribe takers even frame a verse from the scripture on the wall behind their desk which reads, in Arabic, “This is from the Grace of My Lord.” Such is how life is lived in the Islamic Republic.

Why would the elite whose sins are so thoroughly catalogued and castigated by Dr. Husain voluntarily give up their privileges? And, if they won’t – as they haven’t for the past 75 years – who is going to disenfranchise them?

Until someone comes along who can disenfranchise them, nothing will change. Imran Khan promised to change the fundamentals of the economy. Many thought the redeemer had at last arrived. Sadly, he proved to be a false redeemer.