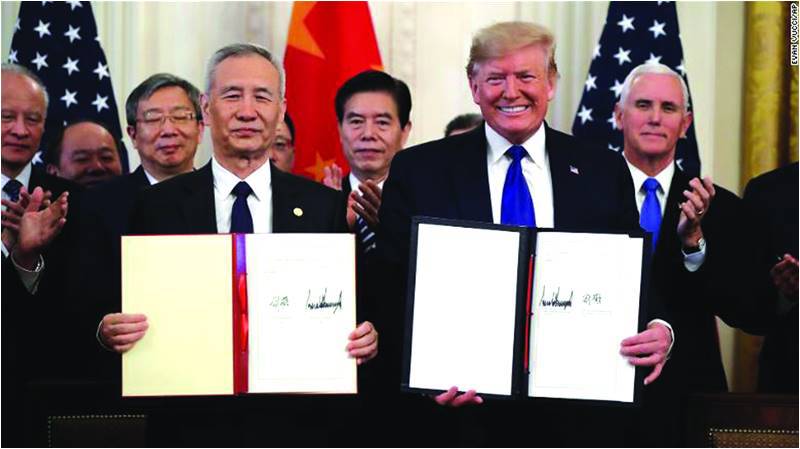

A little over a week ago, China and the US signed phase one of a trade deal that is being hailed as a sign of de-escalation of trade tensions between two of the world’s largest economies. Ever since the start of 2018, the two countries had been embroiled in an ugly trade war that was initiated by the US, after it accused China of “ripping off the US” through questionable tactics such as currency manipulation and intellectual property rights theft, both of which President Trump claimed had contributed to the $400 billion-dollar trade deficit with China.

In a series of tit-for-tat moves that began in early 2018, the two countries continued to slap restrictive tariffs on each other’s exports. While this significantly reduced US’ trade deficit with China, the spill over effects created by the trade war were not just damaging to numerous industries and consumers in both countries, but also to the global economy in general. Even though phase one of the trade agreement does not pull down any of the tariffs imposed during the trade war (except for tariffs proposed in December that were yet to take effect), it appears to be a first step towards forestalling further escalation between the two economies.

One of the most important pledges made by the Chinese include buying of an additional $200 billion worth of American goods and services over the next two years; $77bn of these would be bought in 2020, and the remaining $123bn in 2021. This $200bn is to be over and above the value of goods and services imported by China from the US in 2017, which hovered around the $180 billion mark. This means that China will have to increase its imports from the US by 42 percent in 2020, and 68 percent in 2021 in comparison to 2017 numbers, which are ambitious (if not almost improbable) targets. These additional imports by China from the US will be made up of manufactured, agricultural and energy goods, and a little below $40 billion would be from the services sector.

In addition to being ambitious, this $200 billion pledge leaves out numerous important details. So far, it seems to be a one-time affair, with no details on what would happen after 2021. There are also no details on how Chinese companies would treat their existing contracts with exporters from other countries, and how demand would need to be ramped up for these additional goods and services to be bought. Whether the Chinese will deliver on this pledge, and how they will do so remains to be seen. The agreement also differs in its conflict resolution mechanism in comparison to other trade agreements, and stipulates that any disputes will be resolved without the involvement of a third party, through a Bilateral Evaluation and Dispute Resolution Office.

There are, however, some silver linings for certain businesses in the agreement. American farmers, for instance, will breathe a sigh of relief as the Chinese have done way with long time regulatory irritants that had restricted American agricultural imports into the country. These barriers include cumbersome health standards, licensing procedures and inspection requirements. This, it is hoped, will significantly increase access of American agricultural goods to China.

The deal also bids well for credit card and electronic payment companies. Companies such as Visa, Mastercard and American Express have been trying since a long time to gain access to the Chinese market. As part of the deal, they will now be able to submit license applications with the Chinese, which was previously not possible. While the agreement does not mention that these will be automatically approved, since 2017 China has been moving towards allowing more foreign financial firms to operate in its markets. Last year, Chinese regulators had also given permission for WeChat and Alipay’s payment platforms to be accessed by foreigners using their credit cards.

An important concern that the trade agreement covers is that of intellectual property (IP) rights. American firms had since long complained about the forced transfer of technology and “trade secrets” in order to operate in the Chinese market. Furthermore, patent owners had also pointed out that confidential information was not well protected under Chinese law. The trade agreement includes commitments to halt the transfer of such information to Chinese competitors and more protection from the Chinese against such practices. It also requires China to submit an action plan within 30 days for the strengthening of IP protection, which would include details on the measures proposed by China and the date by which these will go into effect. While the provision may only exist on paper for now, it will still be considered a step forward for US interests.

Politically, bringing China to the negotiating table after a long and ugly trade war will most likely be leveraged by President Trump as a victory, since being tough on China was one of his major election promises. As he goes into the election this year, he could very well use the deal for significant political mileage. Furthermore, the deal with the Chinese creates momentum for US negotiators and puts them in a better bargaining position as they address current trade disputes with the European Union.

The Chinese will consider the non-inclusion of several important issues as a victory: the issue of subsidies provided to Chinese firms and state-owned enterprises does not appear in the agreement. American officials have mentioned that these will be part of the second phase of the agreement and may also be taken up with the World Trade Organization at a later stage. Other crucial issues related to cyber security, data storage, and cloud computing are also not part of phase one of the deal. Increased access for financial firms and greater IP protection have also been taken up by the Chinese at a time of their choosing. One could very well argue that Chinese firms are now at a more developed stage where they are not significantly dependent on American and other foreign technology.

Finally, the deal fares well for the global economy: the trade war had caused much uncertainty in the global economy, leading to postponement of investment and consumption decisions. While it would be premature to treat the agreement as a resolution of important issues and as an end of the trade war, it would definitely lead to much calm in global markets in the short-term to medium-term.

The writer is an economist

In a series of tit-for-tat moves that began in early 2018, the two countries continued to slap restrictive tariffs on each other’s exports. While this significantly reduced US’ trade deficit with China, the spill over effects created by the trade war were not just damaging to numerous industries and consumers in both countries, but also to the global economy in general. Even though phase one of the trade agreement does not pull down any of the tariffs imposed during the trade war (except for tariffs proposed in December that were yet to take effect), it appears to be a first step towards forestalling further escalation between the two economies.

One of the most important pledges made by the Chinese include buying of an additional $200 billion worth of American goods and services over the next two years; $77bn of these would be bought in 2020, and the remaining $123bn in 2021. This $200bn is to be over and above the value of goods and services imported by China from the US in 2017, which hovered around the $180 billion mark. This means that China will have to increase its imports from the US by 42 percent in 2020, and 68 percent in 2021 in comparison to 2017 numbers, which are ambitious (if not almost improbable) targets. These additional imports by China from the US will be made up of manufactured, agricultural and energy goods, and a little below $40 billion would be from the services sector.

Bringing China to the negotiating table after a long and ugly trade war will most likely be leveraged by President Trump as a victory, since being tough on China was one of his major election promises

In addition to being ambitious, this $200 billion pledge leaves out numerous important details. So far, it seems to be a one-time affair, with no details on what would happen after 2021. There are also no details on how Chinese companies would treat their existing contracts with exporters from other countries, and how demand would need to be ramped up for these additional goods and services to be bought. Whether the Chinese will deliver on this pledge, and how they will do so remains to be seen. The agreement also differs in its conflict resolution mechanism in comparison to other trade agreements, and stipulates that any disputes will be resolved without the involvement of a third party, through a Bilateral Evaluation and Dispute Resolution Office.

There are, however, some silver linings for certain businesses in the agreement. American farmers, for instance, will breathe a sigh of relief as the Chinese have done way with long time regulatory irritants that had restricted American agricultural imports into the country. These barriers include cumbersome health standards, licensing procedures and inspection requirements. This, it is hoped, will significantly increase access of American agricultural goods to China.

The deal also bids well for credit card and electronic payment companies. Companies such as Visa, Mastercard and American Express have been trying since a long time to gain access to the Chinese market. As part of the deal, they will now be able to submit license applications with the Chinese, which was previously not possible. While the agreement does not mention that these will be automatically approved, since 2017 China has been moving towards allowing more foreign financial firms to operate in its markets. Last year, Chinese regulators had also given permission for WeChat and Alipay’s payment platforms to be accessed by foreigners using their credit cards.

An important concern that the trade agreement covers is that of intellectual property (IP) rights. American firms had since long complained about the forced transfer of technology and “trade secrets” in order to operate in the Chinese market. Furthermore, patent owners had also pointed out that confidential information was not well protected under Chinese law. The trade agreement includes commitments to halt the transfer of such information to Chinese competitors and more protection from the Chinese against such practices. It also requires China to submit an action plan within 30 days for the strengthening of IP protection, which would include details on the measures proposed by China and the date by which these will go into effect. While the provision may only exist on paper for now, it will still be considered a step forward for US interests.

Politically, bringing China to the negotiating table after a long and ugly trade war will most likely be leveraged by President Trump as a victory, since being tough on China was one of his major election promises. As he goes into the election this year, he could very well use the deal for significant political mileage. Furthermore, the deal with the Chinese creates momentum for US negotiators and puts them in a better bargaining position as they address current trade disputes with the European Union.

The Chinese will consider the non-inclusion of several important issues as a victory: the issue of subsidies provided to Chinese firms and state-owned enterprises does not appear in the agreement. American officials have mentioned that these will be part of the second phase of the agreement and may also be taken up with the World Trade Organization at a later stage. Other crucial issues related to cyber security, data storage, and cloud computing are also not part of phase one of the deal. Increased access for financial firms and greater IP protection have also been taken up by the Chinese at a time of their choosing. One could very well argue that Chinese firms are now at a more developed stage where they are not significantly dependent on American and other foreign technology.

Finally, the deal fares well for the global economy: the trade war had caused much uncertainty in the global economy, leading to postponement of investment and consumption decisions. While it would be premature to treat the agreement as a resolution of important issues and as an end of the trade war, it would definitely lead to much calm in global markets in the short-term to medium-term.

The writer is an economist