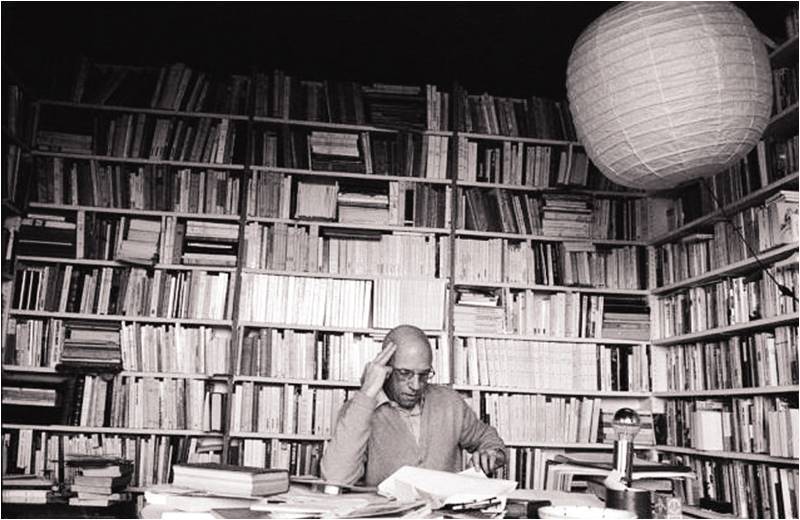

Singapore reminds me of French philosopher Michel Foucault. Foucault’s 1975 book, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, is generally considered an examination of the modern penal system. But it’s that and more. The book’s central argument is that the ruling class has moved from physical control of the ruled to a psychological approach: from the culture of spectacle to a carceral culture.

The idea of the Panopticon is central to Foucault’s work, a concept presented by British philosopher, Jeremy Bentham. Bentham’s panopticon was a prison building with several inward-looking cells and a watchtower standing in the centre. The idea was that the prisoners could not see the guards while the guards could monitor the inmates without being seen.

Foucault expanded the concept to mean much more than just a confined, physical space. For instance, he used the concept of a “carceral archipelago”— an open prison consisting of a series of islands. The idea was to stress the point about how the ruling class could take control of public spaces and minimise disciplinary infractions. Because the inmates would assume that they are being watched at all times, they would behave and that would reduce the need for prison guards.

This, according to Foucault, was very different from the medieval times when monarchs exercised control over the body, using torture and spectacle as deterrence. The book opens with the description of a scene in Paris where Robert-François Damiens is being horrifically and publicly tortured and put to death for attempted regicide.

There are multiple themes in Foucault’s work, but the central one is the relationship between the prison and the society. The prison is not an isolated, marginal structure on the periphery. It is closely knit into the city. The same “strategies” — Foucault’s term — of power and knowledge operate both in the periphery and the city. The delinquent (the prisoner), his punishment, and the mechanisms of discipline are also meant to control the citizen because the latter is supposed to stay in line by looking at the former. This is psycho-social control of the body and mind. To this end, Foucault mentions the various methods of observation and control that originated in monasteries and army barracks.

Corollary: the prison is central to the idea of streamlining society because it denotes our ways of thinking about and meting out punishment. In other words, the prison is part of a “carceral network” that permeates through society and controls it.

This is meant to produce docile bodies. Discipline produces docility. It does not rely primarily on force or violence; it is a set of rules meant to control the body in a way that the body internalises the set of rules as beneficial to it, even characterising its (body’s) existence. The metaphors for it are monastic rules, drill exercises in the army et cetera. There’s the element of the coercive in the idea of punishment, but in its essence it is about societal acceptance of what is presented as dos and don’ts.

This links up with Foucault’s argument that reformers of punishment in the 18th century were not concerned about the welfare of the prisoners. They wanted a system where power could be exercised more efficiently and comprehensively.

But while Foucault uses the term ruling class, modern carceral network — a lot of it now in the name of security — impacts everyone, the ruled as much as the rulers. Prisons aren’t the only spaces where people can be confined and watched. Everyone is now in a panopticon. The monitoring, increasingly, relies as much on laws, rules and regulations, as on gadgets: EMV IC cards, QR matrix barcodes, smartphones, cameras, radio-frequency identification systems et cetera.

The internalisation and socialisation of discipline works in myriad ways. But its end result is docile bodies. Some are entirely docile, others are less so. But systems increasingly, as Foucault noted, ensnare us into accepting what’s considered legal or illegal, good behaviour or delinquent one.

There’s an interesting anecdote in James C Scott’s Two Cheers for Anarchism. Scott says, “Judging when it makes sense to break a law requires careful thought even in the relatively innocuous case of jaywalking.” He then goes on to tell the story of crossing a street when the light was against them. Scott looked around and stepped into the street. As he did that, Dr Wertheim, a Dutch philosopher with him, said, “James, you must stop.” James feebly protested and said, “But, Dr Wertheim, nothing is coming.” “James,” he replied, “ It would be a bad example for the children.”

There’s a paradox here. Clearly, people cannot live and interact without some modicum of rules and normative behaviour. Without some structures, it would be mayhem. Equally, however, a regime laden with all sorts of rules would become controlling and soulless. It would also begin to turn people into unquestioning automatons.

I began with Singapore. As I checked into the plush hotel in Sentosa, I asked for a smoking room. The receptionist said the hotel had no smoking rooms. So, I said, sure. I would use the balcony. She vehemently shook her head and said, “Sir, you can’t smoke on the balcony.” “And why can I not smoke on the balcony; it’s open area,” I said. “Because, sir, there are only three designated areas in the hotel where you can smoke.”

So, I asked her if she or anyone else had questioned the absurdity of that rule. No, she hadn’t. “It’s the rule, sir.” She had internalised it. Smokers are delinquents and smoking is injurious and, therefore, they must be reduced to the status of pariahs. There was no way I could tell her that a smoker cannot have his tea at Level 11 and then come down to Levels 5, 3 or 1 to have his cigarette. That when they wake up, while they can go to the balcony, morning cup of tea in hand, and smoke there, you can’t subject them to the torture of de-mating their cigarettes and the morning tea.

But this is precisely how it works. As I entered my room, I saw the punitive sign too: anyone breaking the rule would be fined SGD 450! Foucault argued that the punitive signs rest on six rules. At least two of those work in this case: The rule of minimum quantity: the delinquent (in this case, me!) should have more interest in avoiding the penalty than in risking breaking the rule (SGD 450 is enough for someone earning in rupees!); The rule of optimal specification: offences must be precisely classified.

So, here I am, stuck in this rules-heavy, obscenely-expensive island, yearning for the chaotic life of Lahore. There was one rule in Eden: the Forbidden fruit, a metaphor for the state of simple consciousness. When Adam and Eve ate it, they moved to the state of self-consciousness. The story that began with an infraction to save the human spirit is slowly ending with humans losing their spiritedness and individuality in a plethora of rules, the punitive signs and punishment. Existence, thy name’s docility now. Mustapha Mond wins!

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times, regretting his decision to attend a conference in Singapore. He reluctantly tweets @ejazhaider

The idea of the Panopticon is central to Foucault’s work, a concept presented by British philosopher, Jeremy Bentham. Bentham’s panopticon was a prison building with several inward-looking cells and a watchtower standing in the centre. The idea was that the prisoners could not see the guards while the guards could monitor the inmates without being seen.

Foucault expanded the concept to mean much more than just a confined, physical space. For instance, he used the concept of a “carceral archipelago”— an open prison consisting of a series of islands. The idea was to stress the point about how the ruling class could take control of public spaces and minimise disciplinary infractions. Because the inmates would assume that they are being watched at all times, they would behave and that would reduce the need for prison guards.

This, according to Foucault, was very different from the medieval times when monarchs exercised control over the body, using torture and spectacle as deterrence. The book opens with the description of a scene in Paris where Robert-François Damiens is being horrifically and publicly tortured and put to death for attempted regicide.

There are multiple themes in Foucault’s work, but the central one is the relationship between the prison and the society. The prison is not an isolated, marginal structure on the periphery. It is closely knit into the city. The same “strategies” — Foucault’s term — of power and knowledge operate both in the periphery and the city. The delinquent (the prisoner), his punishment, and the mechanisms of discipline are also meant to control the citizen because the latter is supposed to stay in line by looking at the former. This is psycho-social control of the body and mind. To this end, Foucault mentions the various methods of observation and control that originated in monasteries and army barracks.

Corollary: the prison is central to the idea of streamlining society because it denotes our ways of thinking about and meting out punishment. In other words, the prison is part of a “carceral network” that permeates through society and controls it.

This is meant to produce docile bodies. Discipline produces docility. It does not rely primarily on force or violence; it is a set of rules meant to control the body in a way that the body internalises the set of rules as beneficial to it, even characterising its (body’s) existence. The metaphors for it are monastic rules, drill exercises in the army et cetera. There’s the element of the coercive in the idea of punishment, but in its essence it is about societal acceptance of what is presented as dos and don’ts.

This links up with Foucault’s argument that reformers of punishment in the 18th century were not concerned about the welfare of the prisoners. They wanted a system where power could be exercised more efficiently and comprehensively.

But while Foucault uses the term ruling class, modern carceral network — a lot of it now in the name of security — impacts everyone, the ruled as much as the rulers. Prisons aren’t the only spaces where people can be confined and watched. Everyone is now in a panopticon. The monitoring, increasingly, relies as much on laws, rules and regulations, as on gadgets: EMV IC cards, QR matrix barcodes, smartphones, cameras, radio-frequency identification systems et cetera.

The internalisation and socialisation of discipline works in myriad ways. But its end result is docile bodies. Some are entirely docile, others are less so. But systems increasingly, as Foucault noted, ensnare us into accepting what’s considered legal or illegal, good behaviour or delinquent one.

There’s an interesting anecdote in James C Scott’s Two Cheers for Anarchism. Scott says, “Judging when it makes sense to break a law requires careful thought even in the relatively innocuous case of jaywalking.” He then goes on to tell the story of crossing a street when the light was against them. Scott looked around and stepped into the street. As he did that, Dr Wertheim, a Dutch philosopher with him, said, “James, you must stop.” James feebly protested and said, “But, Dr Wertheim, nothing is coming.” “James,” he replied, “ It would be a bad example for the children.”

There’s a paradox here. Clearly, people cannot live and interact without some modicum of rules and normative behaviour. Without some structures, it would be mayhem. Equally, however, a regime laden with all sorts of rules would become controlling and soulless. It would also begin to turn people into unquestioning automatons.

I began with Singapore. As I checked into the plush hotel in Sentosa, I asked for a smoking room. The receptionist said the hotel had no smoking rooms. So, I said, sure. I would use the balcony. She vehemently shook her head and said, “Sir, you can’t smoke on the balcony.” “And why can I not smoke on the balcony; it’s open area,” I said. “Because, sir, there are only three designated areas in the hotel where you can smoke.”

So, I asked her if she or anyone else had questioned the absurdity of that rule. No, she hadn’t. “It’s the rule, sir.” She had internalised it. Smokers are delinquents and smoking is injurious and, therefore, they must be reduced to the status of pariahs. There was no way I could tell her that a smoker cannot have his tea at Level 11 and then come down to Levels 5, 3 or 1 to have his cigarette. That when they wake up, while they can go to the balcony, morning cup of tea in hand, and smoke there, you can’t subject them to the torture of de-mating their cigarettes and the morning tea.

But this is precisely how it works. As I entered my room, I saw the punitive sign too: anyone breaking the rule would be fined SGD 450! Foucault argued that the punitive signs rest on six rules. At least two of those work in this case: The rule of minimum quantity: the delinquent (in this case, me!) should have more interest in avoiding the penalty than in risking breaking the rule (SGD 450 is enough for someone earning in rupees!); The rule of optimal specification: offences must be precisely classified.

So, here I am, stuck in this rules-heavy, obscenely-expensive island, yearning for the chaotic life of Lahore. There was one rule in Eden: the Forbidden fruit, a metaphor for the state of simple consciousness. When Adam and Eve ate it, they moved to the state of self-consciousness. The story that began with an infraction to save the human spirit is slowly ending with humans losing their spiritedness and individuality in a plethora of rules, the punitive signs and punishment. Existence, thy name’s docility now. Mustapha Mond wins!

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times, regretting his decision to attend a conference in Singapore. He reluctantly tweets @ejazhaider