As January rolls into February, most areas in northern Pakistan are usually blanketed by a thick layer of pristine, white snow. But this year, there has been little to no snowfall.

In what is being seen as one of the most profound manifestations of climate change after experiencing one of the hottest years on record, the lack of snow has set off alarm bells amongst Pakistan's mountain communities and environmental experts.

The north of Pakistan is the only country to host three of the world's highest mountain ranges: the Hindu Kush, the Karakoram and the Himalayas. They converge to a single point in Gilgit Baltistan and form a big chunk of the world's "third pole" — the largest body of glacial ice outside the northern and southern poles.

Snow here is not just a climatic feature but a source of replenishing the proverbial water towers of the region, which feed rivers such as the mighty River Indus, a major lifeline for Pakistan and adjoining countries.

Snowless valleys of the Hindu Kush

"I am looking at the 4,000 feet Gori Moon hill," says 35-year-old Arif Ullah tells The Friday Times via telephone from the remote Bumburet village in the scenic Kalash valley of Chitral at the footsteps of the Hindu Kush mountain range in northwestern Pakistan.

The Hindu Kush mountain range starts in Pakistan and stretches 800 kilometres into southern Tajikistan and northeastern Afghanistan.

This time last year in January, Arif said, the Gori Moon was fully decked out in white, powdery snow. This year, he said, it is still waiting for a speck of white.

"If the snowfall does not occur in January, it will be a matter of great concern," he said, adding that usually, they receive the first snowfall of the winter season in October. Spring makes its way into the valley by April.

"Our entire system is dependent on snow," he told The Friday Times, noting that in recent years, all the seasons, rain and snowfall have not followed the usual patterns.

Arif Ullah currently works as a manager at a micro-hydel project in Chitral, which is operated by the non-governmental organisation Sarhad Rural Support Programme (SRSP). He is also involved in social developmental activities in the Kalash Valley. He saw firsthand the impact of reduced snow in Chitral on their mountain lifecycle, most profoundly in the form of water scarcity.

"Our livestock, agriculture and tourism, all are dependent on mountain snow," he said, adding that many natural water springs in Upper Chitral have dried up since 2015, but the authorities failed to take an interest in resolving the issue.

Reduced snow also contributes to weaker streams and water scarcity, Arif pointed out. He said that the situation was so bad in some areas that the lower volumes and weaker water pressure produced less power from the turbines for the local communities, leading to outages.

Can you ski down a snowless hillside in Malam Jabba?

Heavy snow, in many parts of Pakistan, shuts down life. But on the slopes of Malam Jabba in Swat, some 250 kilometres southeast of Chitral, snow brings hundreds of thrill-seeking tourists every year.

Gliding down its snow-covered slopes on skis or snowboards, skating on ice and taking rides on the chairlift are all key to sustaining the tourism-fuelled local ecosystem.

Imagine then what would happen to this ecosystem when this hill station in the Hindu Kush mountain range does not receive snowfall?

Toseeq Gulshan, a resident of Malam Jabba and a local journalist, told The Friday Times via telephone that usually, the hill station sees the first snowfall in October and is completely covered in December. By the new year, the resort is teeming with tourists.

But deep into January, they are still waiting for the first snow of the season.

Snowfall is associated with livelihood in Malam Jabba, he said. Even though locals find their daily lives disturbed by the heavy snow, they welcome the livelihood associated with it.

The fluctuation in weather patterns is starting to worry locals, Gulshan said.

Kurram's snowless Spin Ghar

During the 2022-2023 winter season, the Kurram district in western Khyber Pakhtunkhwa received heavy snow.

Kurrram is no stranger to snow. The Spin Ghar mountain range in the district, which straddles the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, is Pashto for "white mountain" — to signify the snow-capped peaks in the mountain range that is located just south of the Hindu Kush.

But the range and Kurram have yet to witness any snowfall in the ongoing winter season.

Snow normally starts falling here in November, and the winter season ends in April, says Adnan Haider, a local multimedia journalist.

He told The Friday Times that the snowfall has been quite delayed this year.

The 26-year-old journalist said that he remembers how the district capital of Parachinar used to be covered with a heavy blanket of snow. But in recent years, he said the snow does not fall as heavily as it used to.

Haider said heavy rains also accompanied the heavy snowfall last year. But this year, there has been neither rain nor snow, which could impact local agriculture as water availability is an issue.

GB, the abode of mighty mountains

In northern Pakistan, the Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) region serves as the junction for three of the mightiest mountain ranges in the world: the Himalayas -- in Pakistan it hosts the ninth tallest mountain in the world, Nanga Parbat, the Karakorum -- the home of the world's second tallest mountain K2 and other peaks over 8,000 metres -- and the Hindu Kush.

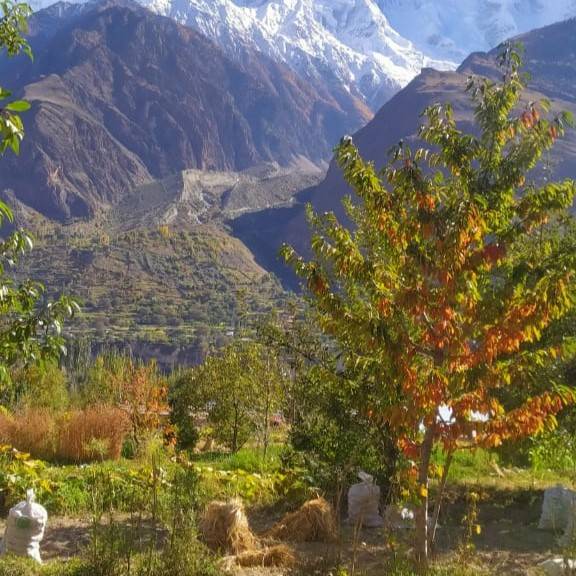

Nestled between these skyscraping mountain ranges lies the Hunza Valley. A region located at a height of 2,438 metres, it has yet to see snow this season, much like Kalash, Swat and Kurram to the west.

Sajjad Ahmad, a resident of the Murtazabad village in the valley, explained to The Friday Times that snow meant water, and water meant life for them.

The 45-year-old, who works for a private mining company in the Hunza Valley, echoed that the mountainous region has been receiving less snow yearly.

In the past, he said, heavy snow would cause schools to close for an extended period.

But the problems do not cease at a lower volume of snow. Ahmad said that the snow and glaciers are melting at a faster rate as well as global temperatures rise.

When there is reduced snowfall, he said it means reduced availability of water for residents of the region.

Ahmad also shared a recent video from GB with The Friday Times, which shows the 7,788 metre Rakaposhi mountain top still awaiting the season's first snowfall.

PMD confirms decrease in snowfall

Pakistan Meteorological Department's (PMD) Director General (DG) Mahr Sahibzad Khan confirmed to the The Friday Times that per their data, Pakistan has seen a reduction in the snowfall received in the past five years.

"Our records show temperatures in Pakistan are higher than in the past decade. And if we look at the records since 1950, the precipitation rate has increased, while snowfall has decreased over the past five years," he said, adding that their data shows average snowfall has fallen to a level below 51.4 inches per year.

He added that an increase in rain has accompanied the reduction in snowfall. To illustrate his point, he said that in the past, light rains were witnessed to spread over four to five days when winter began. Now, the rain showers have increased in intensity and precipitation. Rain recorded over four to five days now pours in just a few hours. This has increased the risk of flash floods in rural and urban areas.

The PMD chief said that apart from a change in the volume of snowfall received, the times it snows and its duration have also changed, just like the rains.

He said that these were indications that the country may experience extreme weather events of varying intensity and frequency in the future.

Mahr added that leading scientists worldwide and United Nations agencies have declared 2023 to be the hottest year on record and expect that the situation will worsen in the coming years, Mahr said, adding that the rise in global average temperatures was allied with widespread changes in weather patterns witnessed in Pakistan.

We cannot hide from climate change, the DG told The Friday Times, adding that climate change is a global issue caused by rising temperatures.

"Our records show that the overall temperature in the country is rising," he said, adding that while people living in cities complain about the cold weather, this year in GB, the temperatures have been warmer than usual, which could threaten the delicate ecosystem there.

With 2023 breaking the record set in 2016 as the warmest year ever, Mahr said that the higher temperatures were causing extreme weather events such as devastating glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs) in the Hunza Valley.

"We have a small window. We cannot hide from climate change. We must change our lifestyles," he stated, adding that it was important to understand the correlation between waste management, rapid urbanisation, industrial growth, effluents and vehicular emissions and the environment and how it was leading to climate change.