Scientists are working on different strategies to curb the COVID-19 pandemic. With drugs and vaccines being discussed in global media almost everyday, experts are saying that herd immunity also has the potential to control this pandemic.

But what does this concept – used by politicians, commentators and experts alike – actually refer to?

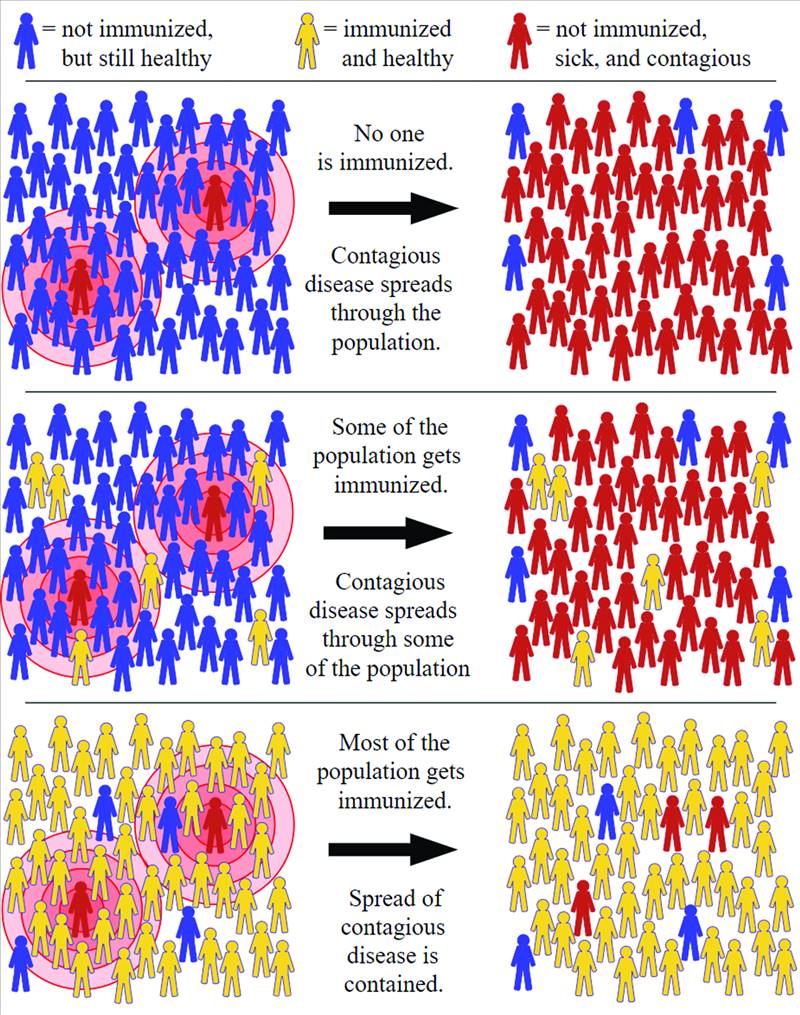

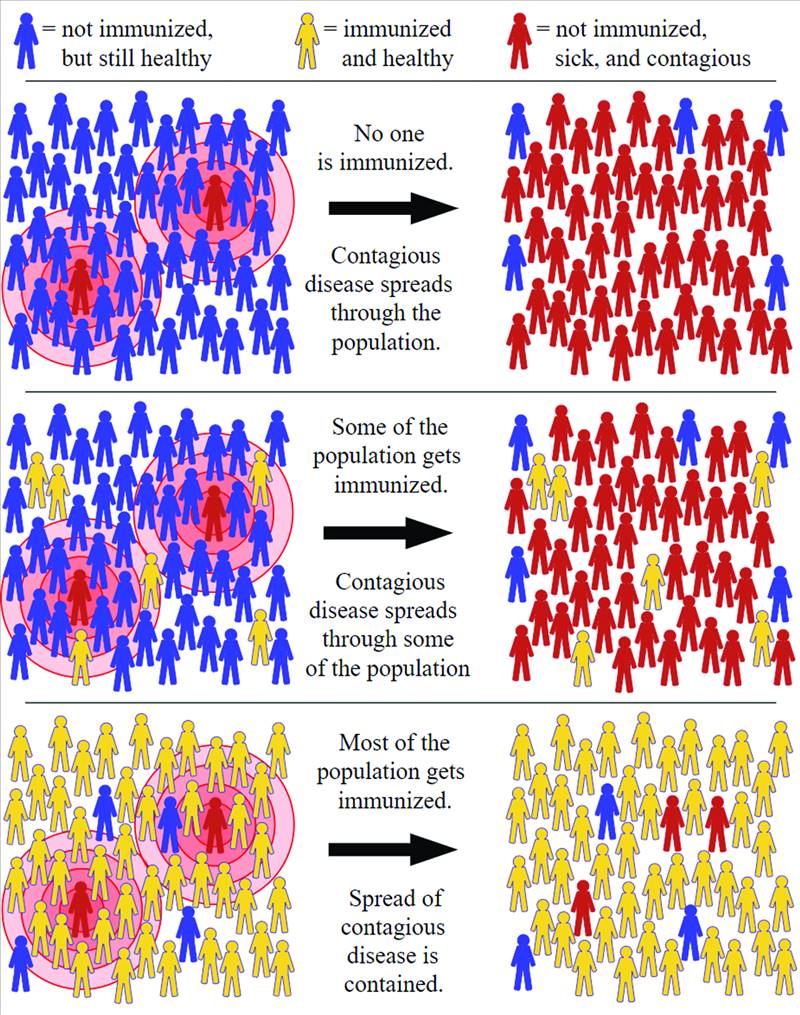

When a large population within a community (a ‘herd’) develops immunity against a disease, making the transmission of that disease from person to person less likely, the whole community becomes more secure: not just those who are immune. This state is called herd immunity.

To get to this point, a certain percentage of the population must be infected: and this is called the threshold proportion. If the level of immunity passes a certain threshold, then the pandemic will start to diminish as there are not enough new individuals to infect.

There are two routes to get herd immunity for any disease including COVID-19, i.e. vaccination and natural infection.

A vaccine is an ideal approach to get us to herd immunity. This is because vaccines provide immunity without illness or complications that may lead to death – thus avoiding the risks from natural infection. Herd immunity through vaccines has successfully controlled many lethal contagious diseases like measles, smallpox, polio etc. Some vaccines need booster injections after a certain period, failing which may reduce the immunity level in that individual and they may become infected. If the herd immunity threshold is disturbed by such oversight, it can result in the spread of that disease. For example, measles have re-emerged in some parts of the world.

Herd immunity through vaccination also has some challenges and even outright opposition to contend with. For example, in Pakistan, some communities have refused to take polio vaccines due to fears and distrust.

The second path to herd immunity is through natural infection – which is acquired when a certain level of the population recovers from an infection and develops immunity. For example, people who survived the 1918 pandemic of Spanish Flu were immune against H1N1, another type of influenza.

A very important question is: what percentage of a population is required to be immune for herd immunity?

It depends on the contagiousness of the disease. In other words, those diseases which are more contagious require a greater proportion of the population to be immune if we are to stop the infection. For example, measles is a highly contagious disease and 94% of the population is required to be immune so as to disrupt the spread of the disease.

Defining the threshold for COVID-19 is critical. To calculate this, we need to know on average how many new people are infected by each infected individual. This number is called R0 (R naught). If you obtain R0, then you can put it in a simple formula to calculate the threshold required for herd immunity i.e. 1 - 1/ R0. We know that a general R0 for COVID-19 was 2.5 (it may vary from country to country): meaning that one person can infect 2.5 individuals (on average). So, in this scenario, the threshold for herd immunity is 0.6 or 60%. It does not mean that COVID-19 will die immediately after 60% of the population develops immunity against it - but it may go on to infect another 20% before it completely vanishes.

The process of attaining herd immunity against COVID-19 through natural infection needs some more questions to be answered.

First, it is not clear yet whether individuals who recovered from COVID-19 have developed immunity against future infection. There are some reports of reinfection in recovered persons. Therefore, detailed studies are required to verify the protective immunity against the coronavirus in recovered individuals.

A second question is how long this immunity will protect the individuals from future infection. This also requires more investigation on recovered individuals.

Let us assume that COVID-recovered individuals develop long-lasting immunity. It still leaves behind a question about the consequences of COVID-19 in a large proportion of the population that need to be infected for us to reach the herd immunity threshold. According to scientists, the US requires 70% of the population (more than 200 million people) to have recovered from COVID-19 to control this pandemic. Similarly, in Pakistan we may need around 150 million people to have recovered.

These are huge numbers and hospitals could easily be exhausted before we reach it. Moreover, this route could lead to millions of deaths worldwide especially among chronically ill and older people.

Understandably, then, experts believe that reaching herd immunity without a vaccine can be calamitous. Therefore, vagueness about the naturally developed herd immunity threshold and the consequences of illness due to COVID-19 limit us with only one way forward: to follow all SOPs provided by the World Health Organization (WHO) and our government, so as to prevent surges in new cases until the development of a vaccine which can offer a safe way of getting herd immunity.

The author is Assistant Professor in Virology at the Department of Biology, College of Science, University of Bahrain

But what does this concept – used by politicians, commentators and experts alike – actually refer to?

When a large population within a community (a ‘herd’) develops immunity against a disease, making the transmission of that disease from person to person less likely, the whole community becomes more secure: not just those who are immune. This state is called herd immunity.

To get to this point, a certain percentage of the population must be infected: and this is called the threshold proportion. If the level of immunity passes a certain threshold, then the pandemic will start to diminish as there are not enough new individuals to infect.

There are two routes to get herd immunity for any disease including COVID-19, i.e. vaccination and natural infection.

A vaccine is an ideal approach to get us to herd immunity. This is because vaccines provide immunity without illness or complications that may lead to death – thus avoiding the risks from natural infection. Herd immunity through vaccines has successfully controlled many lethal contagious diseases like measles, smallpox, polio etc. Some vaccines need booster injections after a certain period, failing which may reduce the immunity level in that individual and they may become infected. If the herd immunity threshold is disturbed by such oversight, it can result in the spread of that disease. For example, measles have re-emerged in some parts of the world.

Herd immunity through vaccination also has some challenges and even outright opposition to contend with. For example, in Pakistan, some communities have refused to take polio vaccines due to fears and distrust.

The second path to herd immunity is through natural infection – which is acquired when a certain level of the population recovers from an infection and develops immunity. For example, people who survived the 1918 pandemic of Spanish Flu were immune against H1N1, another type of influenza.

A very important question is: what percentage of a population is required to be immune for herd immunity?

It depends on the contagiousness of the disease. In other words, those diseases which are more contagious require a greater proportion of the population to be immune if we are to stop the infection. For example, measles is a highly contagious disease and 94% of the population is required to be immune so as to disrupt the spread of the disease.

It is not clear yet whether individuals who recovered from COVID-19 have developed immunity against future infection. There are some reports of reinfection in recovered persons

Defining the threshold for COVID-19 is critical. To calculate this, we need to know on average how many new people are infected by each infected individual. This number is called R0 (R naught). If you obtain R0, then you can put it in a simple formula to calculate the threshold required for herd immunity i.e. 1 - 1/ R0. We know that a general R0 for COVID-19 was 2.5 (it may vary from country to country): meaning that one person can infect 2.5 individuals (on average). So, in this scenario, the threshold for herd immunity is 0.6 or 60%. It does not mean that COVID-19 will die immediately after 60% of the population develops immunity against it - but it may go on to infect another 20% before it completely vanishes.

The process of attaining herd immunity against COVID-19 through natural infection needs some more questions to be answered.

First, it is not clear yet whether individuals who recovered from COVID-19 have developed immunity against future infection. There are some reports of reinfection in recovered persons. Therefore, detailed studies are required to verify the protective immunity against the coronavirus in recovered individuals.

A second question is how long this immunity will protect the individuals from future infection. This also requires more investigation on recovered individuals.

Let us assume that COVID-recovered individuals develop long-lasting immunity. It still leaves behind a question about the consequences of COVID-19 in a large proportion of the population that need to be infected for us to reach the herd immunity threshold. According to scientists, the US requires 70% of the population (more than 200 million people) to have recovered from COVID-19 to control this pandemic. Similarly, in Pakistan we may need around 150 million people to have recovered.

These are huge numbers and hospitals could easily be exhausted before we reach it. Moreover, this route could lead to millions of deaths worldwide especially among chronically ill and older people.

Understandably, then, experts believe that reaching herd immunity without a vaccine can be calamitous. Therefore, vagueness about the naturally developed herd immunity threshold and the consequences of illness due to COVID-19 limit us with only one way forward: to follow all SOPs provided by the World Health Organization (WHO) and our government, so as to prevent surges in new cases until the development of a vaccine which can offer a safe way of getting herd immunity.

The author is Assistant Professor in Virology at the Department of Biology, College of Science, University of Bahrain