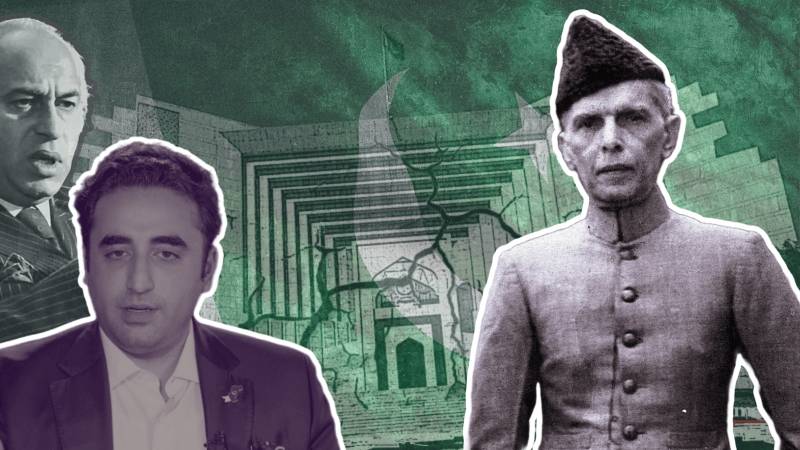

A few days ago the chief of the Pakistan People's Party (PPP), Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, posted on the social media site 'X' (formerly known as Twitter) that Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah had spoken of a Federal Court that would be separate from the Supreme Court. Bilawal's reference was to lend credence to the under-deliberation legislation which would amend the Constitution to create a Federal Constitutional Court.

Many people don't quite appreciate it when one discusses or debates Jinnah in this country. "Let the poor man rest," they say or "he is long dead". Thomas Jefferson died in 1826, and Alexander Hamilton was fatally shot in 1804. Yet Americans continue to debate and discuss their ideas, especially the Federalist Papers, more than 200 years later. Jinnah left a voluminous record of his interventions and speeches that touched almost every constitutional subject during his 41 years as an active lawyer, politician and legislator. It is a great tragedy that Pakistanis remain woefully ignorant of his work. The common refrain is that Jinnah didn't write a book. Jinnah's collected works and speeches contain much more than a mere book, but one would need to read – something Pakistanis, even our self-styled public intellectuals, are not in the habit of doing.

I said that if you separate your Federal Court, and if you will, in making appointments, select the personnel of that court which will be specially qualified in matters arising out of the Constitution, you will then, I think, set up a court which will be the most desirable court - Muhammad Ali Jinnah at the second Round Table Conference

The speech which Bilawal Bhutto refers to came during a debate at the second Round Table Conference in a discussion on the Federal Court and its powers in October 1931. The debate went on for days.

Explaining his position, Jinnah said "I said that if you separate your Federal Court, and if you will, in making appointments, select the personnel of that court which will be specially qualified in matters arising out of the Constitution, you will then, I think, set up a court which will be the most desirable court. We know, Sir, that this is an age of specialists. In India, we have not yet risen to that height. You will be surprised to hear – and I think my friends here will bear me out- in India, in the morning, you are arguing a complicated question of Hindu Law, and, in the afternoon, you are dealing with a case of light and air and easements, and perhaps the next day you are dealing with a case of a commercial kind, and a third day, perhaps you are dealing with a divorce action, and a fourth day you are dealing with an admiralty action…

Therefore, what I was suggesting was this, that we should not lose sight of the fact that there is a very strong feeling in India for a court of appellate jurisdiction which should take the place of the Privy Council- a very strong feeling- and that court must come and must be constituted. But constitute that court, against, proceedings on the lines of specialisation. There, we want men well versed in civil laws – the general civil laws – and you will, therefore, have to constitute that court having regard to its requirements. I would suggest that you should have a Supreme Court having appellate jurisdiction over the provincial high courts, in other words, in one sentence, that court should take the place of the Privy Council – namely, the appeals should lie under the same terms and conditions as the appeals lie now to the Privy Council from various high courts in India. It would not make any difference in the way of number or expenses, because, if you are going to jumble up everything in one court, the work has got to be done, and you require a number of men to do the work- whether you separate or whether you jumble up, I do not think you will save in cost or in the number of judges. Therefore, I say, let us develop the idea of a separate Supreme Court having the same jurisdiction as the Privy Council has now."

Jinnah also said that appointments to both the Federal Court and the Supreme Court should be made by the federal legislature and not the Crown. Evidently, Jinnah was a believer in the idea of parliamentary sovereignty, even over other branches of government

It is clear from the foregoing that Jinnah wanted at least two courts at the apex, i.e. a Supreme Court as the appellate court for the high courts and the Federal Court for constitutional matters and redressal of grievances of the subjects, i.e. citizens. In the same discussion, Jinnah also said that appointments to both the Federal Court and the Supreme Court should be made by the federal legislature and not the Crown. Evidently, Jinnah was a believer in the idea of parliamentary sovereignty, even over other branches of government and did not believe that it would violate the much-touted separation of powers principle and independence of the judiciary.

Bilawal Bhutto is, therefore, right on the money when he says that Jinnah wanted a separate Federal Constitutional Court, but to what end?

A word here about this selective use of the Quaid-e-Azam and his sayings. Jinnah, in my humble opinion as a biographer of the man, would never have endorsed the Constitution of 1973 in its present form. Enough evidence has been marshalled to show that Jinnah would not have endorsed the very idea of an Islamic Republic – he had told Raja of Mahmudabad that any attempt to set up an Islamic State would lead to the dissolution of the state- and he certainly would not have endorsed having a state religion as the Constitution of 1973 does. Jinnah showed, by making his famous changes to the oaths of office, that he would not countenance any bar on any citizen of Pakistan, whatever faith or lack thereof, to hold the highest office in the land. The Constitution of 1973 bars non-Muslims from holding the offices of the President and Prime Minister.

Finally, you have the Second Amendment, which violates the fundamental basis on which Pakistan was sought and won, i.e. the idea of an ontologically emptied Islam. The Second Amendment violates Jinnah's numerous promises on freedom of religion and equality, especially those promises he both explicitly and impliedly made with the Ahmadiyya community before the Partition. While it is all well and good to parade Jinnah's views on the Federal Constitutional Court, perhaps the PPP and its present leadership will realise that their founder chairman, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and his parliament in the 1970s have done grievous harm to Jinnah's vision of Pakistan.

Jinnah is both the prisoner and victim of Pakistanis. The country is too far gone to realise his ideas, especially on the constitution and fundamental rights

Talking of federal courts, what would Jinnah have made of the Federal Shariat Court, a court comprising of religious reactionaries and priests with a divine mission sitting in judgment over the legislature's general will? He repeatedly said that Pakistan shall not be a theocracy to be run by priests with a divine mission. Pakistan today is a theocracy and not of a gentle kind. It is a totalitarian and fascist theocracy that persecutes those who dare to think differently.

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru wrote in his book Discovery of India: "MA Jinnah himself was more advanced than most of his colleagues of the Moslem League. Indeed, he stood head and shoulders above them and had, therefore, become the indispensable leader. From public platforms, he confessed his great dissatisfaction with the opportunism, and sometimes even worse failings, of his colleagues." Pandit Nehru concludes: "And yet some destiny or course of events had thrown him among the very people for whom he had no respect. He was their leader, but he could only keep them together by becoming himself a prisoner to their reactionary ideologies."

Pandit Nehru enabled a number of Muslim reactionaries himself (like the Majlis-e-Ahrar and Khilafatists) but there is some truth here which must be acknowledged. Jinnah is both the prisoner and victim of Pakistanis. The country is too far gone to realise his ideas, especially on the constitution and fundamental rights.

Make the Federal Constitutional Court or don't make it, but what is clear is that the Islamic Republic of Pakistan today does not even remotely resemble Jinnah's Pakistan, which -as future historians will bear me out- was too fine for the Philistines.