One of the most dogged issues that has confronted leaders of Pakistan and those of the Muslim community in India before partition is the Ahmadi issue. It is therefore worth our while to see how the All-India Muslim League and Mr Jinnah in particular dealt with the issue.

The issue had primarily agitated the Punjabi Muslim mind since the mid 1930s. The Ahmadi controversy in the Punjab Muslim League first arose 1936 when Indian nationalist Muslim group Majlis-e-Ahrar joined the Muslim Unity Parliamentary Board for the 1937 elections. Almost immediately, they began to pressure the League leadership to expel Ahmadis from the Muslim League. Ironically, Majlis e Ahrar was backed by Congress, and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru cited them as one of the many organizations supporting Congress over the Muslim League in his famous correspondence with Jinnah.

Majlis-e-Ahrar was founded in 1929 by the erstwhile Khilafatist Muslims on the advice of Maulana Azad. Possibly under the influence of Iqbal and Maulana Zafar Ali Khan and in response to Ahrar’s demand, the Punjab Provincial Muslim League, had introduced an oath requiring elected members (in the Punjab Assembly) to work towards declaring Ahmadis a separate community.

They evidently had also banned Ahmadis from the Punjab Provincial Muslim League. According to Sadia Saeed writing in book Politics of Desecularization, the ban was introduced without consulting the Central Muslim League. The oath and the ban seem to have been forgotten once Majlis-e-Ahrar broke away from the Parliamentary Board. No primary source evidence of the oath ever being used in any elections in Punjab exists.

Nevertheless it shows that there were elements in the Punjab Muslim League who had been willing to excommunicate the Ahmadis from the Muslim community as early as the mid 1930s. Leading amongst them of course was Maulana Zafar Ali Khan who was noted for his anti Ahmadi views. Dr. Ayesha Jalal writes in her book Self and Sovereignty: “In August 1936, the Ahrars officially broke with the League’s parliamentary board. The ostensible reason was their refusal to pay the stipulated sum of money to cover election expenses. But the more controversial demand, and one Jinnah wisely resisted, was that the provincial assembly candidates taking the League oath should vow to expel the Ahmadis from the Muslim community. A courageous stand to have taken, it reflects Jinnah’s understanding of constitutional law and the imperatives of citizenship in a modern state. Exclusion in any case was not going to help Muslims keep pace with, far less win, the numbers game.

Moreover, setting standards of inclusion in a community that was utterly disjointed in the legal and political sense amounted to suicide. If Jinnah had been a Punjabi, he might conceivably have taken a different position. That he was not made all the difference. He saw no reason to strip Ahmadis of their Muslim identity simply on account of a doctrinal dispute.” This antipathy for the Ahmadi community seems to have been a very specific Punjabi Muslim preoccupation, which is even true today in Pakistan.

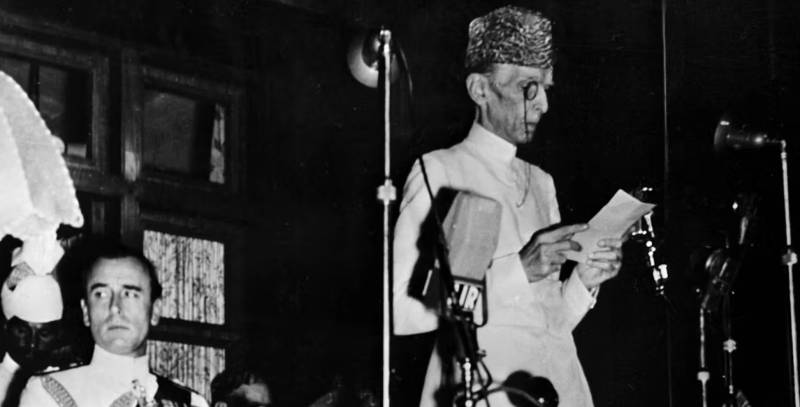

In 1939, during a speech in the Indian legislature, Jinnah praised Sir Zafrullah Khan, an Ahmadi, stating: “I wish to record my sense of appreciation – and if I say so coming from my Party – to the Honourable Sir Muhammad Zafrullah Khan, who is a Muslim and it may be said that I am flattering my own son.” This statement can be found on Page 973 of “Speeches Statements and Messages of the Quaid-e-Azam” Volume II, published by Bazm-e-Iqbal. It is interesting that Jinnah should have chosen this moment as the time to reiterate Zafrullah Khan’s Muslim identity.

In the Jinnah Papers, a letter from M.A. Hafeez Khan Farabi dated June 6, 1944, can be found. Farabi criticized Jinnah, asserting that Iqbal, who considered Ahmadis traitors, was the true architect of Pakistan. Farabi warned Jinnah that all Muslims would leave the Muslim League if Ahmadis were not expelled. Jinnah did not bother to respond.

For a few years, the Ahmadi issue receded but resurfaced in 1944. Anti-Ahmadi bodies agitated for their expulsion from the Muslim League. Jinnah’s newspapers, Dawn and Vatan, reported on May 4, 1944, that Jinnah had assured Pir Akbar Ali MLA that Ahmadis would be treated on par with other Muslim sects. Following this, Jinnah received a barrage of letters questioning this stance. To the Sunni Imam of Jama Masjid Batala, Nazir Hussain, and the Ahmadi Nazir-ul-Umoor, Jinnah cited the Muslim League’s membership clause, which stated that any Muslim resident of British India above the age of 18 could join the League.

On May 23, 1944, in Srinagar, Jinnah was asked about the status of “Qadianis,” who had been banned from Kashmir’s Muslim Conference. He replied that any Muslim could join the Muslim League without regard to sect or creed and urged the Muslims of Kashmir to avoid sectarian issues. When pressed further, Jinnah is said to have famously responded: “Who am I to declare a person non-Muslim who calls himself a Muslim.” Consequently, the Muslim Conference of Kashmir opened its doors to Ahmadis.

In the Jinnah Papers, a letter from M.A. Hafeez Khan Farabi dated June 6, 1944, can be found. Farabi criticized Jinnah, asserting that Iqbal, who considered Ahmadis traitors, was the true architect of Pakistan. Farabi warned Jinnah that all Muslims would leave the Muslim League if Ahmadis were not expelled. Jinnah did not bother to respond. In July 1944, Jinnah scuttled a resolution by Abdul Hamid Badayuni calling for the declaration of Ahmadis as non-Muslim. For a notice of resolution by Maulana Abdul Hamid Badayuni, see agenda for central council meeting dated 30 July 1944.

In his witness statement before the Munir Inquiry Commission, Mumtaz Daultana refers to this saying that it was only Jinnah’s own personal prestige that had stopped the issue from being decided then and there. See page 6 of the Witness Statement of Mumtaz Daultana. In November 1944, Majlis-e-Ahrar offered to support the Muslim League provided Jinnah denounced the "Mirzais", but Jinnah refused. Under pressure from Ahrar as well as from members of the Punjab Muslim League to declare Ahmadis non-Muslim, Jinnah, nevertheless, held his ground and refused to get involved in the dispute. Rafique Afzal in his book A History of All India Muslim League on Page 293 writes: “The issue was then transformed into a demand for the declaration of Ahmadis as Non Muslim and the Ahrar pressed the League to propose legislation on this issue.”

On 31st May 1945 the Ahrar General Secretary wrote to Muslim League general secretary calling upon Jinnah, Liaquat, MA Kazmi, Zafar Ali Khan, Abdul Ghani and Ghulam Bhik Nairang to introduce a bill in the central assembly to declare Ahmadis a Non-Muslim community. Rafique Afzal continues on Page 293 “Jinnah avoided being dragged into a divisive religious issue. The pressure in this regard increased during the general elections but then Maulana Shabbir Ahmad Usmani at one time Shaikul Hadis at Darul Ulul Deoband defended the League position in his interaction with the Ulama. Now the Ahmadis began to enrol themselves individually as members and the spiritual head of the Ahmadis was ready to extend support to the All India Muslim League on different issues.”

Here it is useful to revisit Shaukat Hayat’s testimony. Shaukat Hayat was Jinnah’s main lieutenant in Punjab. He writes in his book “The Nation that lost its soul”:

“One day I got a message from Quaid-i-Azam saying ‘Shaukat I believe you are going to Batala, which I understand is about five miles from Qadian. Please go there and meet the Hazrat sahib of Qadian request him on my behalf for his blessings and support for Pakistan’s cause. After the meeting that night at about twelve midnight, I reached Qadian. I sent him a message that I had brought a request for him from Quaid-i-Azam. He came down immediately and enquired what were Quaid’s orders. I conveyed Quaid’s message to pray for and also support Pakistan. He replied please convey to Quaid-i-Azam that we have been praying for his mission from the very beginning. Where the help of his followers is concerned, no Ahmadi will stand against a Muslim Leaguer and if someone disobeys my advice the community would not support him. So Mumtaz Daultana won overwhelming victory over the President of local Ahmadi community in Sialkot district.”

Jinnah certainly wouldn’t countenance the exclusionary path Pakistan was to travel on starting from September 1974, which has poisoned Pakistan’s polity since then. The Muslim identity he relied on during the Pakistan movement had no theocentric focus.

Given that the antipathy and outright hatred for the Ahmadi community was extremely popular amongst the Punjabi Muslims, it is all the more extraordinary that Jinnah should have chosen Zafrullah Khan to represent the Muslim League before the Boundary Commission and then as Pakistan’s first foreign minister. That Jinnah had a high regard for Zafrullah Khan’s ability as a lawyer and negotiator is obvious from Jinnah’s letter to MA Ispahani on October 22, 1947, where he writes:

“As regards Zafrullah, we do not mean that he should leave his work so long as it is necessary for him to stay there, and I think has already been informed to that effect, but naturally we are very short here of capable men, and especially of his calibre, and every now and then our eyes naturally turn to him for various problems that we have to solve.”

Some commentators have offered profane explanations for Jinnah’s choice. For example, Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed in his book on Jinnah implies that Jinnah did so because he was aware of Zafrullah Khan’s ties to Britain and the United States of America and in general of Ahmadi connections to the British government. Profane because this idea that Ahmadis were somehow the darlings of the West is a conspiracy theory that has for the most part stuck in the Punjabi Muslim mind.

In my opinion, such a public choice of a renowned Ahmadi is indicative of Jinnah’s own mind on the issue. He seems to have been unconcerned with theological disputes and controversies and that was generally reflective of his attitude towards religion.

The state’s accommodation of the Ahmadi community in 1953 when the Muslim League government refused to declare Ahmadis Non-Muslims is partly a result of this attitude. Jinnah certainly wouldn’t countenance the exclusionary path Pakistan was to travel on starting from September 1974, which has poisoned Pakistan’s polity since then. The Muslim identity he relied on during the Pakistan movement had no theocentric focus.

As I have shown above, Jinnah had resisted all attempts to force him to define the term Muslim, not just by Ahrar but also Gandhi who had pointedly asked him what he meant by “Muslims” in his correspondence. Jinnah understood that defining a Muslim would do untold harm to the political cause of the community. Congress Party’s exploitation of the Ahmadi issue as well as Shia-Sunni discord, through its allies in the Majlis-e-Ahrar, was aimed at breaking the cause of Muslim unity which was so central to the League’s mission. Most of Pakistan’s sectarian woes emanate from the country’s abandonment of this cardinal principle of League’s policy.

In 1974 Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, while certainly not a religious bigot himself, made the mistake of thinking that defining a Muslim would resolve this longstanding dispute. The 2nd Amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan, declaring Ahmadis Non-Muslims for the purposes of law and constitution, has created almost insoluble problems for the state’s religious fabric. Jinnah had once told Raja of Mahmudabad that any attempt to create an Islamic state in Pakistan would lead to dissolution of the state. Unfortunately what we see today in Pakistan is precisely that. Starting in the 1980s, the state has linked Muslim identity to a renunciation of Ahmadis. Ahmadis today constitute a very tiny minority in Pakistan, much tinier than Hindus and Christians in the country.

Once Ahmadis are decimated, which is what Pakistan’s Sunni majority is trying to do, they will be replaced by Shias and so on. The solution is to undo the 2nd Amendment and restore to Ahmadis the right to their identity as part of over all Islamicate. Unless that is done, sectarian conflict in Pakistan shall continue in perpetuity, leading quite possibly to the implosion of the state, as predicted by Jinnah himself. Only a secular Pakistan can ensure the interests of its Muslim majority and the sooner Pakistani Muslims realize that, the better it would be for them.