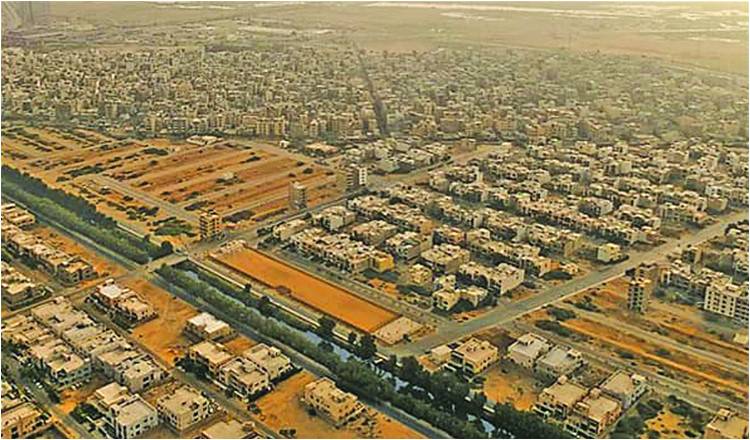

Defence Housing Authority (DHA), the country’s premier housing project, was in the news once again last week when during a hearing in Karachi, the Supreme Court took exception to its functioning and rejected a report submitted by defence secretary as “eye wash.”

Criticism of the housing project once again flashes across one’s mind with its dark images. One particularly dark image is how they are formed and how they function, as witnessed from the parliament.

How are DHAs formed? The first and the oldest DHA in Karachi was initially a private housing society formed in the 1950s. It was abolished for no lawful reason and replaced with Pakistan Defence Officers Housing Authority during General Zia’s regime under a presidential order which also imposed a management structure on the body.

Aware of the illegality of the order, Zia turned to his legal team for advice. At the time of lifting of martial law, Zia embedded the takeover order in the Constitution itself. Nothing could thus be done against the illegal takeover of a private housing society and how it was to be run since his Order Seven of 1980. Thirty years later, when in 2010 the 18th Amendment purged the Constitution of military’s intrusions, the vested interests were already too deeply entrenched.

DHAs are claimed to be private enterprises run privately without state support. But questions about how serving brigadiers, under the direct command of corps commanders, run private housing bodies have remained unanswered at best and dismissed as unpatriotic at worst.

Criticism is also blamed on ‘jealousy’ of critics. Why should anyone be ‘jealous’ if some people made good money because of the exceptional efficiency of the housing society, General Musharraf once asked while inaugurating a desalination plant in Karachi and dismissed the critics as ‘pseudo-intellectuals.’ But are such questions really motivated by jealousy?

Sometime ago the provincial government of Sindh declined to give 240 acres of land to DHA Karachi for free. It declined not due to ‘jealousy’ but because of a legislation forbidding sale of government land to other entities and also because of its high market value. However, the housing authority occupied the land. The Sindh government went in appeal before the Sindh High Court seeking a restraining order.

But soon after military’s take over in October 1999, not only were the ordinance banning the sale of land and the court petition withdrawn, the 240 acres were actually sold to DHA Karachi for a pittance of Rs20 a square yard.

The case of DHA Lahore is not too different. The Lahore Cantonment Cooperative Housing Society, a private society, was carrying out its operations on private land. As it flourished, army authorities took forcible possession of the society. The order of the Registrar Cooperative Societies to hold elections was disregarded by occupiers and allotment of plots to military officers continued.

Days before general elections on September 19, 2002 General Musharraf issued Presidential Order Number 26 setting up DHA Lahore in place of the civilian cooperative housing society. The order was subsequently indemnified through the 17th Constitutional amendment giving a pseudo-legal basis to the takeover. State power was dubiously used to advance corporate interests of the occupiers.

The DHA in Islamabad was also set up in February 2005 through an ordinance issued just on the eve of the parliament’s session during the days the military called the shots under General Musharraf.

It was claimed before the parliament that DHAs are needed to meet ‘socio economic needs of army officers.’

The parliament learnt that army officers were entitled to up to four plots: the first after 15 years of service, second after 25 years, third after 28 years and the fourth after 33 years of service. Later, it was reported that the entitlement to a fourth plot was withdrawn. Whether the withdrawal of the fourth plot was temporary or permanent is not known.

It was also learnt that retired army officers were also entitled to plots in DHA Islamabad but not retired Navy and PAF officers. A serving navy and air force officer was entitled after 25 years of service, while an army officer after 15 years of service.

The quota for all categories of civilians was never disclosed, encouraging tens of thousands of civilians to apply for plots. Hundreds of millions were collected in non-refundable registration fees from them, which then went into the DHA coffers.

In reply to a parliamentary question about the proposal to allot commercial plots to defence officers in the federal capital, the then defence minister stated that commercial plots in the federal capital would be allotted by the Defence Housing Scheme Islamabad, adding that the scheme was a project of Welfare and Rehabilitation Directorate of the GHQ.

To be honest the questions asked by the writer in the parliament were not motivated by ‘jealousy.’ To be fair, honest answers were given whether wittingly or unwittingly. Urging the DHAs now to pause and ponder over criticism is neither jealousy nor unpatriotic.

The writer is a former senator

Criticism of the housing project once again flashes across one’s mind with its dark images. One particularly dark image is how they are formed and how they function, as witnessed from the parliament.

How are DHAs formed? The first and the oldest DHA in Karachi was initially a private housing society formed in the 1950s. It was abolished for no lawful reason and replaced with Pakistan Defence Officers Housing Authority during General Zia’s regime under a presidential order which also imposed a management structure on the body.

Aware of the illegality of the order, Zia turned to his legal team for advice. At the time of lifting of martial law, Zia embedded the takeover order in the Constitution itself. Nothing could thus be done against the illegal takeover of a private housing society and how it was to be run since his Order Seven of 1980. Thirty years later, when in 2010 the 18th Amendment purged the Constitution of military’s intrusions, the vested interests were already too deeply entrenched.

Days before general elections on September 19, 2002 General Musharraf issued Presidential Order Number 26 setting up DHA Lahore in place of the civilian cooperative housing society

DHAs are claimed to be private enterprises run privately without state support. But questions about how serving brigadiers, under the direct command of corps commanders, run private housing bodies have remained unanswered at best and dismissed as unpatriotic at worst.

Criticism is also blamed on ‘jealousy’ of critics. Why should anyone be ‘jealous’ if some people made good money because of the exceptional efficiency of the housing society, General Musharraf once asked while inaugurating a desalination plant in Karachi and dismissed the critics as ‘pseudo-intellectuals.’ But are such questions really motivated by jealousy?

Sometime ago the provincial government of Sindh declined to give 240 acres of land to DHA Karachi for free. It declined not due to ‘jealousy’ but because of a legislation forbidding sale of government land to other entities and also because of its high market value. However, the housing authority occupied the land. The Sindh government went in appeal before the Sindh High Court seeking a restraining order.

But soon after military’s take over in October 1999, not only were the ordinance banning the sale of land and the court petition withdrawn, the 240 acres were actually sold to DHA Karachi for a pittance of Rs20 a square yard.

The case of DHA Lahore is not too different. The Lahore Cantonment Cooperative Housing Society, a private society, was carrying out its operations on private land. As it flourished, army authorities took forcible possession of the society. The order of the Registrar Cooperative Societies to hold elections was disregarded by occupiers and allotment of plots to military officers continued.

Days before general elections on September 19, 2002 General Musharraf issued Presidential Order Number 26 setting up DHA Lahore in place of the civilian cooperative housing society. The order was subsequently indemnified through the 17th Constitutional amendment giving a pseudo-legal basis to the takeover. State power was dubiously used to advance corporate interests of the occupiers.

The DHA in Islamabad was also set up in February 2005 through an ordinance issued just on the eve of the parliament’s session during the days the military called the shots under General Musharraf.

It was claimed before the parliament that DHAs are needed to meet ‘socio economic needs of army officers.’

The parliament learnt that army officers were entitled to up to four plots: the first after 15 years of service, second after 25 years, third after 28 years and the fourth after 33 years of service. Later, it was reported that the entitlement to a fourth plot was withdrawn. Whether the withdrawal of the fourth plot was temporary or permanent is not known.

It was also learnt that retired army officers were also entitled to plots in DHA Islamabad but not retired Navy and PAF officers. A serving navy and air force officer was entitled after 25 years of service, while an army officer after 15 years of service.

The quota for all categories of civilians was never disclosed, encouraging tens of thousands of civilians to apply for plots. Hundreds of millions were collected in non-refundable registration fees from them, which then went into the DHA coffers.

In reply to a parliamentary question about the proposal to allot commercial plots to defence officers in the federal capital, the then defence minister stated that commercial plots in the federal capital would be allotted by the Defence Housing Scheme Islamabad, adding that the scheme was a project of Welfare and Rehabilitation Directorate of the GHQ.

To be honest the questions asked by the writer in the parliament were not motivated by ‘jealousy.’ To be fair, honest answers were given whether wittingly or unwittingly. Urging the DHAs now to pause and ponder over criticism is neither jealousy nor unpatriotic.

The writer is a former senator