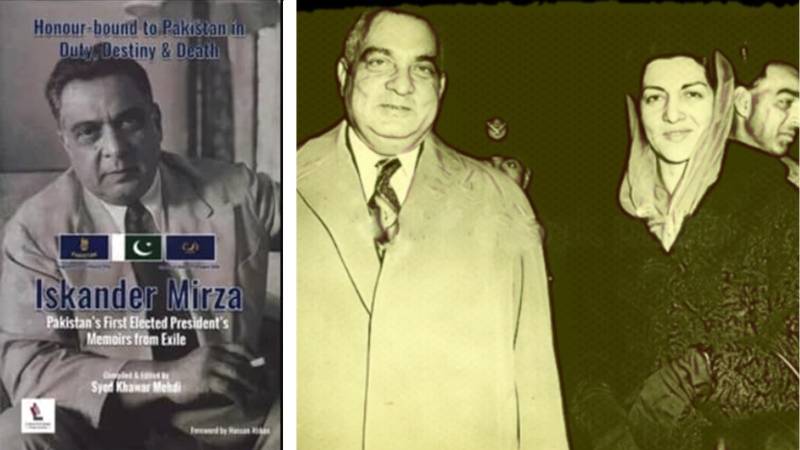

A recent book compiled and edited by Syed Khawar Mehdi, Iskander Mirza: Pakistan’s First Elected President’s Memoirs from Exile (Lightstone publishers, 2023), makes ample and unambiguous revelations about Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s determination to achieve Pakistan at all costs, including if it led to large-scale communal violence.

Iskander Mirza, it may be noted, first joined the army but later started working in the Political Service. The Political Service kept an eye on tribal areas to ensure that British interests were safeguarded in them. He had been serving in the tribal areas of the NWFP (today Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa) where he wielded considerable influence.

On pages 95-96, Mehdi narrates that in February 1947 Jinnah summoned Iskander Mirza and asked him point-blank if he considered him the supreme leader of Muslims and would do whatever Jinnah told him was imperative to achieve Pakistan. Mirza conceded that he did, and would follow his orders:

“He went on to say that he was afraid he was not going to get Pakistan, unless some serious trouble was created and the best place to do this was on the North-Western Frontier with the tribes. […] If Pakistan was not conceded by negotiations, we must fight […] by the middle of May, he wanted me to resign from the service, go into tribal territory and start a Jehad […] His request took my breath away. My associations with the British were of long standing […] With Hindus too my relations were excellent and I had some good friends among them.”

Mirza then goes on to say that implementing such instructions would mean “raids on border villages in the settled areas in which quite a few Hindus would be killed.” However, he decided to “fall in line with the Quaid-e-Azam’s plan” (page 96). Jinnah assured him that if anything happened to him he would look after his family!

Since communal violence had now broken out and the British had come around to the creation of Pakistan, Jinnah told Iskander Mirza in May 1947 that there was no longer any need to create trouble in the tribal areas

Mirza told him that to foment communal violence in Waziristan, Tirah and Momand agencies, he would need one crore (10 million) rupees. Jinnah had already taken care of it. The cover for the transfer of money was to be the Khan of Kalat, but the money was to be provided by the Nawab of Bhopal. Mirza says that he met the Nawab of Bhopal the same day and was paid an initial Rs 20,000 to start the trouble (page 96).

It can be mentioned that the Jinnah-Iskander meeting took place in February. However, in March 1947 Jinnah’s strategy to use communal violence was already in operation after his call for direct action in Punjab brought down the elected coalition government of Sir Khizr Hayat Khan Tiwana, which included the Punjab Unionist Party, the Punjab Congress and the Sikh Panthic Parties. The violence which ensued and became endemic unnerved the Congress leaders as well as the British, who were still working to keep India loosely united but bound to the British Commonwealth through a defence treaty.

By May 1947, British policy changed significantly in favour of Pakistan. I have shown in my books Pakistan the Garrison State and Jinnah: His Successes, Failures and Role in History that on 12 May 1947, the British military and top officials from the Colonial Office had come around to the idea of Pakistan and supported the Partition on grounds that while Jinnah had shown an interest in joining the Commonwealth, Hindustan may decide to reman sovereign and independent. In the end, Mountbatten was able to cajole even Nehru and the Congress left-wing to opt for joining the Commonwealth – otherwise the British would be treaty-bound to support Pakistan (as a member of the Commonwealth) in a war with India.

Since communal violence had now broken out and the British had come around to the creation of Pakistan, Jinnah told Iskander Mirza in May 1947 that there was no longer any need to create trouble in the tribal areas.

It is important to underscore that as early as 29 July 1946, Jinnah had issued a dire threat to use violence after Nehru had on 10 July 1946 said that the Congress Party would go to the Constituent Assembly, which the 16 May 1946 Cabinet Mission had prescribed, to frame a constitution for a united India free from all fetters. Jinnah had said:

“Never have we in the whole history of the League done anything, except by constitutional methods and by constitutionalism. But now we are obliged and forced into this position. This day we bid good-bye to constitutional methods.

Throughout the fateful negotiations […] the British and the Congress, held a pistol in their hand, the one of authority and the other of mass struggle and non-cooperation. Today, we have forced a pistol and are in a position to use it […] We mean it […] every word of it. We do not believe in equivocation.”

On 16 August 1946, all hell broke loose in Calcutta, which at that time had a Muslim League Government in office headed by Hussain Shaheed Suhrawardy. Anywhere between 4,000 to 10,000 Hindus and Muslims were killed in a matter of four days. The Great Calcutta Killing set in motion recurring communal violence which engulfed many parts of the Subcontinent, especially the Punjab, leaving at least one million Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs killed. Another 12 to 15 million fled their homes, mostly to escape injury and death, by the time the fate year of 1947 ended.

It must be noted that Jinnah or the Muslim League in general were never charged with instigation to violence although the Congress leaders were sent to jail repeatedly even for non-violent resistance to British rule. The only reason this discriminatory policy was followed must be because neither Jinnah nor the Muslim League resisted British rule peacefully or through violent means.

Iskander Mirza also reveals that Jinnah angered the visiting Afghan king Shah Mahmood Khan by refusing to meet him at Mountbatten’s lunch invitation, saying that if the king wanted to meet him, he could call upon him in his home. Also, Mirza tells us that when he told Jinnah to be considerate to Muslim Leaguers because they brought Pakistan into being Jinnah retorted: “Who told you the Muslim League brought in Pakistan? I brought in Pakistan – with my stenographer” (page 97).

It is no wonder Pakistan could never develop a democratic identity or culture because the founder of the nation claimed all honours for himself demeaning his peers and disciples.