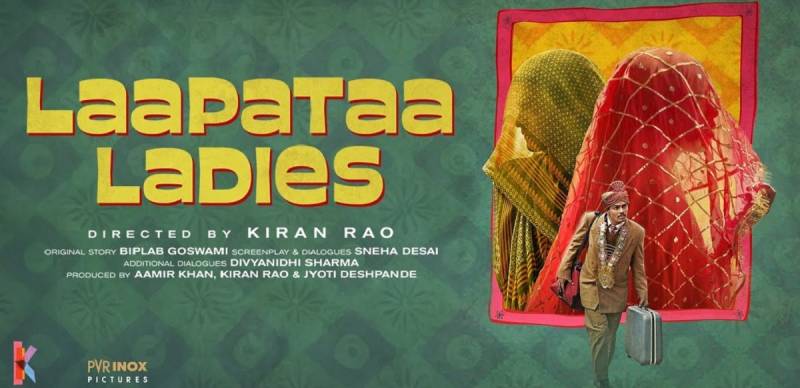

Kiran Rao's 2023 Netflix comedy-drama Laapataa Ladies is not your average fare from Bollywood. Underneath its highly embellished wedding dresses lies a complex and wholly Eastern exploration of relationships that women form in this part of the world of identity, societal expectations, societal standards of honour and women's empowerment.

Rao has approached Laapataa Ladies with love and a back-to-basics simplicity. It is a story by Biplab Goswami, with a screenplay and dialogue by Sneha Desai and Divyanidhi Sharma. The film delicately follows the journey of Jaya and Phool as they navigate the unpredictable and unknown elements of life outside of their homes.

The movie is set in fictional villages in North India. Jaya and Phool are travelling to their respective in-law's homes with their husbands. Both brides wear identical wedding clothes with long, red veils that make it impossible to distinguish who is who. This leads to the central conflict in the story as the young brides get swapped by an honest mistake late at night in a dark train cabin. This mix-up sets the stage for convoluted but sweet chaos as the events unfold from the perspectives of the two lost brides.

It is the practical inconvenience of the ghoonghat, which is otherwise meant to conceal the women from the outside world and direct their gaze downwards, that opens their eyes to a different world

Phool is the more innocent of the two and finds herself stranded at a far-off train station, unable to contact her family or husband because she never learned the name of her husband's village. She lived a life of complete resignation in her parents' home, always prepared to marry, transitioning from the role of daughter to the role of a wife and a daughter-in-law. Fortunately, the kind tea stall owner and the gang of misfits at the railway station take her under their wing, and through them, Phool is introduced to a different world.

On the other hand, Jaya is mistakenly taken away by Phool's husband, Deepak. She uses a fake name, Pushpa, to hide her true identity. The "fake bride gang" news story is also planted early to create an air of mystery and doubts about Jaya's moral legitimacy. Initially, her actions depict an ulterior agenda. However, once the film reveals her quest for independence, education and agency, we understand that the shroud of conspiracies and deception is to expose the society that views all women who dare to dream as villainous.

After watching the film and reading its reviews, I felt that the one aspect of the film that has been overlooked is the complexity around the concept of the veil. Feminists and liberals predominantly consider veils as a form of oppression, and several European countries, such as France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Denmark, have outlawed it, citing reasons such as secularism, social cohesion among immigrants, gender equality, openness in communication, and public safety. However, this movie approaches the issue of the ghoonghat (veil) not from the perspective of an external observer but from the viewpoint of those who are required to wear it. It is the practical inconvenience of the ghoonghat, which is otherwise meant to conceal the women from the outside world and direct their gaze downwards, that opens their eyes to a different world.

As for Phool, the ghoonghat caused the most significant accident of her life - getting lost and eventually finding herself as a woman, separate from the labels of 'wife' or daughter. It is her journey of self-actualisation, and the film conveys that empowerment can also mean learning to be an individual on your own without escaping the shackles of marriage. For the other bride, Jaya, the ghoonghat blesses her with an opportunity to exercise her agency. Jaya was forcibly married by her parents to a widower whose wife died under suspicious circumstances, implied to be the victim of domestic violence. She wanted to study agriculture and modern farming practices. After the swap, she seizes the chance to escape her forced marriage and pursue her education. She is smart enough to know that if her true identity is revealed, she would quickly be found through the corresponding missing brides' FIRs filed by Phool's husband and her own.

The movie beautifully contrasts these two perspectives. Phool's husband, desperate to find his wife, shows the police inspector their wedding picture, in which Phool is veiled. Sadly, he has no other photo to identify her. The inspector, portrayed brilliantly by Ravi Kishan, sarcastically quips, "Buhat sundar hai" (she is very beautiful) upon seeing the veiled picture. In contrast, when the inspector is informed of a similar missing bride case from a nearby village, he asks Jaya to have her picture taken for identification. However, Jaya cleverly uses the ghoonghat and the modesty associated with it to hide her face from the investigation.

Manju exposes the 'big fraud' happening with girls in the name of respect and honour for centuries; women are made to believe that their virtue and value lie in their complete self-effacement and absolute subjugation required for the perpetuation of patriarchal values

The role of the old independent woman, Manju, serves as a powerful commentary on the issues of patriarchy, poverty, choice and love – themes which are intricately woven throughout the movie's plot. Manju's sharp outbursts and stern demeanour hide a broken, oppressive past, a life full of struggles. She jolts Phool out of the ideals of respect, honour and uprightness ingrained in her through her upbringing that limit her existence as a woman. When Phool is naively bragging about her good upbringing, which forbids her from going back to her parent's home without her husband and is unable to recall the name of her husband's village, Manju lashes out at her. She exposes the 'big fraud' happening with girls in the name of respect and honour for centuries; women are made to believe that their virtue and value lies in their complete self-effacement and absolute subjugation required for the perpetuation of patriarchal values.

To teach her a lesson about her false pride and ignorance, Manju refuses to shelter Phool and retorts: "There's nothing shameful in being a fool, but feeling proud of being a fool is shameful". She teaches Phool how to survive on her own and build relationships based on mutual respect. When Phool asks why Manju lives alone, Manju reveals that both her husband and son relied on her earnings but would beat her after getting drunk, justifying their actions in the name of "love". She then sarcastically reveals that one day, she exercised her own "right of love", implying that she fought back. Her cynicism softens towards the end, realising that rebellion need not exclude the right to love.

The movie's characterisation masterfully captures the complexities of human nature as it is shaped by society. Jaya's husband, Pradeep, is depicted as a true embodiment of the exploitative, patriarchal mindset. He immediately assumes that his missing wife has eloped, showing little concern for her safety or well-being. Instead of searching for her, he is frustrated by the disruption of his wedding night and seeks paid sex as a way to compensate for his unmet expectations. His demeanour is vile and threatening.

In contrast, the world of Deepak, Phool's husband, falls apart. He is concerned for Phool's safety and leaves no stone unturned for his wife's return. At the same time, he is concerned for Jaya and reassures her safe return to her family. Unlike Pradeep, Deepak lacks influence with the police or the government. When he discovers Jaya's lie, he shows compassion despite the fact that her deception may have hindered and delayed the search for his wife.

Manohar emerges as an anti-villain when, in the end, he defends Jaya against her abusive husband and allows her to leave with all her dowry jewellery to pursue her education - the most crowd-pleasing transformation

The pan-chewing police inspector, Shyam Manohar, is a typical representation of a law enforcement officer in a hierarchical Indian society who exploits the vulnerabilities of ordinary people for his own petty gains through bribery or abuse of authority. His character is depicted as selfish, ruthless, and lacking empathy. However, the film refuses to confine him to the stereotype of the corrupt, villainous Bollywood cop. Instead, Manohar emerges as an anti-villain when, in the end, he defends Jaya against her abusive husband and allows her to leave with all her dowry jewellery to pursue her education - the most crowd-pleasing transformation.

The film also explores the rich, meaningful bonds among women who support one another in a dehumanising patriarchal culture. Jaya forms a strong and warm connection with Phool's sister-in-law – Poonam – (Deepka's brother's wife), showcasing the strength of female solidarity. Jaya inspires her to speak, smile and express her artistic talents. Observing the close bond between Jaya and her daughter-in-law, Phool's mother-in-law playfully proposes friendship to her own mother-in-law, with whom she continues to encounter and manage ongoing struggles over boundaries and territory.

My only reservation is that, despite the film's strong plot, well-developed characters, and sharp wit and dialogue, it occasionally resorts to unnecessary reinforcement of its main themes. This introduces a caricature-like quality, which, rather than adding humour, undermines the otherwise impactful commentary on serious issues. When Phool is lost at the railway station, she hides behind the dumpster that is labelled 'use me'. It appears to be a distasteful and flagrant reference to the social perception of an unchaperoned woman. Similarly, Bablu, Poonam's son, compares women to 'lost shoes' outside temples, which are claimed by whoever finds them, and suggests that the same should apply to women, implying that Jaya should become his aunt. In a film so beautifully crafted with layers of meaning, such instances of overt symbolism feel unnecessary.

Notwithstanding these minor excesses, the film is undoubtedly an honest and detailed work which has achieved big success despite its reportedly meagre budget of ₹40−50 million. There are no special effects, action sequences, or popular names. It did not compromise on the story or production quality. The fictional state of Nirmal Pradesh and its residents possess cultural authenticity. The film's strength comes from ironic comedy, the complexity of its characters and the actors' performances.