Pakistan’s internationally acclaimed, self-taught anamorphic street artist, Obaid ur Rahman, was recently in Germany, where he was invited as one of 45 participants to show his work in the Wilhemshaven International Street Festival.

“It was such an honour for me to represent Pakistan at an event where no Pakistani has participated before,” he says enthusiastically. “It was an amazing opportunity to project a positive image of Pakistan internationally. Everything I have is because of Pakistan, so it was a very proud moment for me. And it was an overwhelming experience, working alongside my idols... Seeing their work in person and getting to know about their processes was amazing.”

He started practising this form of art two years ago, taking a break from art school and initially drawing with pieces of coal on the roof of his building. He experimented with various types of composition, from simple cartoon characters to pool drawings and complex pieces. Then in December 2014, the Dolmen Mall in Karachi allowed him to create a drawing on their premises. So with coloured chalk, he produced a piece showing an irregularly shaped blue pool with a great-toothed shark rising out of it. This was well received by the public and gave him extra motivation to carry on with 3D/anamorphic art, which is not widely known in Pakistan and is hardly ever seen in galleries.

Anamorphic art was born in the early Renaissance. It obeys all the laws of perspective, but is an extreme form of this, in that an anamorphic picture is usually distorted in some way, but appears normal when viewed from a particular perspective. A notable and much acclaimed early example of anamorphosis is seen in ‘The Ambassadors,’ by German-Swiss 20th-century portrait artist Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543), who painted in the Northern Renaissance style. By the turn of the 20th century however, on the world stage, street art had begun to evolve into complex, interdisciplinary forms of artistic expression. So now we see graffiti, stencils, murals, prints – from large-scale paintings and projects of artistic collaboration to street installations, performative and video art. One could say that street art has found its way into the core of contemporary art, into the galleries and the global art market, whereas formerly it was essentially illegal, a process of creation through destruction, and a way for the young to respond to their socio-political environment, taking the battle for meaning into their own hands.

Chalk drawings themselves have been known since prehistoric times, but the medium really came into its own in the late 15th century, especially in the hands of Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael and even Rembrandt, who used it to make preliminary sketches of their works. Later artists like Degas, Matisse and Picasso also used it, to sketch or add effects to their compositions.

And street art is thought to have originated in 16th-century Italy, amongst the Madonnari, who were vagabond artists, visual counterparts of the minstrels. They painted religious pictures – particularly of the Madonna – directly onto the beaten earth, or on paved public squares, using chalk, brick, charcoal and coloured stones. Their work is tied to a rich history of Italian religious art, and is connected, for example, to icons and offerings given in gratitude for a prayer answered. A small number of such artists continued right up to the 1980s. At the International Street Painting Festival in Grazie di Curtatone, northern Italy, they received recognition for their efforts, and also witnessed the transformation of their art into a worldwide phenomenon.

As to Obaid’s pictures, his pavement exhibit in Germany was a stylised and very large 3D presentation of a female musician from the Indian subcontinent, playing a two-stringed instrument. He first sketched the outline in yellow chalk, then filled in the beautiful colours and the details of her costume and jewellery – watched by a fascinated audience.

At his recent exhibition of six large format pictures at Sanat Gallery, Karachi, he presented a fascinating variety of subjects, from teddy bear to tiger. He was busy creating his pictures in the gallery for almost a month, during which time he welcomed visitors wishing to see the process and to converse with him. He transformed the walls and floor with his colourful compositions, and one could say that by entering through a portal, his viewers had already entered the world of Alice in Wonderland, though of course not in the same manner.

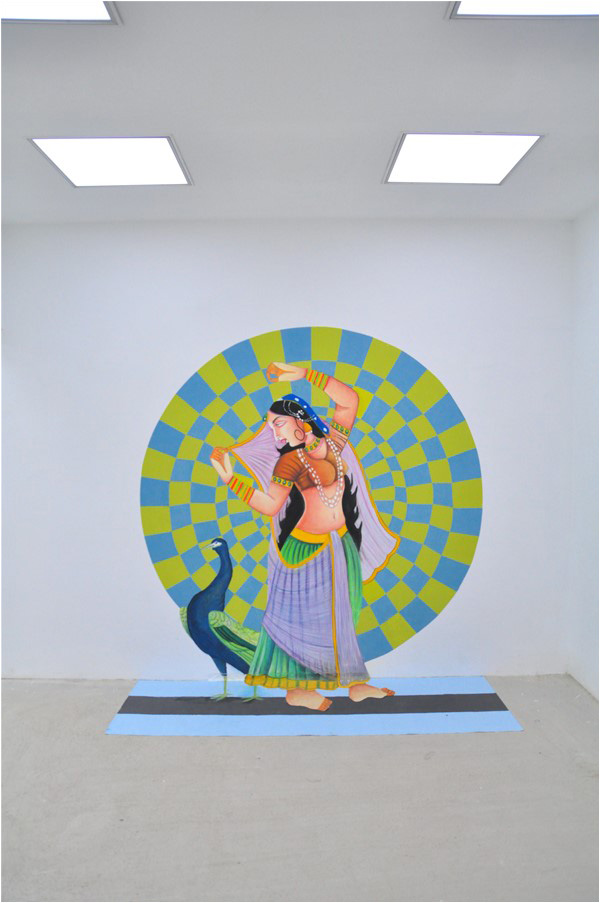

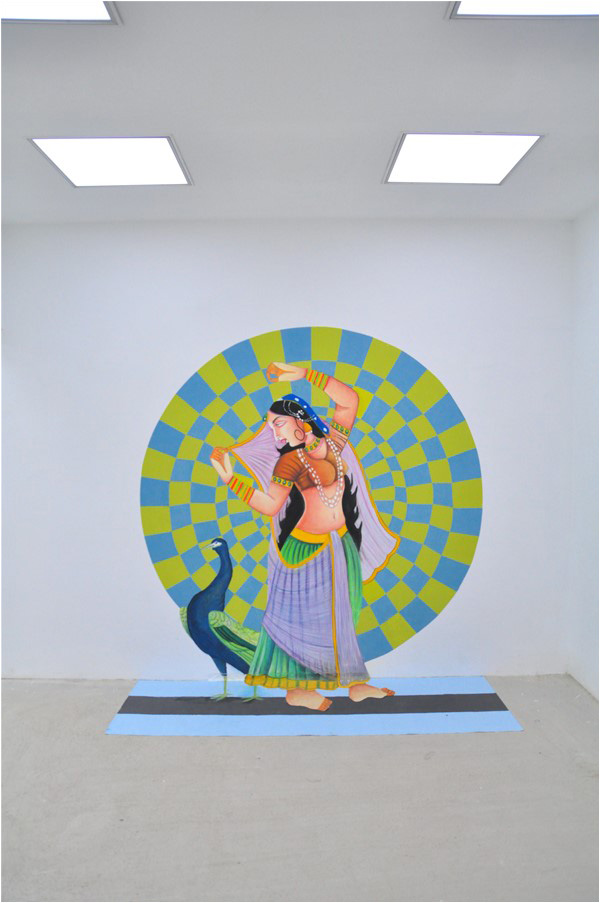

One of his wall exhibits was a Mughal-style dancer in the miniature style, and the artist has cleverly placed her feet on the gallery floor. So although this exhibition is described as ‘a journey to Wonderland’ – rather different from what Alice saw – one can say that the dancer ‘has her feet on the ground.’ The curving lines of her graceful pose contrast tastefully with the checked background, while the peacock beside her adds his elegance to the picture, though his famous tail is not visible. Perhaps it would have detracted from the clear lines of the picture.

As to the teddy bear, much to his annoyance Theodore Roosevelt, who served as U.S. President from 1901 to 1909, was commonly known as Teddy. He enjoyed bear-hunting, and the story goes that on one such hunt, he refused to shoot as sport an old and injured bear, though he ordered it to be put down to end its misery. This was widely reported in newspapers, and a cartoonist hopped on the bandwagon, too. But the teddy bear link came when, not to be outdone, a confectioner placed two homemade, stuffed toy bears in his display window, and with presidential permission labeled them ‘Teddy’s Bears.’ Obaid’s large teddy bear image, which covers a corner of the gallery, is partly hidden by the faux walls and passages. In front of him is the entry to a passage via a multicoloured portal – doorway to Wonderland? – while a striped wall to the left keeps him in his place. For many of us, considering the teddy bears we played with as children, this is a somewhat nostalgic picture. And it reminds me of the huge, deep-growling teddy bear that my mother brought from England as a child.

A big attraction in Obaid’s show was the centre-stage swimming pool, which like a mirage had viewers at first believing that it really contained water. People were seen dangling their feet above it, and enacting theatrical scenes around it. The artist has obviously observed water carefully, letting it reflect on the upper walls of the pool, and showing a hint of movement. This is a form of interactive art, not witnessed along with other art forms, and Obaid was naturally happy to see the viewers’ actual physical involvement. But it brings to mind a remark by scuptor Amin Gulgee, who said, “I love my work to be touched.” This too is a form of interaction, though not as obvious as that observed in Sanat Gallery.

With its shadow clearly etched upon the wall, a lifelike but not ferocious tiger steps daintily out of his irregularly shaped frame of foliage, apparently on an inspection tour if one considers the angle of his head. This is a very carefully drawn piece, with much attention paid to the characteristics of the feline genus. Meanwhile, the stylised mountains behind the tiger add colour contrast and depth of field to the composition.

Nearby one sees a geometric composition, something completely different in character from the rest of the exhibition, and presented in rani pink and turquoise, with a subtle degree of colour variation. Up to a point it resembles a maze, but without the entry and exit points common to these marvels of imagination. Actually, the maze is one of the oldest symbols of humanity, dating back at least to 2500 BC, and found, with various meanings, in most cultures.

This was Obaid’s first show in a gallery, and perhaps it is also the first time a gallery in Pakistan has displayed 3-dimensional illusionary compositions. It will be interesting not only to follow this young artist’s career, but to see how his chosen mode of expression develops in this country.

“It was such an honour for me to represent Pakistan at an event where no Pakistani has participated before,” he says enthusiastically. “It was an amazing opportunity to project a positive image of Pakistan internationally. Everything I have is because of Pakistan, so it was a very proud moment for me. And it was an overwhelming experience, working alongside my idols... Seeing their work in person and getting to know about their processes was amazing.”

He started practising this form of art two years ago, taking a break from art school and initially drawing with pieces of coal on the roof of his building. He experimented with various types of composition, from simple cartoon characters to pool drawings and complex pieces. Then in December 2014, the Dolmen Mall in Karachi allowed him to create a drawing on their premises. So with coloured chalk, he produced a piece showing an irregularly shaped blue pool with a great-toothed shark rising out of it. This was well received by the public and gave him extra motivation to carry on with 3D/anamorphic art, which is not widely known in Pakistan and is hardly ever seen in galleries.

Anamorphic art was born in the early Renaissance. It obeys all the laws of perspective, but is an extreme form of this, in that an anamorphic picture is usually distorted in some way, but appears normal when viewed from a particular perspective. A notable and much acclaimed early example of anamorphosis is seen in ‘The Ambassadors,’ by German-Swiss 20th-century portrait artist Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543), who painted in the Northern Renaissance style. By the turn of the 20th century however, on the world stage, street art had begun to evolve into complex, interdisciplinary forms of artistic expression. So now we see graffiti, stencils, murals, prints – from large-scale paintings and projects of artistic collaboration to street installations, performative and video art. One could say that street art has found its way into the core of contemporary art, into the galleries and the global art market, whereas formerly it was essentially illegal, a process of creation through destruction, and a way for the young to respond to their socio-political environment, taking the battle for meaning into their own hands.

Chalk drawings themselves have been known since prehistoric times, but the medium really came into its own in the late 15th century, especially in the hands of Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael and even Rembrandt, who used it to make preliminary sketches of their works. Later artists like Degas, Matisse and Picasso also used it, to sketch or add effects to their compositions.

And street art is thought to have originated in 16th-century Italy, amongst the Madonnari, who were vagabond artists, visual counterparts of the minstrels. They painted religious pictures – particularly of the Madonna – directly onto the beaten earth, or on paved public squares, using chalk, brick, charcoal and coloured stones. Their work is tied to a rich history of Italian religious art, and is connected, for example, to icons and offerings given in gratitude for a prayer answered. A small number of such artists continued right up to the 1980s. At the International Street Painting Festival in Grazie di Curtatone, northern Italy, they received recognition for their efforts, and also witnessed the transformation of their art into a worldwide phenomenon.

As to Obaid’s pictures, his pavement exhibit in Germany was a stylised and very large 3D presentation of a female musician from the Indian subcontinent, playing a two-stringed instrument. He first sketched the outline in yellow chalk, then filled in the beautiful colours and the details of her costume and jewellery – watched by a fascinated audience.

At his recent exhibition of six large format pictures at Sanat Gallery, Karachi, he presented a fascinating variety of subjects, from teddy bear to tiger. He was busy creating his pictures in the gallery for almost a month, during which time he welcomed visitors wishing to see the process and to converse with him. He transformed the walls and floor with his colourful compositions, and one could say that by entering through a portal, his viewers had already entered the world of Alice in Wonderland, though of course not in the same manner.

One of his wall exhibits was a Mughal-style dancer in the miniature style, and the artist has cleverly placed her feet on the gallery floor. So although this exhibition is described as ‘a journey to Wonderland’ – rather different from what Alice saw – one can say that the dancer ‘has her feet on the ground.’ The curving lines of her graceful pose contrast tastefully with the checked background, while the peacock beside her adds his elegance to the picture, though his famous tail is not visible. Perhaps it would have detracted from the clear lines of the picture.

He first sketched the outline in yellow chalk, then filled in the beautiful colours and the details of her costume and jewellery, watched by a fascinated audience

As to the teddy bear, much to his annoyance Theodore Roosevelt, who served as U.S. President from 1901 to 1909, was commonly known as Teddy. He enjoyed bear-hunting, and the story goes that on one such hunt, he refused to shoot as sport an old and injured bear, though he ordered it to be put down to end its misery. This was widely reported in newspapers, and a cartoonist hopped on the bandwagon, too. But the teddy bear link came when, not to be outdone, a confectioner placed two homemade, stuffed toy bears in his display window, and with presidential permission labeled them ‘Teddy’s Bears.’ Obaid’s large teddy bear image, which covers a corner of the gallery, is partly hidden by the faux walls and passages. In front of him is the entry to a passage via a multicoloured portal – doorway to Wonderland? – while a striped wall to the left keeps him in his place. For many of us, considering the teddy bears we played with as children, this is a somewhat nostalgic picture. And it reminds me of the huge, deep-growling teddy bear that my mother brought from England as a child.

A big attraction in Obaid’s show was the centre-stage swimming pool, which like a mirage had viewers at first believing that it really contained water. People were seen dangling their feet above it, and enacting theatrical scenes around it. The artist has obviously observed water carefully, letting it reflect on the upper walls of the pool, and showing a hint of movement. This is a form of interactive art, not witnessed along with other art forms, and Obaid was naturally happy to see the viewers’ actual physical involvement. But it brings to mind a remark by scuptor Amin Gulgee, who said, “I love my work to be touched.” This too is a form of interaction, though not as obvious as that observed in Sanat Gallery.

With its shadow clearly etched upon the wall, a lifelike but not ferocious tiger steps daintily out of his irregularly shaped frame of foliage, apparently on an inspection tour if one considers the angle of his head. This is a very carefully drawn piece, with much attention paid to the characteristics of the feline genus. Meanwhile, the stylised mountains behind the tiger add colour contrast and depth of field to the composition.

Nearby one sees a geometric composition, something completely different in character from the rest of the exhibition, and presented in rani pink and turquoise, with a subtle degree of colour variation. Up to a point it resembles a maze, but without the entry and exit points common to these marvels of imagination. Actually, the maze is one of the oldest symbols of humanity, dating back at least to 2500 BC, and found, with various meanings, in most cultures.

This was Obaid’s first show in a gallery, and perhaps it is also the first time a gallery in Pakistan has displayed 3-dimensional illusionary compositions. It will be interesting not only to follow this young artist’s career, but to see how his chosen mode of expression develops in this country.