The earlier British period in India was an era of newness, excitement, and discovery for colonial officials and scholars. They immersed themselves in studying local languages, literature, religion, rituals and social fabric. On the other hand, British reform programs supported enculturation and interaction among various religions and cultures. Prominent city-centres such as Calcutta (now Kolkata), Hyderabad (Sindh), Bombay (now Mumbai), Karachi, Chennai, Lahore, Delhi and Kanpur were hubs of social-amalgamation. Locals’ exposure to Western cultures, modern educational systems and advanced technologies helped them to think anew and question their traditional cultures.

We may say that Raja Rammohun Roy's (1772-1833) Brahmo Samaj was an outcome of that ‘acculturation.’ Therefore, it was an organisation that promoted a new cultural movement in India, particularly in Bengal – as it was the first region that encountered Western forms of thought, organisations and formal structures.

Without a doubt, Roy was a product of diverse cultural influences and had a varied career, including work in private banking and the East India Company. He turned his attention to social customs and religious beliefs, particularly the issue of Sati (the immolation of Hindu widows). The Brahmo Samaj evolved over time, with a younger generation of Bengalis, led by Keshab Chandra Sen, who introduced some radical changes in the society: not worshipping any type of idols, promotion of girls’ education, English schooling and even inter-caste marriages. This led to a division within the Samaj, with the more conservative Adi Brahmo Samaj under Debendranath Tagore and the Brahmo Samaj of India led by Sen.

The Brahmo Samaj expanded throughout the Subcontinent during the 1860s and 1870s, attracting young Bengalis from the villages and towns of eastern Bengal. By 1872, Keshab Chandra Sen’s Brahmo Samaj organisation had expanded throughout much of the Indian subcontinent. Branches of the Samaj extended through Bihar, the United Provinces, and reached as far as the Punjab, Assam, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, and Sindh (Hyderabad). This expansion reflected the appeal of the Brahmo Samaj’s reformist agenda.

In fact, in Sindh, Navalrai, a young Amil from Hyderabad and the son of the Diwan of Shaukiran (Mukhi of Hyderabad's Amil Community), was the first one who responded to the call of Keshab Chandra Sen, although his family was followers of Guru Nanak. He was the first to create ripples of a new thought among the residents of the sleepy Hyderabad.

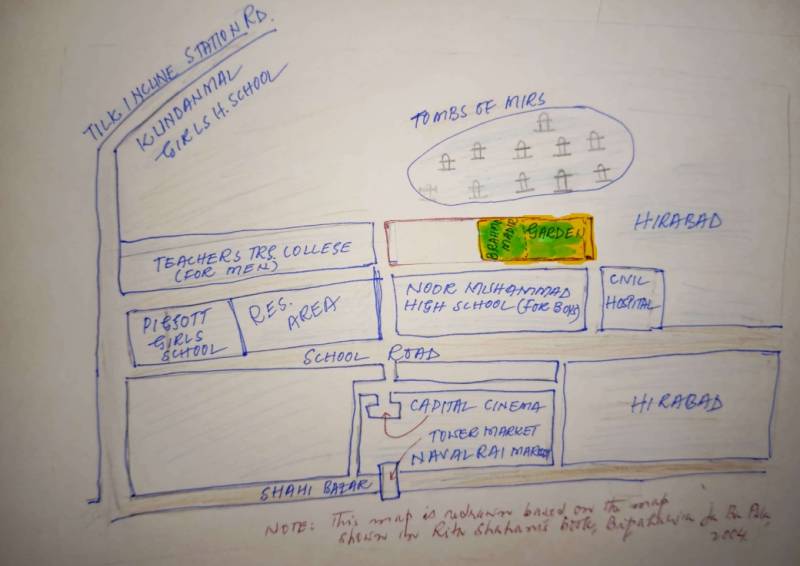

The Brahmo Mandir had a garden, and at the centre stood a robust Banyan tree, with an elevated platform around its huge trunk. There were also some younger Banyan trees and other plants. One of the regular activities that occurred was meditation

There is a need for more exploration to learn about Navalrai’s positive response to Keshab Chandra Sen's call. However, until now, due to limited research, these might be the possible reasons: the reflective nature of Navalrai, the unique intellectual environment of Hyderabad city, where the city held Tikannas, temples, Marrhis, shrines, mosques, and churches, and Hindus and Muslims had common spiritual Gurus and Murshids. The religious practices in those times, particularly among the common people, were blurred – more inclined towards spirituality and mysticism rather than organised religious rituals. In contrast, the Brahmo Samaj encouraged the non-observance of rituals, no promotion of orthodox ideals, and no segregation based on caste, creed, or any cultural or religious identity.

Navalrai continued his Brahmo Samaj practices, but gradually he felt a need for a peaceful place where he could reflect, read or converse with his friends. In pursuit of this, he built the Brahmo Mandir in September 1875. Navalrai had acquired the land from the government, and he built the Mandir with his own resources – neither public donations were demanded nor was the government assistance sought. It was inaugurated by Satyendranath, who came to Hyderabad as the Hyderabad Session Judge. He was also a student of Keshab Sen and the son of Debendranath Tagore. He served the city from 30 August 1875 to 18 April 1876. On that day, Mr. Tagore delivered a lecture about the Brahmo Samaj, and a procession was also taken through the streets of the city.

The Brahmo Mandir had a garden, and at the centre stood a robust Banyan tree, with an elevated platform around its huge trunk. There were also some younger Banyan trees and other plants. One of the regular activities that occurred was meditation. Dayaram Gidumal, in his book Hiranand – The Soul of Sindh, has given a vivid description of the Brahmo Mandir. He writes: “There is a large square platform, besides a reservoir of fresh water, flowers, and the balmy natural peace of the beautiful environment.” He adds that on the west side of this spacious Mandir, there existed a Muslim graveyard, and the impressive mausoleum of Sarfraz Khan Kalhoro was also visible.

The Brahmo Mandir's activities were held on Sundays. In its initial days, Upasana (a religious practice or a typical meditation) was a common activity. Gradually, Udhodhana (Innovation), Aradkana (Adoration), Dhyan (Meditation), Bhajan (Singing), and Patha (Reading) became frequent activities. However, an annual event was held on the third Sunday of September.

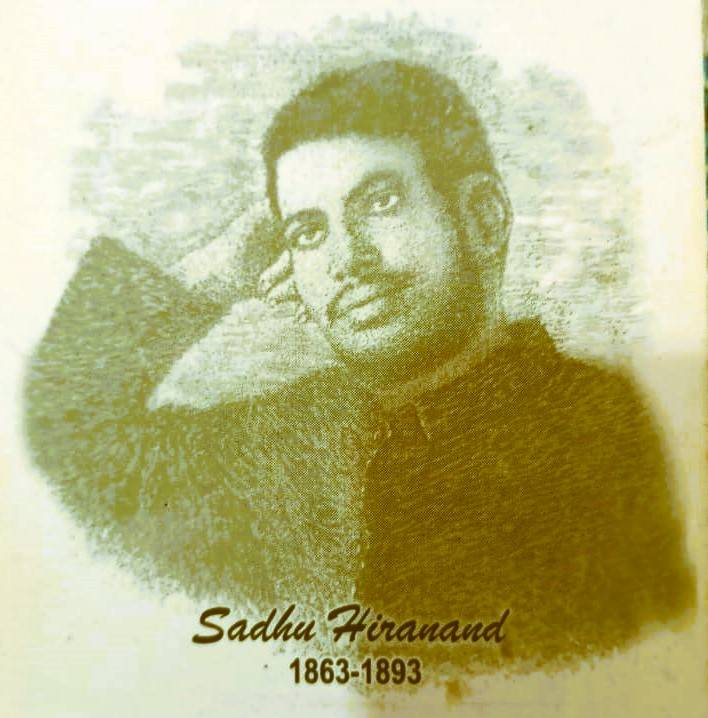

Navalrai and Sadhu Hiranad’s urns enshrined the ashes of the two noble brothers, and were buried on the western side of the garden and Samadhis were erected. Afterwards, the Mandir’s repair and maintenance were cared for by Rai Bahadur Diwan Tarachand Shaukiran, who gave Rs 8,000 for the construction of a huge hall. Likewise, Hashmatrai Lalsingh donated Rs 5,000 for the renovation of the Samadhis. On the southern side of these Samadhis, there is a layered elevation, which was the place where Sadhu Hiranand used to sit in solitude and reflect or sometimes engage with his friends to find ways to serve the people. The aims of the Brahmo Mandir were: Faith, Prayer, Purity, Love, and God.

In those days, by and large, the people of Hyderabad ignored the activities of the Brahmo Mandir. At that time, the city was roughly structured into these social brackets – Khudabadi Amils, Non-Hyderabadi Amils, Bhaibands (Khudabadi and others), non-Sindhi Hindus (Brahmins and Bhais or low-paid workers), and Sindhi Muslims.

However, an incident occurred in the family of Diwan Shaukiran, and it instantly brought the Brahmo Mandir and Navalrai into the domain of public discussion.

In December 1878, Diwan Nandiram, who had held important positions in the Talpur era and had also been the Mukhi (head) of the Amil community, passed away. According to the customs of those times, it was required that the sons and grandsons of the deceased man to shave their heads and walk barefooted with the bier to Masann, the cremation-ground. All followed the tradition, but the grandsons of the old man – Navalrai and Tarachand – refused to do so. Their refusal became the talk of the town, and the political opponents of Mukhi Shaukiran (son of the deceased Nandiram) exploited the situation in their own ways, while the orthodox religious elemens opposed him on their grounds. However, almost all of them agreed that the Brahmo Mandir was propagating the ideals of Christianity.

After the death of Navalrai and Sadhu Hiranad (1863 – 1893), the Brahmo Mandir was managed by a committee. However, some individuals also played important roles in carrying out the affairs of the Mandir, such as Diwan Kauromal Chandanmal Khilnani, Babu Nandlal Sen, Bhagat Roopchand, Diwan Pirbhdas Shaukiram, Bhai Tahlram Lelaram, Sadhu Aishwardas, Diwan Kundanmal, Dr. Nebhraj, Diwan Dhramdas Bhojraj, and Professor Nirmaldas Dramdas Gurbaxani. The professor managed the affairs of the Mandir until 1947, but the gradually changing environment in Hyderabad – the rift between its inhabitants and the communal loyalties – affected the old cultural milieu of the city, and even the British Government’s reforms and legislation left little room for the Brahmo Samaj reform agenda to flourish.

The Brahmo Samaj was a new religious movement that reached Hyderabad with the dedication and vision of a single man – Navalrai. It must be understood that the ideas of the Brahmo movement needed some structure and platforms. Therefore, in those times, some organisations were formed, all of which focused on the eradication of orthodox practices and tried to change the status of women in the society. Some of the activities revolved around the stoppage of early-age marriages, control over marriage expenditures, and the encouragement of women's education.

However, after the 1947 partition, like other plural cities, Hyderabad also changed its cultural and social milieu. First, Hyderabad’s (particularly Hirabad) wider lanes were narrowed due to encroachment, then its beautiful parks (roughly twelve parks of various sizes) vanished, temples were allowed to be occupied by migrants, and the Brahmo Mandir was erased. In the 1980s, the Samadhis of Navalrai and Sadhu Hirnand were demolished – those who had transformed the sleepy Sindh of the 1890s into a bastion of modernity. They had opened schools for girls, established welfare associations, founded clinics for the poor, provided refuge for the destitute, and disdained extravagant expenditures on social events and religious celebrations.

These noble individuals had strived to legislate marriage age and launched newspapers to educate and enlighten the populace. Now, an ugly-named Liberty Plaza and some commercial structures stand in their place.

Alas! The 1947 partition made Hyderabad a scary place. Nowadays, it has the feel of a run-down city from a bygone era: stagnant, isolated, and functioning merely as a junction. It is, in a sense, on its way to becoming a cultural backwater, a far cry from the vibrant city it once was.