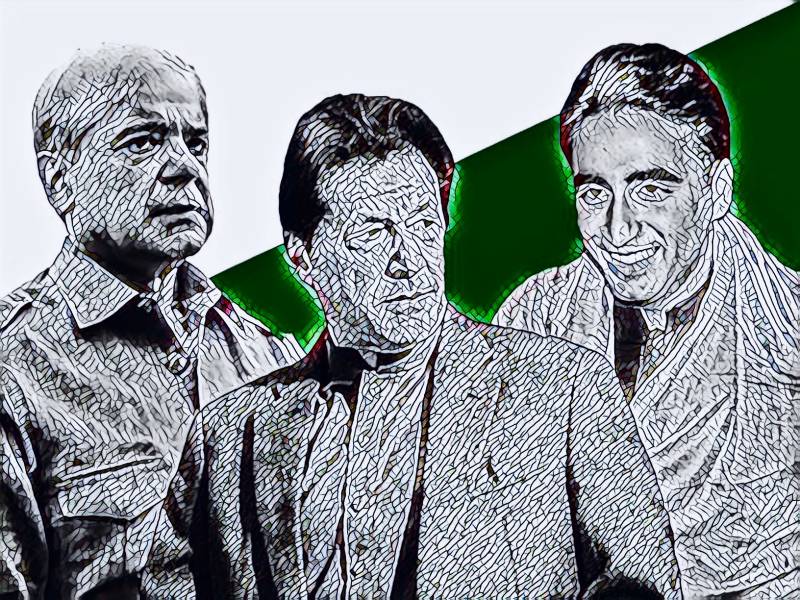

Pakistan is going through an unparalleled time in its history. It would not be wrong to suggest that while the country has seen many such scenarios, the present one does not have an arbiter of power to resolve the complex issues which the country now faces. It is important to dissect the political and legal problems while presenting some solutions.

Any functioning democracy around the world can only be successful in upholding the will of the people if all actors are ready to play by the 'rules of the game'. Whenever one of the actors decides to play outside these set rules, then anarchy prevails and the fundamentals of a democracy — constitutionalism and rule of law — are challenged.

Przeworski suggested that "democracy is a system in which parties lose elections," and the ones who lose elections must accept the results, otherwise the stability of the system is threatened. The root of Pakistan's current impasse lies in this essential principle of the process of democratisation.

By dissolving two provincial governments, Imran Khan has only deepened the political crisis. It is a win-win strategy for him; but it is a move that tests the limits of our nascent democracy. If the PTI loses the provincial elections, then it is going to blame the PDM-led government in the federal government based on its previous track record of rigging accusations. If it wins the elections, then the other parties would not trust the provincial governments under which the general elections would take place. Both scenarios offer ingredients to a recipe for further crisis, at a time when Pakistan must honour international commitments to the IMF and other lenders.

Every loser in the game pointing towards wrongdoing — real or alleged — would not strengthen the system. Rather, questioning the legitimacy of the voting process undermines its credibility and further erodes whatever trust citizens have left in the electoral process.

The political solution to such a scenario requires all political parties coming together and agreeing on the 'rules of the game' under which they would participate in the next elections. This is easier said than done: Imran Khan has roundly refused to sit with his political opponents, and the current PDM government would also not like to further capitulate its political capital by reaching out to a stubborn Khan again and again.

The legal solution lies in Article 105(3)(a) of the Constitution, under which the governor of a province must announce an election date which must not be later than ninety dates from the dissolution of the concerned provincial assembly. The ideal situation would be that the Constitution should prevail, and the Lahore high court (LHC) has already ordered the Punjab governor to announce the date of provincial elections. The LHC order remains in force.

The contrarian contention is that the mistrust between political actors must be resolved before any elections take place, and framers of the Constitution have accounted for such a scenario by inserting Article 254 which states that if any act mandated by the Constitution is not done within the stipulated time period, but is instead done later, then it would still remain valid. Under this article, a constitutional activity cannot be considered as ‘invalid’ just because it was not done within the stipulated time period.

In order to formulate an opinion which is acceptable to all, the government must send this question for legal interpretation to the Supreme Court (SC), under the apex court's Article 186 jurisdiction. The SC should rise to the occasion and create a full bench — constituted over all judges to avoid any controversy — and ensure that those who intend to play outside the set 'rules of the game' shall be penalised for not following them.

There is a cost of inaction, which seems to only be increasing as time goes by. The nation has seen recently that the president — a ceremonial figurehead — went beyond the scope of his constitutional powers to announce an election date for provinces, which infringes upon the Election Commission of Pakistan's (ECP) autonomy. The federal government might be tempted to go for an 'economic emergency' which would further complicate matters.

While the situation is far from the ideal, the judiciary or the unelected elites must not play any role in the democratic political processes. But in order to resolve this never-ending scenario, this 'bitter pill' would have to be swallowed, as no political actor can afford to lose their 'narrative' just before an impending election.

Any functioning democracy around the world can only be successful in upholding the will of the people if all actors are ready to play by the 'rules of the game'. Whenever one of the actors decides to play outside these set rules, then anarchy prevails and the fundamentals of a democracy — constitutionalism and rule of law — are challenged.

Przeworski suggested that "democracy is a system in which parties lose elections," and the ones who lose elections must accept the results, otherwise the stability of the system is threatened. The root of Pakistan's current impasse lies in this essential principle of the process of democratisation.

By dissolving two provincial governments, Imran Khan has only deepened the political crisis. It is a win-win strategy for him; but it is a move that tests the limits of our nascent democracy. If the PTI loses the provincial elections, then it is going to blame the PDM-led government in the federal government based on its previous track record of rigging accusations. If it wins the elections, then the other parties would not trust the provincial governments under which the general elections would take place. Both scenarios offer ingredients to a recipe for further crisis, at a time when Pakistan must honour international commitments to the IMF and other lenders.

Every loser in the game pointing towards wrongdoing — real or alleged — would not strengthen the system. Rather, questioning the legitimacy of the voting process undermines its credibility and further erodes whatever trust citizens have left in the electoral process.

The political solution to such a scenario requires all political parties coming together and agreeing on the 'rules of the game' under which they would participate in the next elections. This is easier said than done: Imran Khan has roundly refused to sit with his political opponents, and the current PDM government would also not like to further capitulate its political capital by reaching out to a stubborn Khan again and again.

The legal solution lies in Article 105(3)(a) of the Constitution, under which the governor of a province must announce an election date which must not be later than ninety dates from the dissolution of the concerned provincial assembly. The ideal situation would be that the Constitution should prevail, and the Lahore high court (LHC) has already ordered the Punjab governor to announce the date of provincial elections. The LHC order remains in force.

The contrarian contention is that the mistrust between political actors must be resolved before any elections take place, and framers of the Constitution have accounted for such a scenario by inserting Article 254 which states that if any act mandated by the Constitution is not done within the stipulated time period, but is instead done later, then it would still remain valid. Under this article, a constitutional activity cannot be considered as ‘invalid’ just because it was not done within the stipulated time period.

In order to formulate an opinion which is acceptable to all, the government must send this question for legal interpretation to the Supreme Court (SC), under the apex court's Article 186 jurisdiction. The SC should rise to the occasion and create a full bench — constituted over all judges to avoid any controversy — and ensure that those who intend to play outside the set 'rules of the game' shall be penalised for not following them.

There is a cost of inaction, which seems to only be increasing as time goes by. The nation has seen recently that the president — a ceremonial figurehead — went beyond the scope of his constitutional powers to announce an election date for provinces, which infringes upon the Election Commission of Pakistan's (ECP) autonomy. The federal government might be tempted to go for an 'economic emergency' which would further complicate matters.

While the situation is far from the ideal, the judiciary or the unelected elites must not play any role in the democratic political processes. But in order to resolve this never-ending scenario, this 'bitter pill' would have to be swallowed, as no political actor can afford to lose their 'narrative' just before an impending election.