The French traveller Francois Bernier visited India from 1656 to 1668, during the reign of the Mughal emperors Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, and has left behind a detailed account in his travelogue, Travels in the Mughal Empire, of the places he had visited and events he had witnessed. Many of his reflections are considered reliable, as he was a keen and astute observer. He has also recorded a detailed description of the Taj Mahal that had just been completed, documenting its construction, and building plans. It is believed that the finest building material was procured from around the world to be used for the mausoleum, built between 1631 and 1648, with an estimated cost of over 2.5 billion rupees.

The Taj showcases all the love and passion that Shah Jahan had for his favourite wife, Arjumand Bano Begum. In her excellent book, Daughters of the Sun, Ira Mukhoty, the famed Indian author, quoted Abdul Hamid Lahori, the royal biographer, “The building will be a memorial to the sky-reaching ambition of His Majesty, the emperor.” Bernier was also effusive in his praise and noted that the mausoleum of Tage Mehale is an astonishing work. This monument deserves much more praise than the pyramids of Egypt.” Bernier claimed without offering any evidence that Shah Jahan had started to build a black marble tomb for himself on the other side of the river, but the war among his sons upended his plans.

Shah Jahan moved the capital from Agra to Delhi while the Taj was still being built and, in 1647, started the construction of a new capital city, in his name, Shahjahanabad. He was so preoccupied with his new project that he visited the mausoleum of his beloved wife only once after he left Agra and before being imprisoned by Aurangzeb. During his lifetime, the Taj was already showing some signs of decay. In December 1652, Aurangzeb, while returning from a campaign, went to visit his mother’s tomb in Agra. He was distressed at the state of disrepair and flood damage he observed and, in a letter, drew his father's attention to it.

Using the flowery language of the time, as cited by Diana and Preston in their book, Taj Mahal, he wrote, “Although the buildings of these sacred precincts are as stable as they were when completed in the imperial presence. However, the roof over the blessed dome leaks on the north side during the rainy season, and the four portals, most of the second-story alcoves, and the four small domes have got damp.” The prince further added that the garden across the Yumna from the Taj, known as Mehtab Bagh, had been completely inundated by the tide. Therefore, it has lost its charm.

The Taj has been through many vicissitudes since its construction nearly three and half centuries ago. Under the British occupation of Agra, it was used for some unsavoury purposes. The mosque and the guest house were rented out to newlywed British couples for their honeymoon. The Terrace of the Mausoleum was often used for music bands playing during formal balls. Its fortunes changed, however, with the arrival of Lord Curzon, the British viceroy in India (1898–1905) who was a great admirer of India’s cultural and archaeological heritage. Curzon was singularly responsible for preserving many historic sites, especially the Taj Mahal. His love for the Mausoleum was unbounded. He had once seen a brass lamp hanging in an ancient mosque in Cairo which he liked highly. He ordered a replica to be made and the craftsman of Agra did a splendid job. Curzon donated it to the Taj, and it now hangs from the ceiling of the interior dome. In his farewell speech before leaving India he remarked with pride, “If I had never done anything else in India, I have written my name here and the letters are a living joy.”

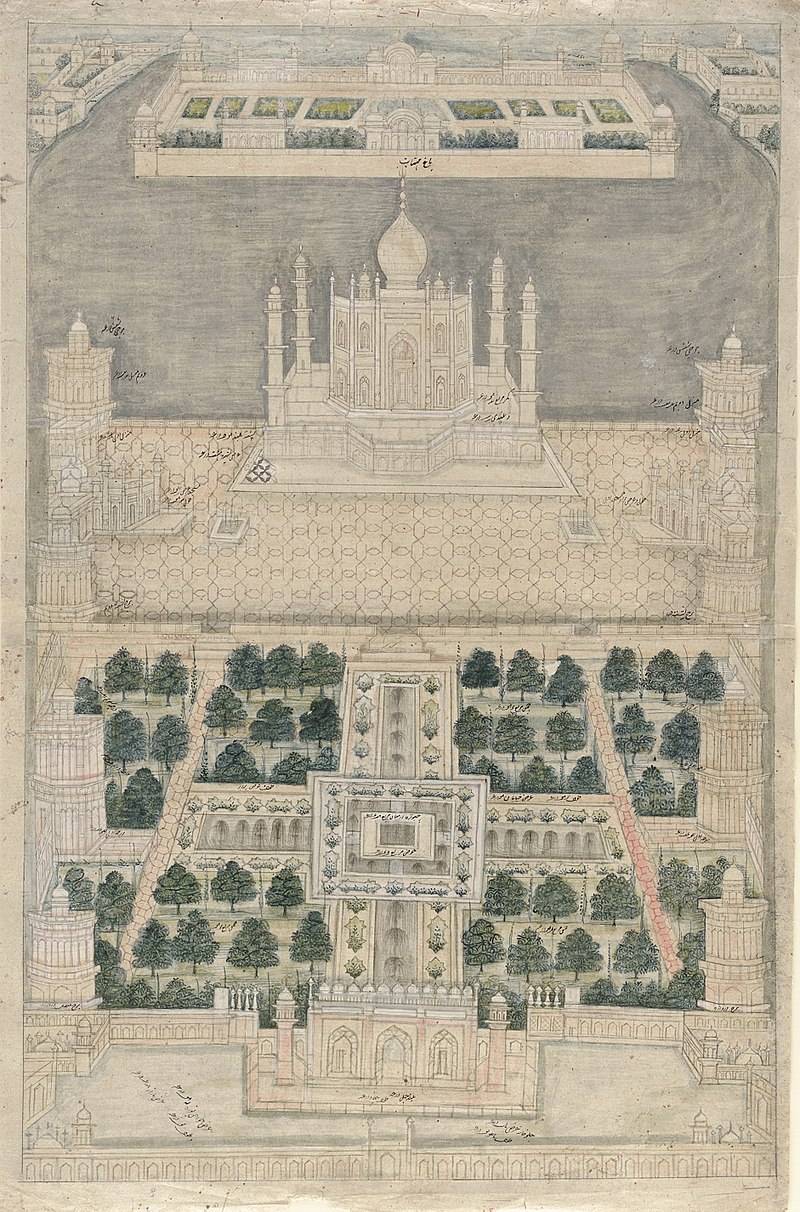

During the renovation of the Mausoleum in Lord Curzon’s time, not much attention was paid to the garden opposite the Taj and across the river, referred to as Mehtab Bagh in Aurangzeb’s letter. Most probably, it was abandoned in the seventeenth century after it suffered from frequent flooding, as we find no mention of it in contemporary literature. Fortuitously, this was to change in 1995, when the American Arthur Sackler Gallery, the National Museum of Asian Art in Washington DC, sponsored a project to study the long-forgotten Moonlight Garden. The project was part of a larger mission designed to study Agra as a world heritage site.

Two eminent scholars, Professor Elizabeth Moynihan, wife of the former US ambassador to India, and Abid Husain, a former Indian ambassador to the US were appointed as co-chairs of the project. Moynihan had already built a stellar reputation as the archaeologist-scholar who had researched gardens around Agra created by emperor Babur, the founder of the Mughal dynasty.

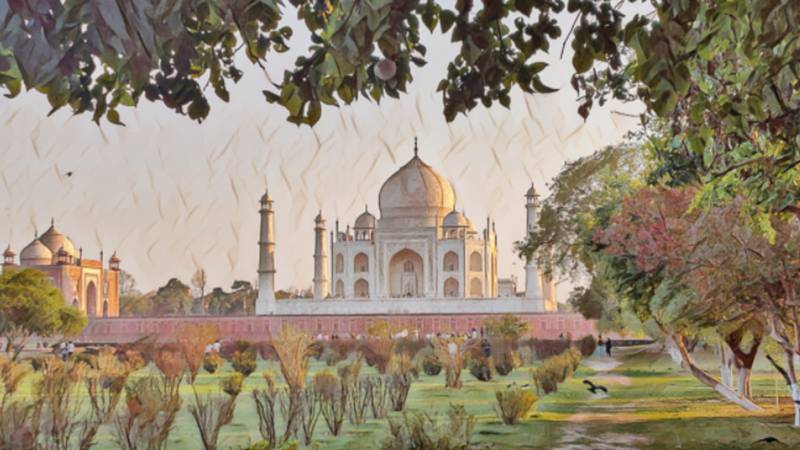

The panel members were taken to the site where the archaeological survey had initially planned to establish a tourist site. The location was remote and inaccessible. Yet the members were taken aback to find that it provided a stunning view of the Taj Mahal. Later research showed that it was the site where Shah Jahan had built his Mehtab Bagh or Moonlight Garden. The panel made some fascinating observations that were compiled in the form of a monograph in 2000, The Moonlight Garden, edited by Moynihan. The 100-page publication, embellished with beautiful miniature Mughal paintings, published by Arthur M Sackler Gallery, is now out of print. This writer was only able to borrow a copy from the US Library of Congress.

The studies by the panel indicated that during the British era, the garden ground was used as a camping site. Earlier reports from the Survey of India documented that originally there were garden pavilions and octagonal pools, but all traces of them were lost, inundated by floods, and the Garden was buried in the sand and silt of the river. In time, bricks and other precious materials from the garden were carted away by the villagers, leaving little or no trace of the garden.

In her essay, Reflections of Paradise, Moynihan argues that contrary to Tavernier’s assertion there is no evidence that Shah Jahan intended to build a second black marble tomb for himself on the opposite riverbank in the Moonlight Garden. The amount of work and craftsmanship already employed in the Taj just was not amenable to duplication. Shah Jahan always wished to be buried next to his wife and the Mahtab Bagh was intended only to serve as a pleasure garden. Moynihan speculated that positioning the Taj on its lofty setting high above the river and the position of the octagonal pools offered the optimal location to reflect the Taj’s image, especially at moonlit nights and Shah Jahan may have used the garden for quiet contemplation.

In recent years, India’s Department of Archaeology has been attempting to restore the Mehtab Bagh to its original glory. Efforts have been made to plant the trees and shrubs that belonged to the original Mughal Garden and had origin in Central Asia. The restitution and restoration of Moonlight Garden after centuries of oblivion is a testament to the painstaking research and collaboration of American and Indian archaeologists.