“Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive

But to be young was very heaven.”

― William Wordsworth, The Prelude

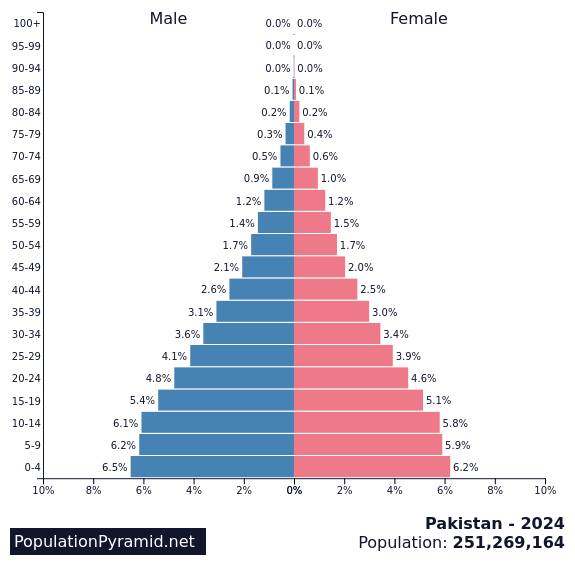

The UN's most recent World Population Prospects study, released in 2024, projects that Pakistan's population will increase rapidly from 247.5 million (around 140 million under 25) in 2023 to 511 million by 2100. Pakistan will see one of the biggest absolute population increases in the world, but with a slowly slowing growth rate, making it a demographic anomaly and a potential regional powerhouse.

Pakistan's Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of 3.61 remains significantly above the replacement rate of 2.1, making it one of the highest outside Sub-Saharan Africa. Unlike neighbouring countries—except Afghanistan—that have fertility rates at or below replacement levels, Pakistan’s TFR is not expected to drop below replacement until 2080.

Even by 2100, when it will be the third-largest youth population in the world, a staggering 165.8 million (an overall increase of 15% from 2023), it will remain among the world’s highest at 1.93. While its neighbours—and much of the world—will experience steep declines of over 60% in the under-25 populations, ushering in an era of youth scarcity, Pakistan will avoid this demographic decline.

This eccentric situation can be morphed into a potentiality known as the demographic dividend; this means economic growth potential that can result from shifts in a population’s age structure; it is characterised by a period of reduced dependency ratio (working-age population outweighs dependents) resulting in rosy economic ramifications, such as bigger gains in productivity and facilitating faster economic growth, given good education, a higher level of national savings, and investment due to a faltering dependency ratio.

Despite boasting such potentiality, Pakistan, unfortunately, has hitherto not been able to properly realise this potential; for instance, as per the Global Youth Development Index (YDI) Report (2023), Pakistan is ranked 162nd out of 183 countries, scoring 0.643 and remaining among the ten least-ranked Commonwealth countries. Similarly, in the national YDI (this assesses youth performance against four dimensions rather than the global one, which assesses against twelve dimensions), the panorama is not picturesque at all.

Why is it that we are still unable to reap the benefits we could have, and why does the future appear far from promising?

The inability to take advantage of the bulge is also evident from the spree we are facing: the burgeoning levels of crime, violence, and the radicalisation of politics and religious spheres, as well as the smuggling of humans to European countries in search of better economic opportunities.

Why is it that we are still unable to reap the benefits we could have, and why does the future appear far from promising? Well, the causations are many: inter alia, lack of comprehensive youth policies and frameworks and their implementation, low enrollment rate, pauper education quality, low labor participation, gender and class disparities, lack of political and civic engagement (except dynasty-ism), urban-rural divide, stagnant economy unable to absorb the growing employment needs, mental health issues, digital divide, etc.

Historically, the process of inking the National Youth Policy (NYP) began in 1989 and was finally approved by the federal cabinet in 2009. One can easily discern the seriousness of the incumbent governments insofar as youth is concerned. However, in 2011, it again got vaporised post-18th Amendment, and the whole function (including the decimation of the Ministry of Youth Affairs at the federal level) was devolved to provinces. Now all provinces except Balochistan have their youth policies, while the erstwhile FATA is still in the grey, as they started working on it in 2013, and given the merger post-25th Amendment, the status of youth affairs and policy directives is unclear. Similarly, Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) and Gilgit Baltistan (GB) have no formal youth policy whatsoever.

In 2020, after calibrating the power and enthusiasm and its political ramifications, PTI developed the National Youth Development Framework (NYDF), introduced in 2020, consisting of six themes, including mainstreaming marginalised youth, providing opportunities for youth employment and economic empowerment, proving meaningful civic engagement, ensuring social protection, health, and well-being, and offering youth institutional reforms.

History reveals that governments have largely remained aloof from the concerns of the youth. It was only when their potential became as undeniable as the rising sun—particularly due to their impact in the political realm—that the government began considering reforms. However, these efforts often lacked meaningful implementation.

Apart from the policy framework dilemma, our youth is bereft of quality education. There is a glaring bulge of out-of-school children (OSSC) (25.61 million as per the 2023 Population and Housing Census) currently in the country. Fueling the fire with structural and systemic idiosyncrasies in the form of different variants of education in the education sector works as a barrier to quality education, thus, jumping us into the fray of the perennial cycle of marginalisation and exclusion.

Rather than playing their part in economic, social, and political spheres, women here are mostly subject to marginalisation (forced purdah and repressing open expression of any kind) and unflinching violence and harassment.

According to the World Bank (WB), Pakistan has the second-highest rate of learning poverty, 18% higher than the South Asia regional average, and 17% higher than the average for lower-middle-income countries. Only 23% of 10-year-olds in Pakistan can read and understand an age-appropriate text. In comparison, the same metric stands at 44% in India, 42% in Bangladesh, and 85% in Sri Lanka. Without properly educated youth, how come we can reap the potential productivity gains from it?

Moreover, with a historically low investment rate of just 13.1%—the lowest in 64 years—and a consumption-driven economy, the country lacks the capacity to absorb the 0.8 million youth entering the workforce annually. This persistent structural weakness not only exacerbates unemployment but also kills the aspirations of the youth to participate in the economy, further perpetuating the cycle of poverty and inequality.

Furthermore, within these times of feminist architectonic shifts, we are on a lower end of the spectrum in gender disparity. One may wonder how our youth flourish and so our nation, without the participation of women. Rather than playing their part in economic, social, and political spheres, women here are mostly subject to marginalisation (forced purdah and repressing open expression of any kind) and unflinching violence and harassment.

Nearly 90% of harassment complaints received by the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) are filed by women, according to the Digital Rights Foundation. This abuse impedes women’s access to education, employment, and political engagement: 70% of female students report harassment, with 20% considering dropping out, while 45% of working women face online abuse, with 15% leaving their jobs as a result. Women in public office face triple the online abuse of men, with 67% contemplating leaving politics altogether.

Another important hot seat from which youth is ostracised is the political domain. Prominent families are running major parties, mostly belonging to feudal elitism. This then leads to disillusionment and a lack of hope and trust among educated youth in the political machinery of the country. Ergo, their participation is pulverised except for the youth entering politics due to the benevolence of dynastic politics. In the absence of a void in both mainstream politics and student unions due to a ban, the only niche youth then finds is in radical religious groups. This then incites violence and tensions in the state: challenging its writ.

Public investment must increase from the current 1.77% of GDP to the recommended 4.3% - 5.4% of GDP, ensuring gender-sensitive policies that provide equal opportunities for girls and boys

Conclusion

Pakistan stands at a critical juncture with its burgeoning population and youthful demographics, poised to become a regional titan. However, this potential is constrained by systemic inefficiencies, underinvestment, and the absence of cohesive policies, especially in regions like AJK, GB, and the former FATA, where weak implementation leaves large swathes of the population marginalised. Additionally, the government must devise plans to engage the over 17 million idle youth, addressing their underutilisation and preventing illegal labor migration to European countries. Furthermore, the deradicalisation of politics and religion is necessary to foster a more inclusive and stable environment for economic growth.

A robust, inclusive approach to education is critical. Public investment must increase from the current 1.77% of GDP to the recommended 4.3% - 5.4% of GDP, ensuring gender-sensitive policies that provide equal opportunities for girls and boys. Scholarships and targeted programs, particularly in STEM and business fields, can help address the pervasive gap in education and employment. Public-private partnerships should focus on improving infrastructure and teacher training while embedding curricula that foster critical thinking, STEM expertise, and civic responsibility. Furthermore, digital inclusion efforts must prioritise access for women and rural communities, ensuring that digital transformation reaches all segments of society. Mental health services must also be integrated across schools and workplaces to ensure holistic development.

Women's economic participation is crucial for national progress. Drawing lessons from countries like China and India, Pakistan must address systemic barriers that prevent women from entering and thriving in the workforce. Expanding childcare services, introducing workplace policies that promote gender equity, and offering skills training for women in high-growth sectors are essential. Empowering women economically could significantly boost Pakistan’s GDP, mirroring global estimates by UNDP that advancing gender equality could add $12 trillion to global GDP by 2025. Addressing Gender-based violence (GBV) and technology-facilitated gender-based violence (TFGBV) is equally vital to creating safe digital spaces where women can contribute without fear.

Economic policies must cater to the aspirations of a dynamic, youthful workforce. Encouraging entrepreneurship, supporting industries like IT and services, and investing in vocational training aligned with market needs will create employment opportunities. The surge in IT export services is a testament to the potential of technology in driving economic coherence and addressing the youth labor force participation in a stagnant economy. Bridging the urban-rural divide through infrastructure and economic zones will further ensure equal access to opportunities. Special economic zones (SEZs) and initiatives like the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) can play a pivotal role in fostering growth. Moreover, incubators, accelerators, seed funds, venture capitalists, and trade and business associations should play a key role in targeting youth, offering mentorship and financial support to turn entrepreneurial ideas into viable businesses.

Reviving student unions and integrating civic education into school curricula will nurture political maturity, active citizenship, and governance know-how. Lowering barriers to women's participation in governance and reserving quotas for marginalised groups can build a more inclusive political system. Engaging the diaspora for mentorship and investments can catalyse growth and foster global integration.

In short, a gender-sensitive, youth-focused strategy—backed by policy reforms and business-friendly environments—will not only harness the potential of this demographic dividend but also lay the foundation for a resilient and thriving Pakistan.