The events surrounding the Fall of Dhaka - 1971 remain shrouded in a narrative marred by omissions, lies, and silences in Pakistan. The state historiography of the three countries, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and India, appropriated this chapter of history according to their own nationalistic aspirations. As a result, any personal experience contesting the overarching official versions of history is usually censored or ignored, and any concerns raised on the veracity of the facts are also vehemently refuted as propaganda.

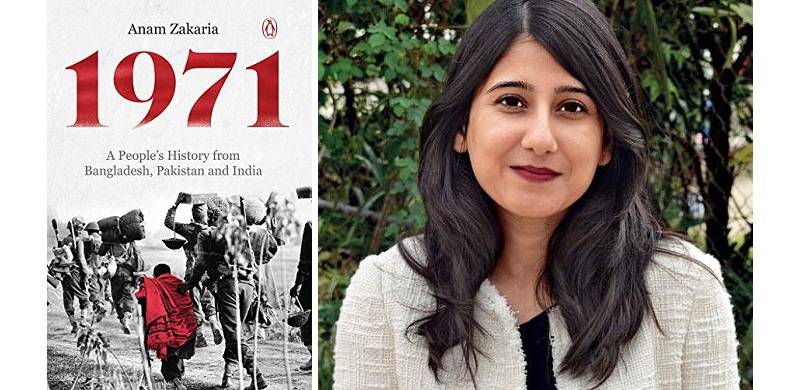

In this scenario, Anam Zakaria’s 1971: A People’s History from Bangladesh, Pakistan and India tries to present a panoramic picture of the past by narrating experiences of the individuals who lived through those troubled times of separation and violence. In addition to personal histories, the author details the institutionalisation and celebration of selective memories by the three countries through museums, textbooks, and official historiography.

Divided into four parts, the book takes you on a journey to understand one of history’s most blurred terrain. What resonates the most is the author’s sincerity in entangling the truth. Throughout the narrative, you find her struggling with the reductiveness present in popular history and lamenting how its obliteration and imposition generates flawed perceptions and prejudices.

The slowly brewing sense of marginalisation among the citizens of the then eastern wing and the ensuing actions by the West Pakistan authorities to curb the rebellion is traversed through personal memories, which allows the readers to access the chaotic years from multiple points. At times, the recollection of traumatic experiences is too overwhelming to absorb but they eventually develop into an account where the suffering and violence knew no boundaries.

The silence surrounding the 1971 war in Pakistan’s popular and official history, and its shift of blame on arch-rival India and the political cadre of East Pakistan, shatters once the language controversy, protests, state-backed operation and mass killings that are revisited through survivors’ experiences. Bangladesh’s interpretation of history holds no relevance in Pakistan’s version. Similarly, the violence perpetrated against the non-Bengalis and the awful state of the stranded Bihari community remain out of history’s boundaries in Bangladesh.

Besides negating the celebrated history, 1971 also highlights the effects of this severe appropriation on the young generation and how it is used to keep the narrative of hatred and nationalism alive. Years of misconceptions and lacunae in history only contributed to a wider abyss, thus destroying all hopes for a peaceful coexistence.

In South Asian context, this history is rare because the personal raises a question on the collective and the latter thus appears to be glaringly inaccurate. The crime of circumventing the fate and erasing the experiences of stranded communities — Bengalis in Pakistan and Biharis in Bangladesh — as they fail to fit anywhere in the projected official narrative is committed by both sides.

Zakaria successfully weaves a past that is humane, encouraging you to look beyond the statist history. The silences, the unspoken hatred, the direct anger at the injustices experienced by the citizens of Bangladesh is recorded meticulously. She observes, listens, empathises, and contemplates the partiality in history.

First published in 2019, the book is now published in Pakistan, giving readers a chance to revisit the events leading to the war of 1971 and the creation of Bangladesh through people’s histories where a sense of loss drowns all ideas of borders, ethnicity and nationalism.

In this scenario, Anam Zakaria’s 1971: A People’s History from Bangladesh, Pakistan and India tries to present a panoramic picture of the past by narrating experiences of the individuals who lived through those troubled times of separation and violence. In addition to personal histories, the author details the institutionalisation and celebration of selective memories by the three countries through museums, textbooks, and official historiography.

Divided into four parts, the book takes you on a journey to understand one of history’s most blurred terrain. What resonates the most is the author’s sincerity in entangling the truth. Throughout the narrative, you find her struggling with the reductiveness present in popular history and lamenting how its obliteration and imposition generates flawed perceptions and prejudices.

The slowly brewing sense of marginalisation among the citizens of the then eastern wing and the ensuing actions by the West Pakistan authorities to curb the rebellion is traversed through personal memories, which allows the readers to access the chaotic years from multiple points. At times, the recollection of traumatic experiences is too overwhelming to absorb but they eventually develop into an account where the suffering and violence knew no boundaries.

The silence surrounding the 1971 war in Pakistan’s popular and official history, and its shift of blame on arch-rival India and the political cadre of East Pakistan, shatters once the language controversy, protests, state-backed operation and mass killings that are revisited through survivors’ experiences. Bangladesh’s interpretation of history holds no relevance in Pakistan’s version. Similarly, the violence perpetrated against the non-Bengalis and the awful state of the stranded Bihari community remain out of history’s boundaries in Bangladesh.

Besides negating the celebrated history, 1971 also highlights the effects of this severe appropriation on the young generation and how it is used to keep the narrative of hatred and nationalism alive. Years of misconceptions and lacunae in history only contributed to a wider abyss, thus destroying all hopes for a peaceful coexistence.

In South Asian context, this history is rare because the personal raises a question on the collective and the latter thus appears to be glaringly inaccurate. The crime of circumventing the fate and erasing the experiences of stranded communities — Bengalis in Pakistan and Biharis in Bangladesh — as they fail to fit anywhere in the projected official narrative is committed by both sides.

Zakaria successfully weaves a past that is humane, encouraging you to look beyond the statist history. The silences, the unspoken hatred, the direct anger at the injustices experienced by the citizens of Bangladesh is recorded meticulously. She observes, listens, empathises, and contemplates the partiality in history.

First published in 2019, the book is now published in Pakistan, giving readers a chance to revisit the events leading to the war of 1971 and the creation of Bangladesh through people’s histories where a sense of loss drowns all ideas of borders, ethnicity and nationalism.